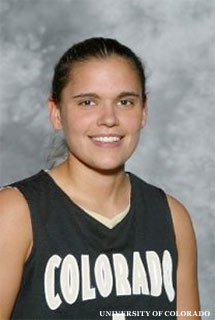

It's hard enough coming out, but playing basketball for a nationally ranked school and trying to figure out your sexual identity in the closeted and paranoid world of big-time college sports -- that’s a challenge. Kate Fagan's love for basketball and for her religious teammates at the University of Colorado was tested by the gut-wrenching realization that she could no longer ignore the feelings of otherness inside her. In trying to blend in, Kate had created a hilariously incongruous world for herself in Boulder. Her best friends were part of Colorado's Fellowship of Christian Athletes, where they ran weekly Bible studies and attended an Evangelical Free Church. For nearly a year, Kate joined them and learned all she could about Christianity -- even holding their hands as they prayed for others "living a sinful lifestyle." Each time the issue of homosexuality arose, she felt as if a neon sign appeared over her head, with a giant arrow pointed downward. During these prayer sessions, she would often keep her eyes open, looking around the circle at the closed eyelids of her friends, listening to the earnestness of their words. Here is an excerpt of her memoir, The Reappearing Act: Coming Out on a College Basketball Team Filled with Born-Again Christians.

Cass bounded out of her house before I could even put the car in park. I had arrived exactly at 7 p.m. because punctuality is the first lesson you learn when you play college sports. As I watched Cass jog to the car, her strides long and easy, an energy started to rise inside my chest. I wanted to pull the rearview mirror toward me so I could check my reflection, but I didn't want her to see me looking at myself. I ran my hand across my hair, which was pulled back, to make sure there weren’t any significant bumps. Cass pulled open the passenger’s side door and lowered herself into the seat. She was wearing jeans and a hoodie, and her hair was also pulled back, a puff of curls behind her head.

"Hey," I said, resting my hand on the gear shift.

"Hi," she said, smiling at me, temporarily breathless from the quick jog across the front lawn.

"Where to?" I slipped the car into first gear and eased us away from the curb.

"Let's go shoot baskets," she said, like she had wanted to do this very thing all along.

I turned toward her, surprised at the suggestion. "Yeah? Where?"

"Don't you know a good place?" she said, and I knew right away she meant the Coors Events Center, the 10,000-seat arena where we practiced and played our home games. I checked my keychain, which was dangling from the ignition, to make sure I still had keys to the arena, which I did.

"To the Events Center," I said, spinning the wheel so we completed a U-turn.

The entire arena was dark, and I knew, from late nights shooting by myself, that it would take a few minutes for the bulbs to slowly burn before we could see what we were doing. "This way," I said to Cass after I had flipped the switches. “The balls are back in the locker room."

The lights had just started to hum as we walked down the hallway. We couldn't see much, only the outlines of the walls, which made me so much more aware of the things I could feel. I sensed the energy of Cass behind me. And I had never been more conscious of another human's presence -- like a buzz, a radiation. I felt that if I got too close, she would be a magnet, and I would be pulled in.

We entered the locker room, and I quickly lifted two balls off the rack, which had been rolled just inside the door. I tossed one ball to Cass, tucked the other under my arm, and led us back out to the floor. Cass dribbled as we walked, finally saying, "I've been to a few games."

The overhead lights were casting a soft glow across the court, enough to see the baskets and each other. They would get brighter with each minute. As we stepped onto the wooden floor, raised two inches above the concrete, I said, "You've been to some of our games?”

Cass turned and pointed toward a corner of the arena, high up, and answered, “Me and some of the rest of us. The lesbians love women's basketball."

"Right," I said, because I knew this. I had just never allowed myself to process what it meant.

"We watch the games and discuss who on the team is gay,” Cass said.

I lifted a soft shot toward the basket and watched as it went in, dropping cleanly through the net, the bounce of the ball echoing throughout the space. I didn't know how to respond to what she had just said, didn't really know what she meant. Did she think I was gay?

So I said what I thought was the truth: "Actually, nobody on the team is gay."

She dribbled in and made a layup, adding, “Well, it is women's basketball."

We spent the next half-hour taking shots and talking about where we grew up. Cass had grown up near Chicago and gone to Missouri State on a softball scholarship. But something about the place didn’t feel right, and she loved the outdoors, so she transferred to Colorado without knowing a single person. Her family now lived in a suburb outside Dallas.

When we were done, I shut off all the lights, jogged to the locker room, put the balls on the rack, and then we walked to my Honda. Once we were both inside the car, I realized I didn't want to drop Cass off. I wanted to stay with her. "Maybe I'll take the long way back to your apartment?" I asked, looking at her and then away.

"Yes, do that," she said, and there was a lightness in her eyes.

As I was backing out of the parking spot, I swiveled my head to make sure no one was coming. Just then, I felt her hand on my neck. I tensed. I later wished I hadn't, wished I'd done something bolder and more in line with what my heart was telling me. But I froze. My shoulder blades pinched together, as if her touch was not at all what I wanted, and the air between us became thick. She left her hand there for a few minutes, then gently removed it.

"So tell me about what you believe," Cass said finally. And we kept driving, for an hour, maybe more, talking about God and life and beliefs and love. The night was black, but the moon hung high in the sky.

That ride was the first of many. On most nights, after I was done with basketball practice and she was finished with track, we would make some excuse to use my Honda, then drive through the back roads in the towns surrounding Boulder, talking and listening to CDs she had compiled, the songs becoming imprinted on my heart. Within a few weeks, although I would never admit this to Cass, I was in love with her. I know this now more than I knew it then, but during one of our rides, there was a distinct moment between us, and I can still hear her words clearly. I was letting her drive my car, and she was talking about her future, her hands gripped tightly to the wheel, like she was holding onto that very minute so it wouldn't pass so quickly. "I see myself in a city," she said. "I don't know, maybe New York, and I'm just walking down the street with the woman I love, holding hands.” I know now that I must have loved her because I wanted to be that woman, and I was hoping desperately she was picturing us.

Of course, I said nothing in the moment. I had admitted to her that I was thinking of her all the time, even while in class, and she would smile because she knew what this really meant.

I would tell her that how I felt was wonderful, and also confusing, but that I didn’t necessarily believe I was gay. I told her I was simply excited about our burgeoning friendship, as all women are when they forge a new bond. I told her I believed my attraction to her was emotional, not physical, which was a clichéd cop-out, a way of wanting someone’s time and love without committing your entire self. I imagine she recognized my mental gymnastics for what they were, the first steps of the coming-out process. And I imagine she hoped I would be strong and confident enough to plant my feet on the ground, to stop twisting away from my truth.

But my Christian teammates were perched on my shoulders, whispering, This is just agape love.

One morning, not long after the sun rose, I pulled myself out of bed and decided I needed to go running. I needed to clear my fuzzy head. I wasn't sleeping much because my mind was being eaten away by thoughts of Cass, followed by thoughts about how thinking of Cass meant something it couldn't mean. But how could love be wrong? A civil war had erupted inside my head, and my mind and body were exhausted from the conflict. Is there anything more tiring in this world than keeping yourself from loving someone? It’s like working against gravity, muscles straining, clinging to the side of a mountain.

I put on a sweatshirt and sat on the edge of my bed to tie my sneakers. The rest of the apartment was quiet; Dee and Lindsay wouldn’t be awake for another two hours. I gently closed the front door behind me. The morning was dewy, drips of water glistening at the end of green leaves. The sun was freed from the horizon, and birds were chirping, seemingly excited about the oncoming arrival of spring. The world, I noticed, seemed very sure of itself, not at all confused.

I didn't even stretch. I just started running toward the trail that connected at the back of the apartment complex. My sneakers crunched the pulverized gravel that lined the path. I breathed deeply, filling my lungs with the crisp air. All of a sudden, I decided I needed an answer: choose God or choose Cass. I ran harder, the thoughts flying through my mind as I sprinted the path, as I brushed past the leaves, as I dipped myself under extended tree branches. I turned around at the trail’s end and ran even harder on the way back. I was playing a game of roulette, and everything depended on where my mind was when I stopped running. I flew across the bridge covering the creek that led to the back of our apartment, and I crossed my imaginary finish line.

My chest was heaving. I felt alive.

I leaned down on my knees, a luxury Coach Barry did not allow us during practice because she said it would be a sign of weakness to our opponents if we did it during games. I gripped the tops of my knees and watched the sweat beads drip off my nose and form a pool in the dirt at my feet.

The decision was made. I would not be gay.

No, it was more than that: I was not gay. It seemed that simple, like choosing to turn off the light when exiting a room.

That afternoon, I called my mom between classes. I was walking past the CU library when I stopped at a common area, where many different walkways met and spilled out to the rest of the campus. There was a bench facing other benches, and I sat down. "Mom, good news," I told her, speaking into my new silver cell phone. "I'm not gay." I went on to explain how I had met this girl, she ran on the track team, and I had started contemplating that maybe I was gay. But I wasn't!

I had this conversation with the kind of bold self-assurance of someone who had made a definitive decision -- Not Gay -- and then somehow seemed to believe it was perfectly acceptable to commiserate with my mom over what a close call it had been. She sounded baffled on the other end of the line, saying things like, "What do you mean gay?” To which I responded, "Don’t even worry about it now. All is good." She must have hung up from that call and stared at her phone, confused as hell. I hadn’t been talking to my parents much because, well, what was there to say? This was unusual for us, as I typically called one of them, sometimes both, multiple times a day, just to say hi and tell them I loved them. I still loved them; I just needed every ounce of energy I possessed to get myself through each day. It felt like I was shuffling around inside of a body that I needed to inject with some kind of elixir so nobody would notice I wasn't me anymore.

That same night, I met Cass in the computer room at Dal Ward and we decided to go for a ride. I told her about my run, about the conclusion I had reached. I just wasn't gay -- isn't that exciting? She raised her eyebrows, quickly, then made her face soft again. She nodded, the motion almost imperceptible at first, then deeper and more forceful as she began to accept what I believed to be true. She let the words sink deep into her heart and absorbed them fully, so that if later I wanted to remove them, I probably couldn't. Cass had been proudly gay for years, since high school, and she had little desire to go back to being scared and confused. She was not going to live in the closet again, for me or for anyone.

The next few days, a melancholy settled over me. At basketball practice, I would run up and down the court one time and my muscles would scream at me, exhausted, depleted, like they were tearing apart. I'd fold over on myself, gasping for breath. On more than one occasion, Dee came and stood next to me in between reps, leaning in to ask, "Are you okay? Talk to me, please." But what was there to say? Tell Dee I loved a woman and I was turning myself inside out?

I was driving home after one of those brutal practices, and it was raining. I was glad for the weather, because it justified my melancholy, making the world seem sad, too. I exited off Diagonal Highway -- we lived a few miles outside Boulder -- and pulled into the gas station near the Safeway. After turning on the pump, I leaned against the car and tilted my head up toward the sky, squinting against the falling raindrops. I closed my eyes and heard the sound of a buzz, my cell phone vibrating in the cup holder. The gas tank clicked full, and I climbed back into the car.

The small LCD screen of the flip phone was bright: one new message. Not in the habit of texting, which seemed so complicated, I pulled open the phone and was surprised to see Cass was the sender. My eyes flew to the message: "Nothing worth having comes easily." I read it again and again, the rain swamping the windshield of the car, blurring the outside world.

Eventually, I closed the phone and placed it back in the cup holder. The pain started in my core, a kind of vibration, until I could feel it choking me, filling my lungs. I let out a long, soft cry -- Ahhhhhhhhhh -- like a balloon running out of air. My eyes filled with heavy tears, so now my vision inside the car matched my view through the windshield. I leaned forward until my forehead was resting on the steering wheel. Then I started to sob uncontrollably, and didn't stop until my body was empty and sore.

I probably would have stayed there longer, but a car pulled in behind me and gently beeped, flashing its lights. I started my engine and gingerly drove back to my apartment, the wipers rhythmically thudding, left-right, left-right, left-right.

-- Excerpted by permission from The Reappearing Act: Coming Out on a College Basketball Team Filled with Born-Again Christians by Kate Fagan. Copyright (c) 2014 by Kate Fagan. Published by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Kate Fagan on Twitter @katefagan3.