Editor's Note: To read the footnotes, hover your cursor over the number.

"You know," says the magician, "it's very easy to fix flipping a coin." For instance: The tosses before football games. Turns out they're totally riggable. Even with a straight coin. Con men know how. So does the magician, Richard Kaufman. He's in his 50s, has dark, curly hair, works as the editor of Genii, the nation's leading magic magazine. Specializes in card tricks. Only now, here in the sunlit kitchen of his suburban Washington, D.C. home, he's talking tumbling coins.

Heads or tails. Even odds. As indifferent as the universe itself, like the flips that sent Lew Alcindor to the Milwaukee Bucks, Bill Walton to the Portland Trail Blazers, Ralph Sampson and Hakeem Olajuwon to the Houston Rockets.

Unless ...

"See, when you flip in the air, you can get the toss location like this," Kaufman explains, losing me with a single, rapid hand flourish. "Heads side always to the left. Tails side to the right. It looks like it's spinning. But it's not. It's a true illusion."

I came here for illusions. To look right past them. To spot the sinister, hidden hand behind the not-so-random workings of the sports world. Specifically, I came to have Kaufman watch grainy, digitized footage of the 1985 NBA Draft Lottery -- the Zapruder film of athletic conspiracies -- and then tell me how commissioner David Stern managed to rig the whole damn thing.

I am not crazy.[1]

OK, sure: Maybe I've watched the '85 lottery so many times I can identify the key co-conspirators by tie color alone.[2]

Maybe I know exactly how many envelopes accounting firm partner Jack Wagner conspicuously bangs against the side of the clear plastic drawing cylinder. (One, and only one.) Maybe I've committed to memory the precise moments when Stern appears to thumb the bent corner of the winning envelope he's plucked from the cylinder, after grabbing and flipping and discarding two others. Maybe I can tell you that upon exposure to room temperature of 70 degrees, a plain manila envelope stored in a home freezer remains cold to the touch for 52.3 seconds.

None of this makes me crazy.

No, a crazy person would accept the lottery at face value. A crazy person would review the entire fortuitous chain of events[3] that produced Patrick Ewing, New York Knickerbocker, and chalk everything up to dumb luck. Coincidence, even.

A sane person doesn't believe in coincidence.

A sane person believes in causation. Connects the jumbled dots. Creates an octopus chart linking Stern to the Knicks' Dave DeBusschere to Rod Thorn to Si Green to John Thompson to Ewing.[4]

A sane person knows that if a coin flip can be fixed, then anything[5] can be fixed, that all it takes is motive and opportunity, people who can be trusted not to talk, and a public content to not ask questions, because asking questions and peeking behind the curtain and stuffing test envelopes between your ice maker and frozen fish sticks is ... crazy.

Or so they want us to believe.

Yes, a sane person forsakes the official, obligatory NBA denials and instead screens the '85 lottery with a magician, because magicians know smoke and mirrors when they see them. (A sane person thinks the 1993 Draft Lottery [6] was a bit sketchy, too.)

Kaufman peers at my laptop. We're sitting at his kitchen table, draped by a yellow-and-tan cloth. It's a lovely afternoon; outside, a flower garden blooms. Kaufman has been performing card tricks since he was 12, wrote his first magic book at 14, has written or illustrated 20 books since. He has edited and co-owned Genii for a decade, traveled around the world for magic shows and conventions. In other words: if there's a trick Kaufman hasn't seen, it probably has yet to be invented.

On the screen, a pixilated Wagner drops the supposedly secret [7] envelopes into the clear plastic cylinder. NBA head of security Jack Joyce [8] spins the cylinder, allegedly to mix the envelopes. Stern steps away from his bright blue podium and approaches the contraption.

"Look at Stern," Kaufman says. "He has to look down to unlock it. Did you see him exhale?"

Wait. Kaufman is right. Just after opening a hatch on the cylinder -- just before reaching inside to alter the course of league history -- Stern exhales, audibly and visibly, cheeks deflating like old basketballs. Why so nervous, Mr. Commissioner? Something to hide?

"That could be innocent," Kaufman says. "He's got millions of people watching. He knows the Ewing pick is big. It's easy to mistake simple tension for something more sinister." Pause the video. Stern freezes, hands on the cylinder, eyes focused downward. [9] Almost frowning. "If you had to do this, who knows, you might [soil] your pants," Kaufman adds. "If all he did was exhale in that case -- hey, he's ahead of the game."

Kaufman laughs. I don't think he believes. Not yet. He'll learn. I did.

I believe in the fix. I believe in the hidden hand, that sports have a secret, redacted history. I believe that Game 6 of the 2002 NBA Western Conference Finals was a sham, that Spygate was a cover-up of a cover-up, that Super Bowl III was preordained,[10] that Dale Earnhardt Jr.'s heartwarming 2001 victory at Daytona was, in fact, too good to be true,[11] that Michael Jordan's first baseball-playing retirement was anything but, that powerful forces don't want me to write this because powerful forces don't want you to read this. I believe that black is white, white is black,[12] the 1990 World Cup draw was rigged[13] and Sophia Loren was definitely in on the con.[14] Most of all, I believe that on June 18, 1985, inside the Starlight Room of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City,[15] in front of Pat O'Brien and nearly 150 reporters and umpteen popping flashbulbs and an entire world utterly oblivious to the conspiracy about to take place before them in plain sight, David Joel Stern did not act alone.

Of course, I might be crazy.

Hey, I didn't want to believe.

A wise man -- probably Napoleon, possibly Jon Stewart -- once said to never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence. And that's how I'd always felt about supposed sports conspiracies. The NFL rigged Super Bowl XL to punish Seattle coach Mike Holmgren for criticizing league officiating? The NBA jimmies its playoffs to favor big-market teams and bigger ratings? Please. Half the time, NBA referees can't even distinguish between one and two steps.[16] Conspiracy theorists struck me as axe-grinders, excuse makers, narcissistic alchemists spinning mundane disappointments -- missed shots, dropped touchdowns, blown calls -- into fantastical, Dan Brown-shaming narratives. They struck me as, well, crazy.

And then stuff started happening.

The FBI nailed veteran NBA referee Tim Donaghy in a high-profile gambling scandal. Donaghy accused other refs of manipulating games. The New England Patriots were busted by the NFL for secretly videotaping opponents' sideline play-calling signals. The league's subsequent internal investigation drew scrutiny from Congress. A University of Pennsylvania economist concluded that six percent of NCAA Division I men's basketball games with strong favorites likely involved point shaving.

The Beijing Olympics were tainted by accusations that members of the gold-medal-winning Chinese women's gymnastics team were underage, that the government covered the whole thing up and that the elaborate Opening Ceremonies contained Illuminati symbols. A Formula One driver crashed his own car to help a teammate win a race. On purpose. And none of this was nutty. (Um, probably the Illuminati part). There were motives. There was evidence.[17] There was there there. A rational person couldn't dismiss it.

Besides, it all seemed to dovetail with our conspiracy-minded culture at large,[18] our Obama Birthers and black helicopters (passé, yet reliably malevolent) and H1N1 vaccine hysteria, our FEMA concentration camp trailers housing Glenn Beck's salty, best-selling tears. A 2006 Scripps Howard poll found that more than a third of Americans believe the federal government either assisted in or purposely failed to prevent the 9/11 terror attacks; a 1999 Gallup poll found that six percent of Americans think the moon landings were faked. In both cases, plot proponents are almost certainly wrong. But in a world where both the Tuskegee syphilis experiments and Watergate actually happened, are people wrong to be suspicious?

Maybe conspiracy theorists were right. Maybe the sports world was akin to pro wrestling, a series of ersatz outcomes staged and manipulated by a hidden, controlling hand. Only whom did the hand belong to? What did it want? How did it remain hidden? How would it react when exposed? Also: Did Ewing really land in Gotham fair and square?

Dubious but intrigued, I took it upon myself to find out.

Understand: The standard journalism thing wasn't going to work.

A few years ago, I brought up the '85 draft lottery with then-NBA deputy commissioner Russ Granik. Conversational mid-air collision. Granik argued that if the league was actually corrupt, then large-market teams would always win the lottery.[19] Then he sighed, like a man on hold with customer service.

Of course, how else would Granik react? By confessing? A line from the Mel Gibson movie "Conspiracy Theory" applies: "A good conspiracy is unprovable. I mean, if you can prove it, it means they screwed up somewhere along the line." And that was my initial hurdle. I couldn't make house calls on alleged conspirators like Stern, hidden cameras and "Dateline"-style ambush questions in tow. The plots were too deep, the omerta too strong. The hidden hand wasn't about to answer the door and invite me in for tea.

I needed outsiders. People with lots to tell and little to lose.

I started with Doug Christie, who played for Sacramento in Game 6 of the 2002 Western Conference Finals, a contest that stands as the 7 World Trade Center of league conspiracy theories. For the uninitiated: the Los Angeles Lakers defeated the Kings in spectacularly dubious fashion, shooting 27 fourth-quarter free throws to the Kings' nine and benefiting from a number of questionable calls, all of which prompted fan outrage and an official letter of protest from legendary consumer advocate Ralph Nader. In a 2008 federal court filing, Donaghy alleged that Game 6 was manipulated on league orders by two "company men" referees to produce a Lakers victory, ensuring a ratings-juicing, profit-producing Game 7.

Shortly thereafter, Christie posted the following on his MVN.com blog:

Christie goes on to mention blackballing, having his career taken away from him with "lies and propaganda, just as that [playoff] series was." Sounds conspiratorial. I place a call. Through a representative, Christie agrees to meet at his Seattle-area home. We will watch Game 6 together.

One snag: I can't find the game. Anywhere. Neither can Christie. Odd. The owner of the basketball website 82Games.com offers to help out. He says he'll send a DVD copy of the contest via airmail.

I wait. And wait. All the way until the afternoon before I'm supposed to board a jet for Seattle.

The disc never shows.

No game, no interview. I have to cancel. Less than a week later, I hear from the front desk of my condo building. Is this your package? The disc. It was "misplaced." I try to reschedule. Sorry, says the rep. Christie is attempting a pro comeback, can't afford to antagonize the wrong people. Please understand. I mumble something affirmative, distracted. Why this package? Why now? Could this be the hidden hand?

It's probably a coincidence.

Next comes a skeptic. A man of numbers and facts. Elliott Kalb. Nicknamed "Mr. Stats." Works as a researcher and statistician for NBC Sports. Wrote a book called "The 25 Greatest Sports Conspiracies of All Time." Bears a passing resemblance to a dark-haired Stern. (That last part freaks me out just a little.)

It's summer. About two months before the Beijing Olympics, where Kalb will cover baseball. We're sitting in a Metropark, New Jersey, sports bar, surrounded by team memorabilia and close-captioned flat screens turned to ESPN News. The sickly sweet smell of jalapeño poppers hangs in the air, deep-fried and oppressive. Picking at an uninspired Asian salad, while Kalb sips a diet cola, I bring up the '85 draft lottery.

"Skepticism is reasonable," Kalb says. "I'm not saying David Stern did anything in 1985. But just the appearance of things leads people to ask questions. People should ask questions."

Hold up. I asked Kalb here to talk conspiracies. To place them under the heat lamp of empirical analysis, wilting them one by one. In fact, that's what I was counting on. Because I still regarded Stern as innocent, and Christie as slightly kooky, and people who think the 2006 World Cup draw was rigged[20] as downright batty.

Only Kalb isn't playing along. Nope, he's making me feel naïve, like I'm the whack job. Our conversation moves to Donaghy. The whole thing reeks, he says. Think through the early timeline. In June of 2007, the FBI contacts the NBA about a referee it believes is betting on games. Two weeks later, Donaghy resigns; a mere two weeks after that, Stern publicly proclaims that Donaghy is a "rogue, isolated criminal."

In essence: Move along. Nothing else to see. No other shooters on the grassy knoll.

"That's the thing that gets me," Kalb says. "How do you know that until you investigate? And even if you investigate, how would you know for sure?

"Look, something like Super Bowl III, it's retarded to think that you can get to a whole team of players and keep things quiet.[21] But can you get to tennis players,[22] boxers,[23] a jockey,[24] a race car driver? It's more likely. I think it's unbelievable that there hasn't been more proven against umpires, referees and officials.[25] In all of these major sports."

Like the big-time broadcasters he works for -- Cris Collinsworth, Bob Costas -- Kalb travels extensively. He has been to every major league city. He was courtside for Game 6 of the 2002 Western Conference Finals. Everywhere he goes, fans say the same thing. The games are rigged. The con is on. The chatter led Kalb to write his book. The book led him to an undeniable conclusion: Historically speaking, there has been a hidden hand.

In fact, it's not even hidden. An unwritten agreement kept baseball segregated until Jackie Robinson's 1947 debut. An informal racial quota system governed pro basketball in the 1950s. MLB owners conspired to hold down free agent salaries in the mid-1980s. The head of the NHL player's association conspired with league owners to retard salaries as recently as 1991. These are facts. They are not in dispute. And if Salt Lake City could secure an Olympic bid through bribes,[26] then why wouldn't China agree to secretly support Jacques Rogge's bid to head the IOC in exchange for Europe's backing for Beijing's bid?[27] If big league owners conspired to hose Tim Raines,[28] then why wouldn't they conspire to screw Barry Bonds, whose agent says is the victim of blackballing?

Skepticism is reasonable.

"When I was looking back at collusion, it was like, wait a minute -- Tim Raines was the best player in the NL, and he couldn't get a contract!" Kalb says. "Or look at segregation, where the newspapers were in on the conspiracy. We need reminders of this. There's always an incentive to cheat."

Kalb has to run. Says he's working on a golf book, and also penning an update to his conspiracy tome: the 30 greatest sports conspiracies of all time.[29] I notice he's wearing a polo shirt featuring a Super Bowl XL logo, a game some people[30] maintain was rigged.

"That's exactly what I mean," Kalb says, laughing. "When things are too good to be true, we want to know why."

What the world saw in a Beijing pool: All-American Golden Boy Michael Phelps, arms churning, torso undulating, legs kicking, cutting through the water, chasing a record-tying seventh gold medal in a single Games, chasing Serbia's Milorad Cavic in the finals of the 100-meter butterfly, still churning, still kicking, still trailing, arms shooting toward the wall, appearing to lose the race and ... winning! I-don't-fathom-what-I-just-saw winning! Winning by the smallest unit of measurement in swimming, a single hundredth of a second, 50.58 to 50.59, now pounding the water, and howling, howling for a victory that was recorded and confirmed by not one but two Omega timekeeping systems, yet defied rational explanation, because sometimes you just have to believe[31] in magic.[32]

What Max saw: A big fat lie, too good to be true, perpetrated and disseminated by a cabal of corporate overlords on holiday from sparking WTO protests.

I met Max online. I think that's his name. Only he might be a she. And he/she might be more than one person.[33] Max had picture, facts, questions, all layered like nesting dolls. He had a website, 001ofasecond.com, alleging a global Summer Olympics fix, posing a single, pressing query: Michael Phelps -- the Greatest Amphibian of All-Time, or just another corporate-owned Frankenstein?

Nah. No chance. I could accept Kalb's argument: The hidden hand was once real. Race quotas and salary collusion actually happened. But for dark forces to still be scheming behind the curtain, rigging live Olympic swim races before millions of transfixed viewers? That was too much, a theory too far.

On the other hand, Phelps' victory did seem a bit too good to be true. And I wanted to know why. So I contacted Max, asked if we could correspond.

From: conspiracy@001ofasecond.com

To: Patrick Hruby

Sure, although I don't know what there is to discuss when everybody saw that the other guy won.

Omega, Max says. Start there. Consumer watchmaker. Official timekeeper of the Beijing Games. Responsible for the underwater touch pads that concluded Cavic lost. Also Phelps' sponsor. Obvious conflict of interest. Phelps needs Omega to make money. Omega needs Phelps to succeed to make money.

Hard to argue.

Next, the photos. Omega has digital pictures, taken from above the pool, supposedly proving that Phelps won. Only the watchmaker won't make the snapshots public. Why? And why isn't FINA, swimming's governing body, pushing harder for a prompt release? Suspicious, Max says. Smells like a cover-up.

Hard to argue.

Then there's NBC, Max adds. Phelps is their unofficial Olympic mascot; his quest to top Mark Spitz's record seven gold medals is the ratings-juicing narrative of the Games. The Peacock has influence, pays enormous sums to televise the Olympics. Is it in NBC's interest to see Phelps fail? And what about FINA? What's better for the sport -- Phelps' historic individual accomplishment, or some Serbian guy touching the wall first? If Phelps wins, everyone wins; if Cavic wins, he remains some Serbian guy.

Hard to argue with that either.

Everything fits. Is Max onto something? Is this the hidden hand? I have to wonder. Six days after the race, Omega releases the photos. I forward them to Max. I'm relieved. So much for the fix, right?

From: conspiracy@001ofasecond.com

To: Patrick Hruby

Wow! If this wasn't for real, it would've been dismissed as a bad joke ... they look more like some tiny abstract impressionist paintings than the hi-def evidence needed. It is utterly ridiculous that Omega claims this as 'evidence'. By doing so they only validate the theory that something funky happened in the Water Cube that day.

Moreover, it is interesting to note how they waited one full week before releasing these ridiculous images ... Are they just trying to enter their brand into the conversation again? ... We are asking for a high-def, high-speed underwater video that apparently FINA has in their possession, but refuses to release. We want clear visual evidence from FINA, not blurry, tiny photos from the watchmaker Omega ...

Yet again, it's hard to argue. The photos are totally inconclusive. And the harder I look, the more I'm perplexed. Distrustful. Of everything. Reuters reports that Omega has a commercial contract with NBC to provide visual services during Olympic swimming races. Connect the dots. Sports Illustrated releases a second, clearer set of photos that appear to indicate a Phelps victory; on the other hand, the magazine also puts Phelps on its cover for two straight weeks. Follow the money.[34]

FINA honcho Cornel Marculescu attempts to squelch doubt by stating that Phelps won because he touched Omega's sensor pads fist, and that "the touch stops the clock." Only that isn't exactly true: Touch pads are activated by a minimum amount of force, and FINA officials don't even seem to know what that is.[35]

What to believe? Who to believe?

I read another article, this one detailing how NBC Sports chairman Dick Ebersol had the IOC move swimming and gymnastics to Chinese morning hours to showcase both sports in American prime time. Before finalizing the shift, however, he ran it past one man: Phelps.

Why? Because Ebersol didn't want anything to harm Phelps' performance. Because the two reportedly have a close relationship,[36] Because everything in life[37] is based on relationships,[38] on handshakes, and sometimes those handshakes are ... hidden.

I forward the article to Max. He -- she? they? -- promises to incorporate the information. And seems inordinately pleased.

Freeze it. Right there. The 5:28 mark. The video is blurry. The gesture is crystal clear. Stern reaches into the tumbler, grabs three envelopes, holds them for a split-second -- just long enough to determine which one is frozen ...

Look, I'm not crazy. Just curious, watching the '85 draft on YouTube, checking out the user comments below:

FIXED

Sad situation. Even sadder when Stern won't admit it

I don't usually believe in conspiracies, but ...

This is so stupid. There is no way this was fixed unless David Stern is a magician

"Every time this video gets hosted on a site somewhere, I'll get like 500 people writing me messages," says the voice on the phone. "It can be ridiculous. I never thought this would be such a big thing."

The voice belongs to Tyler Johnson. He's 20-something, lives in New Hampshire, works in a factory. Spent his childhood weekends at his father's apartment, watching basketball tapes, because dad's television only got two channels. Johnson has probably seen the '85 draft 500 times. He posted the footage on YouTube for fun. He never expected it to garner nearly 400,000 views, a number that strikes me as crazy.

Does Johnson believe? He tries to be objective. But he leans toward a fix. Mostly because the plot involves New York. The Knicks always benefit from suspicious circumstances: the flagrant foul called against Indiana's Reggie Miller in Game 7 of the 1994 Eastern Conference Finals ... Allan Houston's three-step game-winning shot in 1999 ... Larry Johnson's phantom four-point play in the same postseason ...

"I mean, if you think about the '85 draft, it makes sense," Johnson says. "All the teams going up against New York were small markets. You have a clear drum, it's easier to rig …"

Wait. Hold up. What difference would a clear drum make? Why would Stern need to see a frozen envelope?

"Because most people don't think it's the frozen envelope. Most people think it's the bent envelope."

The bent envelope?

"Yeah. Either slammed against the container, or pre-bent."

Here's the thing about redacted FBI files: The agency doesn't black out incriminating text. Not anymore. They leave it blank. Little white voids. It's easier that way. Nothing covered up. I know this because Brian Tuohy is currently rifling through a stack of white envelopes with government return addresses labels, pulling out actual bureau documents, documents he personally obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. "I got one where the entire report was redacted," he says. "Five blank pages. Take a look."

I do. Empty pages with black box borders, like picture frames.

"Since 1963, the FBI has had a sports bribery designation in its files," Tuohy continues. "They terminated it in the 1990s, rolled it into six other designations, like mafia stuff. But in those 30 years they created some 450 files. That's, like, one file a month!"

Tuohy hands me a sheet of paper. It references a memorandum from San Francisco, dated June 1990. SPORTS BRIBERY -- INTERSTATE TRANSPORTATION TO AID RACKETEERING. He offers another sheet, this one labeled 172C-95:

It should be noted during interview that ______ provided bureau agents with ______ prior to bureau focusing on that aspect of this investigation. Additionally, ______

The next paragraph is blank.

In addition, he advises that _____

Another blank paragraph.

Advised that he _____

Another blank paragraph.

Ausa Ty Cobb,[39] United States Attorney's Office, Baltimore.

"Horse racing, college sports, pro," Tuohy says. "I've put in 40 requests. I've gotten 10 back. Have you seen Wilt Chamberlain's file?"

Um, no.

"There's a Celtics player in there, a name that shows up more than once. Forty years later, it's still redacted. It's like, who are you protecting?"

Tuohy is not crazy. I mean, sure: maybe he's working on a 264-page manuscript arguing that the entire sports world is fixed.[40] Maybe he talks about attending an upcoming Chicago sports card show not to get Joe Namath's autograph, but to ask the former Jets quarterback if Super Bowl III was rigged. Maybe he has an email address with a fake name -- Dustin Elliot[41] -- in case NFL Security comes looking for him. Maybe he has an office bookshelf containing tomes like "The 9/11 Conspiracy" and "Witness to Roswell." Maybe he sometimes says things like, "Yeah, I think we went to the moon, but I can see some of the other side's points."[42] And maybe he's a self-proclaimed "sports conspiraciologist," the top such figure in the country.[43]

Still, none of that makes Tuohy crazy. For one, I'm the guy who wanted to meet with the country's top sports conspiraciologist -- so what would that make me? Besides, for a man who collects FBI files, Tuohy seems normal. Boring, even. He is in his mid-30s. He works at a music store, giving guitar lessons. He's married to a nurse. Tuohy has a wide smile and close-cropped brown hair; he's wearing shorts and a T-shirt and petting his black cat. Unfailingly polite, he speaks with the Midwest accent of an extra from "Fargo," comes off as unthreatening as a three-legged golden retriever. We're sitting in the living room of his Kenosha, Wisconsin, home, feet ensconced in soft, plush carpet, just a couple of regular Joes talking Brett Favre and watching ESPN.

That is, until a commercial mentions the 1958 NFL Championship game between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants. As Tuohy reclines on his couch, a voice drifts from the television: "Yankee Stadium ... Johnny U. versus the Giants ... the greatest game ever played ..."

"There's the fixed game," Tuohy says, matter-of-factly. "The one with the million-dollar bet."[44]

"Interesting theory," I say.

Tuohy takes exception. The word " theory." It's dismissive. A way to avoid hard questions. Special Relativity is a theory. Science uses theories every day. Ninety-five percent of Tuohy's as-yet-unpublished manuscript is fact. He's just going the extra step, putting a foot toward understanding. Anyway, facts aren't essential. Forget the smoking gun, he says. Look for motive. "It's like that scene in 'JFK,' where Kevin Costner meets Donald Sutherland,"[45] Tuohy adds. "Who shot Kennedy from what building doesn't matter. What matters is: Why was he shot? Who stands to gain?"

Sports aren't about on-field competition, he explains. They're about making money. Money means corruption. 1950s television quiz shows were scripted. Reality TV is scripted. Network news automotive crash tests are scripted. Why would sports be any different? Tuohy notes that there's a difference between individuals manipulating contests for gambling purposes (illegal) and leagues manipulating contests for better ratings and storylines (legal, just like in pro wrestling). He doesn't want to sound paranoid. It's just the nature of the game. Everyone does it. "If you're having a garage sale, and someone asks, 'does this work?'" Tuohy says. "You say, 'yeah, it works.'

"I just don't want to be lied to anymore."

I bring up Michael Jordan. Tuohy doesn't believe that Jordan retired in 1993 at the peak of his professional basketball powers because he wanted to chase curveballs for Class-AA Birmingham. Tuohy believes that Jordan left because Stern secretly made him leave, because the NBA knew about Jordan's gambling habit and wanted to squelch a potentially ugly scandal. The hidden hand as fist.

Tuohy wrote as much in an article published on Disinfo.com,[46] connecting the dots from Jordan's gambling debt to convicted cocaine dealer James "Slim" Bouler … to San Diego businessman Richard Esquinas claiming in a book that Jordan owed him $1.25 million from golf wagers ... to reports that Jordan enjoyed an all-night Atlantic City gambling binge during a playoff series against the New York Knicks ... to Esquinas telling league investigators that he overheard Jordan mention a point spread during a telephone conversation with an unknown person ... to Jordan claiming he retired to spend time with his family, only to play minor league baseball ... to Jordan saying that he would return to pro basketball "if David Stern will have me" ... to other things Tuohy knows but can't print because they could get him in serious trouble.

"That other stuff's hearsay," he says.

I ask him to share. He does. He's right. It's hearsay.[47] It sounds crazy. But also ... sorta plausible. Unless I'm crazy. Anyway, we're talking about the Internet. Tuohy has an alias. Why not print what he thinks he knows, then see what happens?

"Nah," he says. "You don't want to mess around with heavyweights.[48] I half expected you to show up with Rocco and Biff and quiet me down, put me in some cement shoes and throw me into Lake Michigan."

So you've been threatened before?

"I don't think anyone wants to threaten me," Tuohy says. "Because that would just push me into the limelight."

He sounds almost sad.

Like Tuohy, Mr. X doesn't want to be lied to. He works for the federal government, as a staff attorney for _____. On a hot summer day in the nation's capital, we meet in the subterranean, climate-controlled _____ cafeteria. I bring my laptop. Mr. X brings a large, accordion-style file folder containing investigative charts and notes.

The topic? SpyGate.[49]

"The _____ all kind of stonewalled," he says. On _____'s behalf, Mr. X tried to scale the wall. Get to the truth. He reviewed news reports and press conference transcripts. He personally left telephone messages with the _____: director of football research _____, video assistant ____, video director_____. Minutes later, a lawyer called back. No dice. No one would speak. "That's not common," Mr. X says. "When people have nothing to hide, they don't mind talking." Mr. X was in the room when _____ questioned former team employee _____; he was on hand for interviews of NFL executives ____ and _____. (The former "stuck to his talking points"; the latter was "all over the place"). Mr. X reached out to other _____ sources, like _____ team security director _____ and former _____ player _____. Most declined to respond. Unanswered questions linger.

Mr. X talks. For a long time. I listen. And type. Because I don't believe the league's official explanation of events. Because Kalb was reasonable, and Max made sense, and even Tuohy wasn't too far out there. Because I just want the truth. And wanting the truth does not make me crazy.

Finally, after spelling out every detail of the conspiracy -- the plot, the players, the cover-up, the unresolved issues -- Mr. X hands me a printout, a complete chronology of events. He looks at the notes on my screen. "Off the record," he says. Our whole conversation. No names. No attribution. I nod. Rules of the game. I don't want to be lied to. Technically, I haven't been. And now I understand.

This is how the hidden hand stays hidden.

The file is large. Almost 100 MB, high quality, better than YouTube. The '85 draft lottery, start to finish. I asked Johnson to send it. To see for myself. To fit the facts with the motive. I'm downloading now, watching as I download, messaging with Johnson:

Me: 40% done. Jack Wagner looks like a movie villain

Johnson: he does seem to emanate shadiness

Me: like he knows something is up

Johnson: at 5:21 Wagner slams the fourth envelope into the drum

Me: He does

Me: But not the others

Johnson: exactly

Johnson: the slam bends the corner

Me: I see

Johnson: as far as body language goes on Stern you can see much better that he appears to be watching the drum out of the corner of his eye the entire time the drum spins

Me: Strange

Johnson: yeah very suspect

Me: 60%

Me: plus the deep breath Stern takes

Me: and the grabbing of three envelopes

Me: then flipping them over and taking the bottom one

Me: why not grab just one?

Johnson: Stern definitely made a concerted effort to go for that bent envelope, it seems like he had his eye on it the entire time

Johnson: maybe the big sigh is because he sees it is covered and he has to make an odd grab

Me: true

Johnson: you can see Stern flicking the bent corner several times at 6:03

Me: hold on

Me: I have to reopen the movie

Me: HOLY CRAP

Johnson: isn't that something?

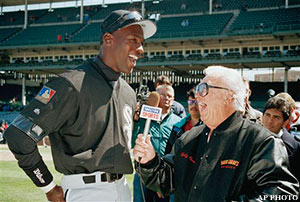

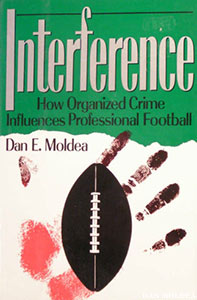

Dan Moldea wrote a book on Jimmy Hoffa, becoming the first reporter to link the former Teamsters president and two mobsters to the JFK assassination.[50] Nothing happened. No death threats. No cement shoes. He wrote another book detailing Ronald Regan's mafia ties. Again, nada. No blowback. Favorable reviews.

He then wrote a book connecting the NFL and organized crime, 1988's "Interference."

"That book," Moldea says, "ended my career."

Moldea may be exaggerating. Or not. He digs into an omelet, tomatoes on the side. We're sitting in a Washington, D.C. diner, an inconspicuous spot near American University, a few miles north of the mailbox where convicted spy and former CIA agent Aldrich Ames once left chalk marks to request meetings with his KGB handlers.

Moldea is definitely not crazy. Quite the contrary. Wearing a black polo shirt under a gray suit jacket, he looks like what he is: an old school investigative journalist. He prefers documents and interviews to speculation and intuition. Two of his other books -- one on the RFK assassination, the other on the death of former White House attorney Vince Foster -- disprove longstanding conspiracy theories. He is seasoned and smart, stubborn and unafraid.

He says he should have known better than to pen "Interference."

Moldea's father, Emil, warned him. From his deathbed. A former Ohio State football player and roommate of pro Hall of Famer Dante Lavelli, Emil tried to shoot down the idea just hours before losing his battle with pancreatic cancer. "Don't write that goddamn book," the 64-year-old told his son. "It will break your heart."

"He knew raw power would come at me," Moldea says. "Like a rifle shot."

Moldea wrote "Interference" anyway. The contents were explosive. No fewer than 26 past and then-present NFL team owners with documented personal and/or business ties to members of the gambling community and/or organized crime.[51] No fewer than 50 legitimate investigations of league corruption either suppressed or killed due to a sweetheart relationship[52] between NFL Security[53] and law enforcement.

Moldea confirmed that Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom really did bet on his own team in the 1958 NFL championship game, taking the points and wagering $1 million.[54] He found that Rosenbloom likely gambled another million on his club to win Super Bowl III. He corroborated evidence -- originally obtained via separate IRS and FBI investigations -- suggesting that two league referees helped fix no fewer than eight NFL games.[55] In Las Vegas, Moldea met with bookie Don Dawson, who admitted he personally conspired with NFL players in at least 32 games that had points shaved or were dumped outright.

"I didn't put [everything I had] in the book because I didn't want lawsuits," he says. "Dawson talked a lot about [former NFL quarterback] Bobby Layne. I wrote fairly mild stuff about Layne. I got a call one night from a guy who identified himself as Layne's son. He said he hired a hit man to come kill me."

Looking back, Moldea says he was naïve. He knew the NFL would attack him. But he figured there were honest people he could trust, like then-NFL Security head Warren Welsh.[56] Moldea began his book tour at Las Vegas' Stardust Hotel. He says he invited Welsh to his room, laid out his Dawson tapes and documents, went downstairs to give an interview. He returned to find Welsh shaking his head. "Jesus Christ, Dan. You just made my job so difficult."

The two men went to the lobby. Welsh hailed a cab to the airport. Before getting in, he turned to Moldea. "He says to me -- and I'll never forget this -- 'Dan, we gotta destroy you now,'" Moldea says.

Next came the bullets. Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell called Moldea a "sick muckraker." The league dismissed "Interference" as tabloid journalism, a collection of half-truths, rumors and distortions.[57]

The most damaging attack came from a New York Times book review, penned by veteran NFL beat writer Gerald Eskenazi. Eskenazi[58] accused Moldea of "sloppy journalism," a career death blow at the time;[59] Moldea responded by pointing out factual errors in Eskenazi's review and demanding a retraction. The paper stood by the article. Moldea sued for libel, claiming Eskenazi's opinion was based on provably false facts. The case became a five-year ordeal, a First Amendment flashpoint that nearly reached the Supreme Court,[60] with almost every major national media organization lined up against Moldea -- in theory, to protect free speech -- and a U.S. Court of appeals ruling for Moldea before reversing its own decision.

"I wanted to fight the NFL," he says. "Instead, I went to war with the New York Times. They ran interference[61] for the league. Usually, people cheer for David. No one was cheering for me."

Things got worse. And more suspicious. Moldea discovered that Sandy Smith -- a Washington Post book reviewer who had slammed "Interference" -- was in the middle of a lawsuit against Moldea's publisher. Representing Smith? Bill Hundley, a former chief of NFL Security. The 1992 book "Alien Ink" detailed a covert FBI program that "reviewed" -- read: sabotaged -- authors and their published works. "Interference" was among the targets. In 1996, Moldea filed a FOIA request; resulting documents revealed that the FBI placed him under investigation just days after his book's release and that the special agent heading the inquiry was Mitt Ahlerich, a man who later became head of NFL Security.

"When you get involved in something like this, your worst fear is that you run up to people in the street and grab them by the lapels and want to explain your half of the story," Moldea says. "I didn't get quite that bad. But it was close."

Moldea can live with paranoia. Every investigative reporter, he says, believes there is some force out there screwing with his or her life.[62]

What still bugs him about "Interference" is this: During his 13-city book tour, he brought his tapes and notes to every stop. Ready to open up. Lay things out. Only no one asked to see his evidence, pick up the baton, investigate further.

Moldea mentions another court case, this one involving the NFL and game-fixing. Says he testified as an expert witness, along with key law enforcement people.[63] Says the case was ultimately settled, and sealed, and that the depositions would give me a full-on heart attack ... but if I really want to see them, he just might be able to help me. "Play this wrong, and it's a quick way to destroy your career," he adds. "You're talking to a cautionary tale here. I'm not kidding around. This is dangerous [expletive]."

The FBI. The NFL. The media. The courts. The hidden hand writ large. Do I want to take them on? Am I crazy? Moldea thumbs his cellphone. He offers to help.

"I have an up-to-date number for Warren Welsh. I think he might be ready to talk. If you want Warren's number, call me."

I force a brave smile. But I know I never will.

Was I cracking up?

In too deep?

Had I heard too much?

The world was closing in. I reach out to Christie, one last time. I want him to show me the hidden hand. Expose them. We arrange a meeting in Los Angeles. The day before I'm supposed to depart, his business manager calls. A new manger, one I've never spoken with before. Meeting's off, she says. Doug wants to work in television. Can't afford to be seen as controversial.

I understand. They make the rules. And they got to him.

I go to a Washington radio station. Sit in on a sports talk show. I need to hear from the callers. People like me. Uncorrupted. Unafraid. The hosts are friendly. Generous. They promise to open the phone lines, talk sports conspiracies.

A segment passes. The hosts debate the weather. They debate squat-only Chinese toilets. Next comes the news. An update guy mentions that the NFL Players' Association spent $12,000 on paper shredding last year, destroying roughly 62 tons of documents. Sixty-two tons.

What are they trying to hide?

Off the air, I ask the hosts if they believe.

Host No 1: "You know why people talk about conspiracies? Because they exist."

Host No. 2: "When I was in Dallas they would talk about the hotel on the other side of the practice field having bugged rooms, because they thought [former Washington Redskins coach] George Allen had spies there."

Back on the air. No callers. What gives? The topic is sports inventions. A pill that helps you forget bad losses. Robot referees. Holographic televisions. The conversation shifts to cotton versus microfiber underwear. On it goes. We never take calls. Never talk plots. Maybe I'm crazy.

And then it hits me: This can't be random.

Nothing is random. Just hidden. Like the hidden hand. Their hand. And they don't want me to write this. Because they know I'm close. Too close. They could be league security. Or business managers. Or ex-CIA. Or the package-misplacing staff at my front desk. They could be sports talk radio call screeners. They could be sports talk radio hosts.

They could be anyone.

In August of 2009, Omega executive Christophe Berthaud admitted that Cavic "for sure" touched the pad before Phelps in Beijing.

For sure.

A fact.

No dispute.

So why isn't anybody saying -- or doing -- anything about it?

The '85 draft. I can't let it go. I'm back at the magician's house, my laptop deployed on his kitchen table. Freeze it. Right there. The 5:56 mark. Stern exhales. I'm watching his hands. He opens the clear plastic cylinder. Grabs three envelopes. Flips them over. Discards two.

Why the flip?

Why not take just one envelope in the first place?

Why, unless something is amiss?

"It's very easy to take random actions and add motive to them that doesn't exist," Richard Kaufman cautions. "People do that all the time. They see something and think that's part of the trick. But that's not the magic."

Sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke once wrote that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. The same holds true of sports conspiracies. Which makes Kaufman my last, best hope to spot the hidden hand.

And to prove to myself that I am not crazy.

Back to the cylinder. The envelopes are inside; both are huge. Perhaps for a reason? Stern addresses the audience: "The draw will be turned to further mix the envelopes ... "

"See that?" Kaufman says. "They haven't been mixed yet. That is a magician's trick. Just because the envelopes are in something that tumbles doesn't mean their order will change."

One spin. Pause. Kaufman's right. No mix.

"The larger the object, the less likely they will move around."

Two spins. Pause. Still no mix.

"You see? As they go around, they just fall as a lot."

Three spins.

Four spins.

Pause.

"OK, it appears they did mix," Kaufman says. "To make sure, you might be able to put a digital tag on each envelope. To watch their exact positions."

Onscreen, Stern selects the winning envelope. Flashbulbs pop. "The team whose logo is in this envelope will have the first pick in the NBA draft ..." I mention the freeze theory. Kaufman says it's possible. I bring up the bent corner. Kaufman asks if I've ever seen a Three-Card Monte trick. I haven't. From a black leather case, he produces a deck of cards.

"Watch," he says. He shows me three cards. A flourish. Where is the red card?

I don't know.

"In one of the scams, the three-card hustler bends the corner of the card, and then pretends he doesn't see it," Kaufman says. "He can bend and unbend the corner, so that everybody else bets the wrong corner and the wrong card."

The bent corner a red herring? I hadn't thought of that. Back to the footage. 5:58. Pause. Closeup of the envelopes. The outer corner of the bottom envelope appears crooked.

"The image quality isn't great. That could be artifacting."

Pause. 6:02.

"Oh, no question that's a bent corner."

Rewind to 5:59.

Kaufman points at the envelopes on the screen. "There are other possible corners there."

Pause. 6:01.

"It looks bent."

Rewind. All the way to 5:20, to Wagner slamming envelope No. 4 against the cylinder.

"I don't see him purposefully banging it."

Fast-forward. 6:04. Stern holds the envelope aloft.

"Is he unbending the corner? I don't see it. He would need to use two fingers. He appears to just be fidgeting."

Maybe. Maybe not. I'm confused. Lost in the same way magic tricks lose me. Am I seeing what I think I'm seeing, that Ewing-to-New York was a scam? Or is the very notion that Stern did not act alone determining what I see? (A different video clip of the lottery is on the right.)

The draft lottery continues. NBA security officer Horace Ballmer places the winning envelope atop a wall ledge behind Stern, under a placard reading "1." Freeze it. 6:13. Kaufman stands up. He's animated. Says there are tricks involving objects placed on easels and walls, tricks where the objects seen at the end are not the ones seen at the start.

"Pay attention," he commands.

Kaufman places a magic convention program in a wicker fruit basket on the far side of the table. He walks past a window, then past the basket, a different magic magazine in hand, shielding the basket with his body. "You just have to pass by like this ..."

Kaufman stops. He holds up the convention program. The other magazine is now in the basket. A switch. "And that was slow. It's easy. Just drop your other hand and keep moving.

"You know, the envelope could have been marked. It would be very easy. Like cutting a small piece of lead off a pencil and putting it under your fingernail ..."

Kaufman wags his index finger.

" ... and you can add a mark at any time."

The marked corner. Hadn't thought of that, either. Another way to make sense of the senseless, catch a sideways glimpse of the unseen. I feel a tingle. Giddiness and dread. Kaufman says he's done. Nothing else to tell me. I close my computer. On the screen, Stern and Knicks representative DeBusschere shake hands. A gleeful O'Brien exclaims, "Basketball is back in New York City!" The Starlight Room at the Waldorf-Astoria goes dark.

"Oh, one more thing," Kaufman says. "Write this down. WHEN YOU HAVE YOUR LAWYERS GO OVER THIS, DON'T PRINT ANYTHING THAT CAN GET ME SUED. OR ELSE I'LL TURN AROUND AND SUE YOU. Make it clear that I'm only speaking in what could be. And that I was very careful to say that."

The magician frowns. He sends me on my way. I think he thinks I'm crazy. But I know better. I have all the proof I need. Crazy to believe? Bent corners and frozen envelopes. Accounting firms and random drawings. The illusion of control. We all believe in something. Because the alternative is too much to bear. Because the only thing worse than the hidden hand is no hand at all.

Unless, of course, I really am crazy.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- 'Juice' Survives The Streets To Become Marlins' Barber To The Stars

-- LA-NY: History Of Championship Showdowns

-- The Exercise That Makes Body Fat Disappear

-- 3 New P90X Exercises That Blast Fat