For some fans, the statistical revolution of baseball -- featuring metrics like WAR, OPS and BABIP -- is at odds with the human elements of the game. In fact, they're inextricably intertwined. In The Shift: The Next Evolution in Baseball Thinking, Russell A. Carleton writes about making the data digestible and showing how the arguments between sabermetrics and traditional baseball culture hinge not on math but rather having the perspective to ask the right questions.

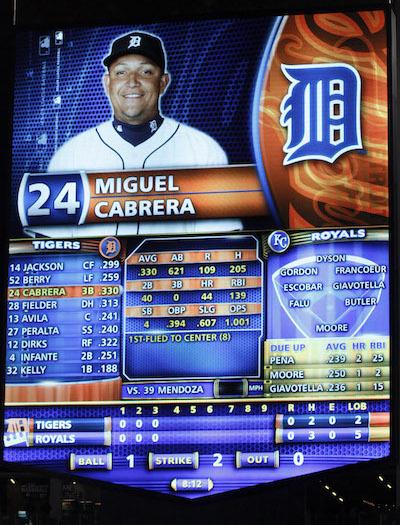

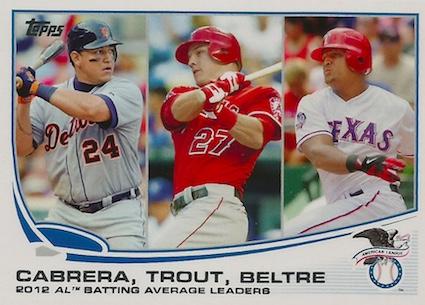

In 2012, there was a flashpoint in the ongoing cultural battle around the sabermetric movement. Miguel Cabrera of the Detroit Tigers won the first Triple Crown that Major League Baseball has seen since Carl Yastrzemski accomplished the feat in 1967. Cabrera led the American League in batting average (.330), home runs (44), and runs batted in (139). After a season like that, surely he was a lock to win the league's Most Valuable Player Award. Twenty years earlier, this wouldn't have been a question, but in 2012, there was another contender: Angels center fielder Mike Trout.

Trout, who was a rookie in 2012 (indeed, he won Rookie of the Year honors), played the first month of the 2012 season with the Salt Lake Bees, the Angels' AAA affiliate. When he came up to the majors in late April, he was an instant success, and ended up leading the American League in runs scored and stolen bases, while hitting for a respectable .326 batting average with 30 home runs and 83 RBI. Trout was universally hailed as having a very good year ... but Cabrera had won the Triple Crown.

That's when the "statheads" went to WAR. Not the thing where people shoot guns and missiles at each other, but the statistic Wins Above Replacement. According to WAR, Trout's contributions had made the Angels around 10 wins better than they would have been without him. Cabrera undeniably had a good year, but according to WAR, his contributions were "only" worth about seven extra wins to the Tigers. Trout, screamed the statheads, was far and away the more valuable player to his team. Who then was the MVP?

Partisans for Cabrera pointed out both the historic nature of a Triple Crown and the fact that Cabrera's Tigers won the AL Central and made the playoffs (and eventually the World Series, where they lost to the San Francisco Giants). Trout's Angels finished in third place in the AL West and made golfing reservations for early October. Cabrera was therefore not only a good player, but a good player powering a winning team.

Trout's fans pointed out that batting average was a very flawed stat, and while it was nice that Mr. Cabrera led the league in it, Mr. Trout's on-base percentage (.399) for the year was superior to Mr. Cabrera's (.393). They also pointed out that while the Tigers made the playoffs, this was an accident of geography. The Angels (89 wins) had won more games than the Tigers (88), but the Angels had the misfortune of playing in a division which included west-of-the-Mississippi neighbors the Oakland A's (94 wins) and the Texas Rangers (93 wins). The Tigers, on the other hand, played in a division of fellow Midwesterners, the best of whom (the Chicago White Sox) had managed only 85 wins. Trout was therefore the best player on a team that was actually better than Cabrera's, but the victim of a map!

Cabrera eventually won the Most Valuable Player Award, garnering 22 of the 28 first-place votes cast, but the argument remained. Which of them was the more valuable player? Aside from pedantic nonsense about the ambiguity of "valuable," a more interesting word that emerged in the inevitable think pieces on the subject was "tradition." Batting average, home runs, and runs batted in were statistics that had been used for decades to mark a player's quality. They are still the ones that are shown on TV when a batter comes to the plate. Why did the nerds need to invent a bunch of new convoluted numbers?

The answer to that critique is already partially finished. Batting average is flawed mostly because, as we just discussed, it pretends that walks never happened. Home runs are wonderful and not a bad statistic to focus on, although they represent only one way to contribute to a team. Runs batted in have the flaw that a batter who comes up with more runners on base -- something not in his control -- is going to have more opportunities to rack up RBIs. Yes, it is undeniably good to have a higher, rather than a lower, batting average. Yes, it is better to drive a runner in than leave him stranded. Yes, a home run is the best possible outcome an at-bat can have. And yes, Miguel Cabrera was the best at all three in the American League in 2012. Fans of Cabrera were asking a question: "Who led the league in batting average, home runs, and RBI?" Historically, that question had always been answered: "the League MVP."

Fans of Trout were asking whether that was even the right question. In that sense, advocates on both sides ended up talking past each other, because they both had the right answer to their chosen question. Which side was asking the right one?

I think it's reasonable to say that the Triple Crown stats are a pretty good indicator of a player's value. I also think that there are other numbers that do a better job. In most other parts of life, "the old stuff works fine, but the new stuff works better" is a winning argument, but I also need to recognize that there's something else going on here. Baseball is a game awash in numbers. It's been that way for a long time. While baseball's numbers form a functional lexicon that can be used to describe a player (e.g., he's a ".280 hitter"), those numbers are also intimately tied to stories -- sometimes legendary stories and cultural touchpoints -- in the game.

In 2012, Miguel Cabrera was a better hitter than Mike Trout, but Trout was the more valuable all-around player. Trout stole 49 bases (leading the American League) compared to Cabrera's four. That's 45 extra times that Trout effectively turned a single or a walk into a double. In 2012, Trout had 27 doubles and eight triples, for a total of 35 extra-base hits, while Cabrera had 40 doubles and no triples. While Cabrera had the edge in raw numbers of extra-base hits, Trout was standing on second base just the same after a single and a steal, and he was standing on second base more often than Cabrera. In addition, Trout was one of the best in baseball at adding value with his baserunning, "stealing" extra bases in other ways, while Cabrera's baserunning rated as below average. On defense, Mike Trout saved the Angels around 20 runs in the outfield, making him one of the most valuable defenders in the league, while Miguel Cabrera played an adequate, but slightly below average third base. Add it all together, and according to WAR it was Mike Trout by three lengths.

The most dangerous thing in the world is the correct answer to the wrong question, because it often stops further examination. A person can honestly say, "But I've got the right answer."

In 2012, Miguel Cabrera won the MVP Award, meaning that voters were asking a different question than the one that WAR answers. Perhaps they were answering, "Who led the league in three statistical categories that have traditionally been valued within baseball culture as the exemplars of hitting excellence?" In that case, they got the correct answer to their question. Were they asking the right one?

If we're to understand baseball -- or anything -- better, then the way to do that is with better questions. Before you answer any question, question the question first. If you want to understand sabermetrics, you don't need to fully understand the math. You just need to hold on to the moment of doubt that comes from wondering why batting average doesn't include walks. Why are we asking a question that pretends that something that really did happen never happened? If a question itself doesn't make sense, then the answer to that question isn't worth much. That's the real goal of sabermetrics. It's not creating Byzantine numbers for the sake of creating them. It's about asking better questions about baseball. The math works itself out.

-- Excerpted by permission from The Shift: The Next Evolution in Baseball Thinking by Russell A. Carleton. Copyright (c) 2018. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Russell A. Carleton on Twitter @pizzacutter4.