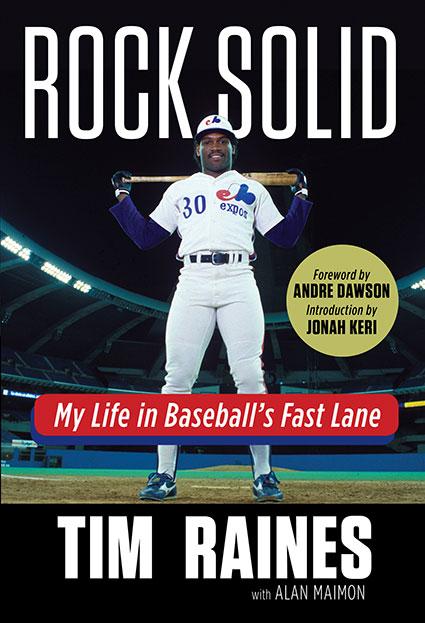

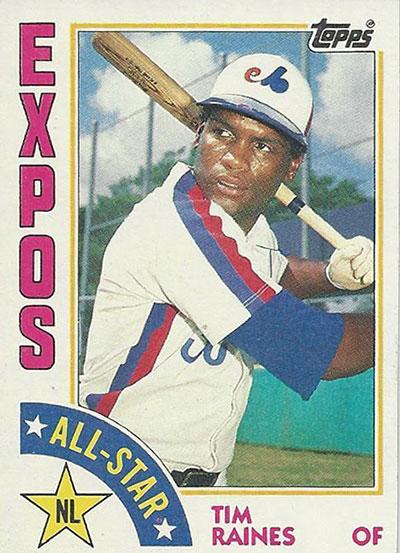

Tim Raines was a seven-time All-Star, a National League batting champion and a two-time World Series winner. When he retired in 2002 after 23 MLB seasons, he ranked fourth on the all-time list for stolen bases with 808. He will be inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2017. His memoir, Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane includes details about how he entered treatment for substance abuse for cocaine addiction in 1982, testified at the infamous Pittsburgh drug trials in 1985 and got back on track as one of the game's most exciting stars.

It's incredible what a difference two days can make.

On June 27, 1982, I stood on top of the world, fresh off the type of game that had solidified my reputation as one of the fastest-rising stars in the major leagues. In a Sunday afternoon win against the Pittsburgh Pirates that brought my Montreal Expos within a game of first place, I went 3-for-3 with two walks and three stolen bases.

Not a bad performance considering I had been up all night partying on Crescent Street in downtown Montreal.

With a day off before our next series at Olympic Stadium, I decided to keep the good times rolling. I hit up the locales where I knew I could score cocaine, which had become my drug of choice earlier that season. The next 48 hours were a blur. As I crisscrossed Montreal, snorting line after line, my mind started playing tricks on me. I saw objects and heard voices that weren't there. By the end of my 48-hour binge, I was drained of all energy and emotion, lying on the floor of my apartment at the Chateau Lincoln, staring up at the ceiling and feeling like I was going to die. I hadn't slept for three days, or maybe it was five. I had honestly lost count. I was afraid to give into the exhaustion. If I went to sleep, I feared I might never wake up. As one of my favorite bands, Chicago, once asked, "Does anybody really know what time it is?” Well, back in those days, I often had no clue.

We had a game that Tuesday night, and the Expos needed me. But I needed another fix to get me back on my feet. That meant my team would have to wait, because in the summer of 1982, everything took a backseat to cocaine, even the game I loved.

As the walls of my apartment closed in on me, cocaine consumed me both in body and in spirit. The ringing of the phone awakened me from my trance. Somehow I rolled across the room and managed to pick it up. Most junkies would have just ignored the call. I didn't realize it at the time, but my effort to reach the phone meant I wanted help.

The call came from someone in the Expos front office who was wondering where the hell I was because our game against the Mets was about to start. I can't tell you who placed the call because junkies aren't the most detail-oriented people on the planet. What I do know is that the fear of having my secret exposed momentarily jolted me to my senses. I muttered something about a case of food poisoning, a terrible headache, and problems of a ... umm ... personal nature, hoping that one of those excuses would stick.

When I think back to that night, it's with a mixture of embarrassment and gratitude. I never thought I would, but I ended up falling into a trap that ensnared many baseball players of that era. Years before steroids became baseball's Public Enemy No. 1, coke reigned supreme among certain major-leaguers. Regardless of what city you played in, cocaine could easily be found, for the right price. If you had told me when I broke into the big leagues in 1979 that I would be seduced by the charms of the white powder, I would have just laughed in your face. Prior to making the majors, I never drank, smoked, or did drugs. I barely ever cursed or stayed out late. You might say I was a boring guy. Throughout my life, baseball and other sports had always been my sole passion and focus -- my drugs of choice.

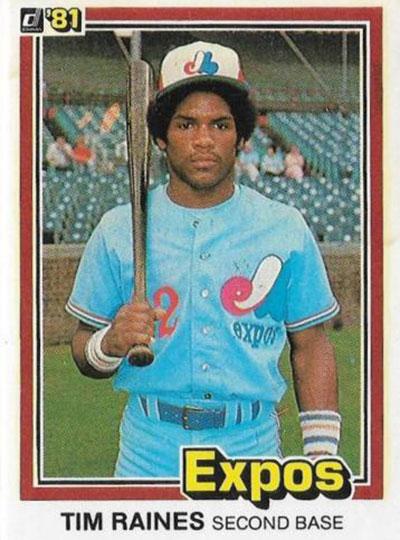

Was it a case of too much, too soon? Probably. During the strike shortened 1981 season, I stole a rookie-record 71 bases in 88 games and hit over .300, becoming one of a select group of players ever to make the All-Star team in his first year. The sportswriters pointed out that the strike had likely cost me a chance to break the modern-day record for steals in a season, 118, which belonged to Lou Brock before Rickey Henderson shattered it in 1982. My overnight success thrust me into the spotlight. A prominent baseball writer went so far as to proclaim that I was helping to revolutionize the game. "In case you've been away for about a decade, baseball has changed," wrote Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post. "Fundamentally. It's guys like Tim Raines who have done it." Boswell cited a 1981 game against the Los Angeles Dodgers in which I scored standing up from first base on a routine single to right field. "When Raines gets on, it's as though the groundskeepers accidentally put the bases only 80 feet apart and he's the only one who's found out yet," Boswell continued. That made me feel special. It also made me believe I was untouchable.

If it weren't for Fernando Valenzuela's incredible start in the majors, I would have easily won the National League Rookie of the Year award. And if it weren't for Fernando's Dodgers, the Expos would have reached the World Series in 1981. Maybe a less dramatic start to my career would have resulted in a smoother maturation process. As it stood, there I was, less than two months into my first full season in the big leagues, on the cover of a national sports magazine. The dose of quick success led me to believe that I had it all figured out. Instead of committing myself to taking my play to an even higher level, I took my gifts for granted. After cocaine got a hold of me, it didn't take long for Rock to hit rock bottom.

The problem snowballed quickly, excuse the pun. Playing in a foreign city full of temptation, walking around with an air of invincibility, I succumbed to peer pressure and allowed some of my older teammates to lead me astray. Montreal was a party town, but ironically, I got my first introduction to cocaine back in my sleepy hometown of Sanford, Florida, after my rookie season. I wanted to party like a star. So when some old high school classmates pulled out some coke, I figured, why not? I soon found out that the drug gave me a feeling that bordered on all-powerful.

When I returned to Montreal for the 1982 season, I brought my newly discovered taste for cocaine with me. And that led me to hang out with the wrong group of Expos, the ones who cocaine had firmly in its grips. Some of them had been using the stuff for years. On game days, they'd show up in the clubhouse after a long night of partying, put on their uniforms, and go out and play ball. I didn't think the drugs made them better players, but as far as I could tell, it didn't make their performance suffer, either.

When you're far from home and trying to fit in with your older teammates, it's amazing how quickly you can go down a dangerous path, especially when you have more money in your pocket than you've ever had before. During the off-season, I signed a contract that bumped my pay from $35,000 to $200,000. That kind of cash allowed me to afford the $1,000 a week I spent on cocaine. The possibility of getting hooked didn't cross my mind. As far as I was concerned, I had everything under control and could stop whenever I felt like it. Other people -- weaker people -- became junkies. Not me. I was very naive.

I tried my best to conceal my behavior from the world. But like any addict, I went to reckless lengths to make sure my habit got fed. On the road, I would meet with shady drug connections I got to know through my teammates. At home, I'd leave cocaine lying around the apartment. My wife at the time, Virginia, got wise to my problem and dumped my stash down the drain on more than one occasion. It worried her a lot. She hoped that I was just going through a phase.

The drug-related anecdote that the media jumped on and elevated into legend involved my tendency to keep cocaine on my person during games, specifically snug against my butt in the back pocket of my uniform. It's undisputed truth that I would sneak a snort in the clubhouse bathroom between innings, but the part about making sure I slid headfirst into bases so as not to break the vial of coke is somewhat exaggerated. Anybody who remembers my style of play knows that I went into bases headfirst long after I stopped carrying coke around with me.

Sometimes in the throes of a post-cocaine crash, I'd doze off in the dugout during games. Fortunately, games back then usually clocked in at around two hours. I probably would have had to lay out a sleeping bag if I had participated in too many marathon games. I learned that summer that when the exhilarating high of a drug wears off, a crippling low sets in. Your body and brain crave more. So you either give them more or you become a physical and mental mess. That's what makes cocaine addiction such a vicious cycle.

Missing that late June game against the Mets ended up being a blessing in disguise. Following the evening wake-up call, the Expos dispatched team doctor Robert Broderick to my apartment to check on me. I told him through the door that I needed to throw some clothes on, and I rushed to the bathroom to get rid of whatever coke I had on hand. The moment I flushed the powder down the toilet, I thought, What the hell did you do that for? That's the balancing act of an addict. As much as I wanted to avoid getting caught, I also didn't like the idea of flushing hundreds of dollars' worth of drugs down the john. The doctor didn't need to see the drugs to know I was afflicted by something far worse than food poisoning. I didn't know what to do, and my mind wasn't clear enough to come up with a plan. I felt scared. So I just followed my instincts and confessed what had been going on with me. The next day, I met with team president John McHale. He listened closely as the words came spilling out of my mouth. He didn't get upset. He just took it all in, like an understanding father.

I don't know if my confession surprised the front office or not. In 1982, I tried to maintain the appearance that I was ready to play every day. Though I still put up decent numbers and led the National League in plate appearances, there were times when I felt frozen in place, unable to see balls pitched to or hit at me. Several times, I dove out of the way of pitches that were clearly strikes. One of those times, I dusted myself off and asked the home-plate umpire how close I came to getting hit in the head. "Er, that pitch was right down the middle of the plate, son,” the confused ump replied.

I wouldn't have been able to keep my drug habit a secret for much longer. One downside of playing in Canada was that we had to go through customs every time we returned to the country, a process that often included drug-sniffing dogs. Looking back, I'm thankful that I had enough judgment not to transport any narcotics over the border. Otherwise, my problems could have been much worse.

I take full responsibility for my actions. No one put a gun to my head and said, "Hey, snort this.” That's why, when asked by team management whether others Expos were taking drugs, I never revealed the names of teammates who I knew were also abusing cocaine. I was a young, up-and-coming player who the Expos had a vested interest in supporting through hard times. Some of the other guys with cocaine problems were at the tail end of their careers, making them more expendable. I didn't want to be the reason that any of them lost their jobs.

To be perfectly clear, the majority of my Expos teammates had nothing to do whatsoever with what a handful of us were doing. Many of them went on to have great careers in baseball, such as Tim Wallach and Terry Francona; Doug Flynn went on to head up the state of Kentucky's anti-drug program. I can only imagine that my non-drug-using teammates noticed a change in me. When you spend almost every day with someone for six months, you pick up on even the slightest behavioral changes. In my case, we were talking about a complete personality transformation. But I was still relatively new to the team, and a lot of my teammates didn't know me that well. Even if they did detect that something was wrong, their instinct may have been to mind their own business. I can't blame them for that.

In 1985, I became the only Montreal player to testify before a Pittsburgh grand jury looking into the cocaine epidemic in Major League Baseball. I had to live with the reality that Tim Raines, the exciting young ballplayer, had been replaced in the public eye by Tim Raines, the recovering coke fiend. It was up to me to choose how I wanted the rest of my career defined. For that reason, confronting my addiction and getting help to beat it represented the most formative chapter of my career. It sped up my maturation process.

Drugs don't free you. They greatly limit you. After I kicked the habit, I vowed to play every game in the most uninhibited manner possible. The only white lines I wanted to see were those on a baseball field. And I didn't want to be confined by the 90 feet between bases. When I reached first base, I wanted every pitcher catcher combo in the league to know that I was going to take off for second and that there was nothing they could do to keep me from getting there. I would learn to master the art of the stolen base by taking just the right lead and accelerating so quickly that only a perfect throw could get me out. The idea of being a one dimensional player didn't appeal to me, however. I also wanted to generate runs and knock them in. I wanted to bunt for hits and to drive balls over the fence for home runs. I wanted to track down every ball that came my way in the outfield. And above all, I wanted to have fun. To be that type of player, I needed to give the game my full focus and dedication.

There are a lot of cautionary tales in life and in baseball. Drugs have ruined a lot of careers. A former Expos teammate of mine once approached me at an old-timers' game asking for money to buy drugs. I realized that if things had gone differently, I might have been that guy. Cocaine wasn't just an Expos problem. How great would players like Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden have been if they hadn't struggled with drugs and alcohol? They'd both be in Cooperstown, that much I know. I got to know Darryl and Dwight when we all played for the New York Yankees in the 1990s. As Darryl once told Sports Illustrated, "We were young, famous, and rich. Nobody could tell us anything, and they allowed us to do whatever we wanted to. You know, once you cross over to the major leagues, you're supposed to [instantly] become a man, but you're not ... You're not a man just because you're 20 years old and in the big leagues. You're still a kid, and you've got a lot to learn about life."

Thankfully, I tackled my problem and moved past it. That turbulent summer of 1982 easily could have had long-term consequences for me. The Expos organization supported me all the way. McHale drove me to twice-a-week therapy sessions during the last months of the season. The Thursday after our last game of the season, the team sent me to a California rehabilitation facility to get clean. My parents flew out west to give me their support. They felt torn up inside by what had happened to me. I had kept my secret hidden from them, meaning they didn't find out about my problem until it became public. My mom and dad thought I had enough sense to stay away from drugs, so at first they felt anger toward me. But as time went on, I think they realized that I deserved credit for trying to atone for my human mistake. After I completed the 30-day program in California, the challenge became staying sober. Without the right support network, it's very possible I would have slipped back into addiction.

The day-to-day process of resisting the temptation of drugs and other vices can be difficult. The man most responsible for ensuring that I stayed on the straight and narrow was my teammate, Andre Dawson, who became a mentor and a great friend as I tried to pick up the pieces of my life and rehabilitate my image. I watched how Andre carried himself as a person and a player and decided that I would follow his lead. Behind his intimidating facade was a person who exuded warmth and kindness. And on the field, he pushed himself to be the best. He and Gary Carter were the hardest working players I ever saw.

-- Excerpted by permission from Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane by Tim Raines With Alan Maimon. Copyright (c) 2017. Published by Triumph Books. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Tim Raines on Twitter @TimRaines30. Follow Alan Maimon on Twitter @alanmaimon