Michigan battled valiantly Saturday before falling to Ohio State again, for the 13th time in 14 years. But the highlight occurred in the third quarter, during a TV timeout, far from the action.

During every Michigan football game for the past few years, they've honored a veteran, some going back as far as World War II. But even by those standards, Saturday's honored veteran was special.

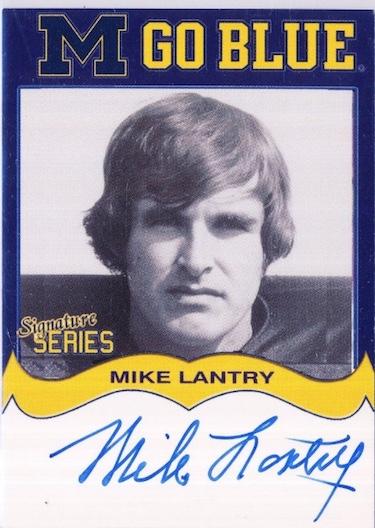

Mike Lantry grew up in Oxford, Michigan, where he starred in football and set a shot put record that lasted 50 years.

Lantry's father fought in Italy during World War II, so when Mike graduated from high school in 1966, it seemed only natural to sign up for three years in the Army. He joined the famed 82nd Airborne in Vietnam's Mekong Delta, near the Cambodian border. "There were so many snipers," Lantry recalls, "it looked like the Fourth of July every night."

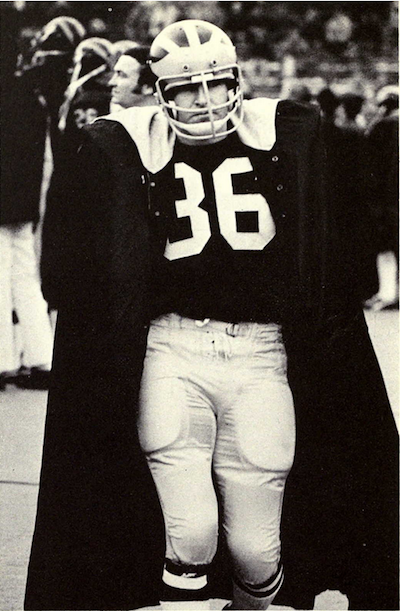

When he returned in 1970, he enrolled at Michigan and walked on to the football team.

Lantry never wore his Army jacket, or talked about the war. Of course, few of his classmates were eager to listen. Lantry wanted to get on with his life, which now included a wife and a son, Mike Junior, and kicking for the football program.

These were not ordinary teams. During Lantry's four years, Michigan won the Big Ten title every year. But then, Lantry wasn't an ordinary kicker. In 1973, he kicked a 50-yard field goal, Michigan's longest, then kicked another 51 yards just a minutes later – just one reason Michigan crushed its first 10 opponents that year.

That set up a showdown with Ohio State for the Big Ten title. The winner would likely have a great chance for the national title.

In the waning seconds of the game, with the score tied 10-10, Lantry had a chance to win it with a kick from the 44-yard line. His kick barely missed, and the game ended in a tie. For the first time in Big Ten history, the athletic directors broke the tie by voting to send Ohio State to the Rose Bowl. Michigan stayed home.

The next year Michigan was just as good, once again plowing through the first 10 games undefeated. Lantry set school records for most extra points and field goals, and had another chance to beat Ohio State with a last-minute field goal.

He lined up on the far-right side of the field, and blasted the ball so high it was hard to tell if he'd made it. Ohio State fans who sat directly behind Lantry would write letters to Michigan coach Bo Schembechler asserting that Lantry's kick was good.

But the referees waved it off. No good. As Schembechler later said of the game being played in Columbus, "Those refs knew where they were reffing!"

Mike Lantry walked back to the bench, and sat there by himself for an eternity. When the team bus returned to Ann Arbor, he remained in the back, long after his teammates got off, alone with his thoughts.

After an injury ended his NFL career, Lantry started a successful business he still runs today.

When Lantry looks back on his three years in Vietnam, and his three years on Michigan's varsity squad, he says the same thing: "I did my best."

But Lantry had never been thanked by his country for his service, or by Michigan fans for his play.

During Saturday's game against Ohio State, the announcer asked the crowd to turn their attention to the north end zone.

There they saw a 69-year old man with white hair and a white beard standing motionless, while the announcer re-introduced Mike Lantry to the faithful. They cheered while he told them of Lantry's tour of duty in Vietnam, his 33 games as Michigan's starting kicker, and all his records.

The cheering grew word by word, building to a crescendo. The Michigan crowd always cheers loudly for the veterans, and rightly so, but for Lantry, the cheers were a little louder, a little longer. They understood.

When the announcer finished, Lantry raised his hand, and stepped forward to the goal line, while 112,000 fans rose to their feet. They were giving him the bear hug he deserved back in 1970, and 1974.

Lantry stepped back, and the moment was over.

But, he said, "I'll remember that forever."

John U. Bacon is the author of five New York Times best sellers, including Playing Hurt: My Journey from Despair to Hope with the late John Saunders. His newest release is The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy, and Extraordinary Heroism. Bacon gives weekly commentary on Michigan Radio, teaches at the University of Michigan and Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism, and speaks nationwide on leadership and diversity. Learn more at JohnUBacon.com, and follow him on Twitter @johnubacon.