Les Miles hates his phone. It frustrates him daily. One time he tried to call an assistant coach on his LSU football staff. He instead dialed a recruit during a dead period. LSU self-reported the impermissible phone call to the NCAA the next day. Miles still blames his damn phone.

He never took the time to master it, which can be said of a lot in Miles' life. Football cannibalizes most of his time. Whatever's left goes to his wife and children. For the rest he skates by on guile and pragmatism. He learned, for example, how to send text messages. Miles needed a way to keep in touch with his teenage daughter, Smacker -- her given name is Kathryn, but her childhood lip-smacking branded her otherwise forever -- after she decamped to private school in Florida to join a nationally renowned swim team.

The distance chewed at Miles more than he anticipated, so he would send her texts to compensate. He spoke a different language to Smack. In April, during one of spring's quiet days, he punched in a text and hit send.

Your dad loves you very, very much. No. Way muches. Dad.

Miles' pocket buzzed a few minutes later. Damn phone. Of all the words to go to the wrong person, of all the people to receive the message, of course it was Hope. He studied the reply and laughed. To the world, Miles was the Mad Hatter: master of the malaprop, clock-management goof, fourth-down genius, coaching idiot savant. To Hope, he was just Les – just her older brother. And more than anyone, she reminded him of the canyon between who he is and who he wishes he could be.

After that day, he would never talk with her again.

They break the huddle with one word: "Championship." It's the middle of August and ghost chili hot in Baton Rouge, La., and even then they're thinking about Jan. 9, 2012.

For Les Miles' LSU Tigers, the hour-long trip south to the Superdome for the BCS title game feels more like expectation than hope, though nobody could've expected what the season would deliver. The nation's only perfect record. A brutal 9-6 overtime victory in the so-called Game of the Century at Alabama. And a rematch against the Crimson Tide in New Orleans at 8:30 p.m. ET Monday for the championship, which would be LSU's fourth and Miles' second in five years -- one more than Alabama's coach, Nick Saban, won with LSU before Miles replaced him.

Inside a metallic practice bubble that late-summer day, sweaty young men listen to red-faced coaches bark orders and demands. Even praise comes at excessive decibels. Miles, 58, is dressed in a gray shirt, purple shorts and his standard-issue white hat. He bears an eerie resemblance to Kurt Russell. Miles doesn't yell. He doesn't say much. He's most concerned with the ice cream man. A Blue Bell truck brought fruit-juice bars. Good, Miles says. Low-calorie. He likes to give his players treats. Sometimes he'll send out gofers to hack up a dozen watermelons on sweltering days. As a player Miles slogged through two-a-day practices that ate away at his resolve. He's not above rewards.

The seamlessness with which Miles transitioned the program from the no-nonsense, bordering-on-miserable atmosphere Saban bred to the loose, happy air that permeates LSU today is among his greatest successes. There have been setbacks. Before the Tigers' first game, nearly half the team broke curfew, including quarterback Jordan Jefferson, who police charged with felony battery for allegedly kicking a Marine in the head during a brawl. In the middle of the season, Miles suspended three more players, including Heisman Trophy candidate Tyrann Mathieu, when synthetic marijuana showed up in their urine.

"Those were things this team needed," Miles says. "It's a distraction. You can call it what you want. And it was. But there were direct, correctable steps, and they made 'em. And it was wonderful. It was fun to work with. It's been a fun year."

Only Miles can turn a bar fight into a fun time and still manage to sound sincere. He's the father who never allows disappointment to trump lessons learned, and never does Miles sound more like a dad than when he's talking about his players. He dotes on Smacker, his two sons, Manny and Ben, and his daughter, Macy. He deifies his wife, Kathy. He also knows all of their love is everlasting. The players' is fleeting, and so when Miles arrived in Baton Rouge seven years ago, he stressed to everyone on his staff and his team a universal tenet that felt right even delivered by a Midwestern carpetbagger: the importance of family and the forgiveness inherent therein.

He learned it from Bubba Miles, his mountain of a father who died in 2000, and Martha, his mother. She and Hope moved to Baton Rouge to be closer to Les. They found him consumed by his players and his wife and kids. Those were the two families for which he had time.

The arrest, the drug test, Manny sneaking out of the house at night – those were problems in Miles' bailiwick. He knew how to handle them. When in the middle of this season Martha Miles, 88, decided to ignore the staff at her retirement home and walk through traffic across a street, it left Miles in a rare state: speechless. Bubba's overwhelming personality had fertilized an independent streak in Martha that never faded. Miles saw his mom maybe once a month. She was going to listen to him as much as she did the nurses.

"It's like admitting this is a choice you've made and a significant one," Miles says. "When it's all said and done and you look back and ask where you spent your time, you better get it right."

The small, hardbound book is drowning under a deluge of paper. Amid the coffee-table books and iPads and documents that adorn Les Miles' desk, sometimes his little treasure gets lost.

"Lord," Miles says, looking toward the tall ceiling of his office, "you know I have to be honest with you. I've given this a lot less attention than I should."

He grabs the Bible and opens it. A picture of his youngest son, Ben, falls out. Doctors removed his appendix the previous day, and Miles wanted him to be closer to God. Ben wants to be a coach. Miles is quite certain he'll be a defensive coordinator.

"Look right here," Miles says. It's Bubba's name. When he died Sept. 13, 2000, Miles inscribed his dad's name and the date on a page with other important moments. He reads the rest of the notes, ticking off each of his children's names and birthdates as well as his wedding date with Kathy. Then he gets to his favorite part, with the looping L and M.

To: Les Miles

By: Dad

Date: Sept. 27, 1997

Bubba gave Les the Bible because he didn't want him to forget about what matters, or at least what he believed matters. Bubba advised more through cues and looks than words. When Miles graduated from Michigan in 1976 and returned to Elyria, Ohio, to join Bubba as a broker in the long-haul trucking business, he said: "Dad, I want to make a million dollars."

Bubba's face creased with puzzlement. "Yeah," he said, "that's what you want to do."

In his first year, Miles earned almost $50,000, a staggering amount for a 23-year-old. "If he stayed in sales," says his good friend John Wangler, "he would've made a million dollars." Bubba sensed something was amiss. Miles ached for football. He would talk about it, Bubba would listen. It took a few years for Miles to convince himself. By then, Bubba's look had softened. Miles knew he should go, though not before a warning from Bubba: The inertia of this coaching life -- this mad concoction of perfectionism, testosterone, moral compromise and the potent drug of triumph -- can eat your soul. Don't let it.

Miles picks up his Bible.

"I get to pieces now and then," he says. "Matthew is my favorite."

He looks up again.

"Lord knows I should spend more time in it."

He sighs.

"There's always time for that piece. I have to make it."

Hope Browne always had her girls. She made sure to remind them: Even if their dad wasn't around, they had her, and she had them, and that was enough. Jessie was the wild horse, Katie the angel and Hope their foundation. When their home in Ohio burned down four years ago, they saw it as a fresh start. Off to Zachary, La., they went, about a half-hour from Miles' house.

She got a job with AT&T and spent free time painting and crafting. She and the girls would make gorgeous ornaments for the Christmas tree. Then the weather would warm, softball would start and Jessie and Katie would spend most of their time at the field. When they came home with bruises on their arms or legs, Hope wouldn't console them. She'd press the contusions and say: "Ding-dong!"

Jessie's high school coach, Leslie Efferson, knocked the sass out of her -- a mile running for every eye roll will do that -- and helped her grow into a college-level pitcher. Hope would take half-days off of work to watch the Browne battery, Jessie pitching and Katie catching. On the day Jessie signed a letter of intent for a full scholarship to Southeastern Louisiana University, Hope wiped aside her tears and told her daughter: "You're going places, kid."

"We were in a good spot," Jessie says. "A good little city to live in. She was happy to see us happy. She liked the life that we were living. We were really happy."

The family approach Miles introduced upon arriving at LSU wasn't just some ploy to rope in the holdovers from Saban. People inside the LSU athletic department genuinely, deeply care for Miles -- how well he treats them, how he allows them some semblance of a life outside football, how he affords them respect. How, in almost every way, he is the antithesis of Nick Saban.

They see, too, how he tries to prioritize his kids and wife. It's little things like going to their games, bigger things like bringing Ben along on a trip to the ESPN campus or working Manny and Macy into a video about old-school Converse sneakers that went viral.

The comments at the bottom are telling: Even Alabama fans can't help but love the sight of Miles parading around in purple shorts that look like they belong on John Stockton and woofing at his 8-year-old daughter after blocking her shot.

"His family means something to him," says Jack Marucci, LSU's longtime athletic trainer. "You'll see guys who say that but don't practice it. Les does. It's real. It's genuine. And it fulfills him."

Miles dragged his family from Michigan to Colorado to Michigan to Oklahoma State to the Dallas Cowboys to Oklahoma State before landing at LSU. If he can't promise stability, he can at least give them time. Or as much as the job will allow. When doctors removed a cyst on his brain Christmas Eve after his first season as a head coach with Oklahoma State in 2001, Miles returned to work soon thereafter. Kathy knew he would. They met at Michigan, where she was an assistant basketball coach, so she appreciated the job's magnetism.

"She herself understands the importance of how you've got to bring everything together and get people to sacrifice for each other," says Bill McCartney, who coached with Miles at Michigan and Colorado. "He couldn't have a better combination with the personality he has and to have that kind of a life mate with him. Their family is absorbed and consumed with his job. They're all in."

Trying to console Miles after LSU looked like it blew a shot at the 2007 title game with a triple-overtime loss to Arkansas, Kathy ginned up the classic "undefeated in regulation" marketing line that helped vault LSU to No. 2 in the final BCS standings. The Tigers beat Ohio State, and Les Miles was the national champion. In Louisiana, that makes you bigger than the governor.

Life changed, or at least it was supposed to. Miles wanted to get away more. A friend offered him a share in a boat where he could relax in the sun and ignore football. It was going to be a great summer. He would take a few days here, a week there, maybe more if he was lucky, time during which he and Kathy and the kids could do what families are supposed to do.

"I thought after the national championship I was going to be a different guy," Miles says. "I thought I was going to get this boat and have all this time. I still love boating today. But the reality of it is, I do few things, and I enjoy them greatly. I chase my kids around. I hang with my wife. And I coach college football."

Miles spent parts of seven days on the boat. He doesn't use it anymore.

"Les, have you lost your mind?"

When Bo Schembechler spoke to Les Miles, the words echoed as if from high above. Bo was a god in Michigan, and to Miles he was more: a new father figure, Bubba away from Elyria. If he was going to leave one dad, it would be to join his other. While Bubba urged Miles to chase his football-coaching aspirations, Bo did everything he could to convince Miles he didn't want to take an $8,200 job as a graduate assistant and fetch coffee for a living.

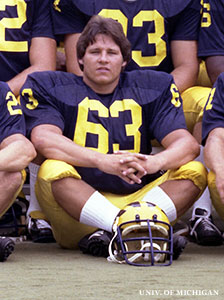

Only he did. The aura of a football field intoxicated Miles. It shaped his ideals, his worldviews. He reported to Michigan as a 6-foot-1, 210-pound offensive guard. Miles always would be undersized, and Schembechler said that was no problem. He was an undersized lineman as well, and it never handicapped him.

Miles wanted to provide for others what Michigan and Bo furnished him, even if it meant a ramen-and-peanut butter-heavy diet. Miles took copious notes on everything from schemes to Schembechler's affect when talking with players. He learned to delegate. By his second year, he foisted all the grunt duties on the other GA, John Wangler, who had just graduated after two years as Michigan quarterback. Wangler refused to do Miles' laundry, so Miles hunted around and found someone who would.

"You could tell there was something about him," McCartney says. "I think it's offensive linemen. They put family first. They believe the coaches. They care about everybody. They're unselfish. They're the fabric that holds the thing together."

McCartney and Miles got to know each other during morning jogs, and when Colorado hired McCartney as head coach in 1982, he whisked Miles west with him to coach the Buffaloes' offensive line. Miles grew into an ace recruiter -- he landed Sal Aunese, the quarterback who fortified a revitalized program -- before returning to Michigan as Schembechler's line coach. He was a "great recruiter" there as well, says Gary Moeller, who took over as Michigan coach after Schembechler retired following the 1989 season.

As Miles hopscotched to more jobs – offensive coordinator at Oklahoma State, tight ends coach with Dallas and head coach at Oklahoma State before his LSU gig -- he never forgot Michigan and hoped it never forgot him. When Lloyd Carr retired after the 2007 season, the prodigal son's return seemed a fait accompli, even if it meant Michigan waiting until after Miles coached the championship game to work out details.

That never happened. The cult of Bo had long run the football program, and athletic director Bill Martin wanted new blood. Even more, rumors fogged Miles' reputation around Ann Arbor, the sort repeated so often they were accepted as ugly fact. Miles departed Michigan in 1994, right after Moeller's drunken outburst at a local restaurant led to his arrest and firing. Even though Miles left to run Oklahoma State's offense, urban legend tied his departure to an affair with Moeller's wife.

"There is no substance to anything," Miles says. " ... It's from those people who felt like they needed to upend a candidate's opportunity and did so by any way they needed to do it. I do recognize reasons that people strategically choose to undermine other people. I understand it. But that can't hurt me. If it does, in the position you're in, everyone can take a swipe. All you need to do is read the Internet and get a tweet. 'Go (expletive) yourself, Les.'

"The reality is those people have real pain and sorrow and a disdain for what they do. They have a pitiful existence."

Moeller never has spoken about the arrest and declined to do so.

"But as far as Les Miles," he says, "no, there's nothing there."

It was enough to factor into Michigan passing up a national championship-winning head coach whose bond with the school remains covalent even after more than a decade of mudslinging. Martin eventually hired Rich Rodriguez. He went 15-22 and committed five major NCAA violations before being fired in 2010.

"What we think we want or is our plan sometimes isn't," Wangler says. "[Les] understands that. Not that it makes him feel better. If it's for the right reasons, you're not good enough. But if it's for reasons that aren't really valid, it's tough.

"Les is a big boy. He's always been very resilient. You can see how his teams play after they get beat. I don't think he dwells on it. I'm sure it's tough. He went to school at Michigan. He loves it. But he's an SEC guy now."

Miles can't remember the last time he texted Hope before the accidental message. He coaches the best football team in the nation. He operates on four hours' sleep, waking up at 4 a.m. so he can squeeze in work before sending his kids off to school. He does what feels right and overlooks the rest.

Life happens. Relationships evolve. People grow apart -- even brothers and sisters. In that way, he's no different than any of us.

"I wasn't a perfect brother in any way," Miles says. "I think you have to be honest that way. You have to tell the truth. I probably could've been more giving, and I probably was not.

"I am content with it. Because what choice do I have?"

Nobody knew quite what to make of the grown man doing snow angels in the end zone of Sun Devil Stadium. Never mind the lack of snow, either. In the immediate aftermath of a Les Miles-coached game, when his synaptic functions remain shot, he is liable to do anything. And the pure, unencumbered joy that sheathed him following his first game as LSU coach prompted him to shed whatever inhibitions he might have.

Only a few people saw Miles flop to his back and gaze at the sky in Tempe, Ariz., after a game-winning touchdown with 73 seconds remaining in LSU's 2005 season opener. He needed it. His players needed it. Louisiana needed it. Hurricane Katrina hit two weeks earlier. Almost three-quarters of Miles' players were from Louisiana. And leading them through it was a guy who literally thanked his lucky stars for the first win.

The skepticism around Miles wasn't rote. Nobody could compare to Saint Nick, who returned LSU to glory after a 45-year championship drought. The New Orleans Times-Picayune questioned Miles' charisma. Fans slagged his propensity to burn timeouts or mismanage two-minute drills. He was pegged an outsider even though Saban had a similar pedigree. Two years after his championship, following a 9-4 season, athletic director Joe Alleva posted a letter to fans reminding them "LSU is committed to having a football program that regularly plays for championships," as if that needed saying.

Whatever frost remained between the Tigers' fickle fan base and Miles seemed to thaw Nov. 6, 2010, when LSU upset fifth-ranked Alabama in Baton Rouge. Miles' trickery flummoxed Saban: A fake-punt run first, a tight-end end around later. He bent over, plucked a blade of grass from the Tiger Stadium turf, placed it on his tongue like a sacrament and ate it. He was crazy -- their kind of crazy, perfect for a place where they call one another coonasses and it's a term of endearment.

Long before that game Miles had sold his players. It's more than the winning, more than the nine first-round draft picks in his first six seasons, more than how he became one of them. Miles will walk into the players' lounge at LSU's football complex, survey the scene, try to decipher Louisiana-speak. Once he figures out what's going on, he'll crack a joke.

"I don't think he's ever had a good one," says All-American cornerback Morris Claiborne, the latest projected first-rounder.

What convinced them was what convinced everyone else around the program: The treatment, the respect, the camaraderie -- the family. Some coaches run their team like a bottom-line CEO. Miles wants to be the boss who cares, even if that meant suspending Jefferson until authorities reduces the charge against him to a misdemeanor. He returned after LSU's fourth game, by which time they'd beaten three Top 25 teams, and reclaimed his starting job after the brutal, intense battle against Alabama.

It turned into Miles' signature victory, bigger to the fans than the BCS title. With an off-week before the game, Miles wanted to keep his players motivated and wallop them before the game with a speech. The players expected it. Claiborne remembers a speech Miles gave before a 2009 game against Georgia. He wasn't playing. "But I wanted to after listening to that," Claiborne says. "You can hear the sincerity in his voice."

Miles liked to draw on his speeches from universal themes. Instead of cracking Bubba's bible, he relied on verses sent weekly by his former Michigan teammate Calvin O'Neal. Before he led them into a hostile Bryant-Denny Stadium, Miles stressed unity and togetherness and family.

His final words stuck: "Make a dominant play."

They did, dozens of them, a pyramid of excellence. Already Miles had vanquished whatever yearning for Saban still loomed. Now he had guided LSU's No. 1-ranked team in the country over Alabama's No. 2 at the place where they built Saban a statue, on the field where the Crimson Tide had lost once the previous four years.

For that day, and maybe a lot more after, Les Miles was the best coach in America.

He was right, you know. Hope's dad did love her very, very much. No. Way muches. She was his only girl. He doted on her like he never could his three boys. She missed Bubba.

Swimming, softball -- as long as it was a sport, Bubba would coach it, and he taught Hope all she knew. She passed it on. Jessie was the ace for Southeastern Louisiana as a freshman. Katie heads to Georgia later this year on a full ride. An SEC school. He'd have been so proud of them.

Bubba still loomed over the family. His given name was Hope Miles, and he named his daughter Ann Hope Miles, and she didn't want to risk it petering out, so her first born was Jessica Hope Browne.

"Hope runs in our family," Jessie says.

The text worried Hope. Les never texted her. She couldn't quite figure out what it meant, so she replied with equal parts sincerity and befuddlement.

Well, thanks, Les.

After cursing his phone, Miles called Hope to apologize. Not just for sending her what he meant to send Smacker. "I didn't do that to you on purpose," he promised. It was that it took an accidental text to talk with her. Even though she brought her family to Louisiana, it didn't change their relationship. They still weren't much closer than before. Sure, Miles called on the girls' birthdays, and they'd get together every so often for dinner or a holiday or a big game. That wasn't enough. He wanted to be a better brother, but ...

He never finished that sentence because he worried it would hurt too much. Only Hope knew how it ended. She filled in those blanks years ago. Les was a football coach and a husband and a dad, and they'd see each other when they saw each other. Les told her it would be soon.

A few days later, while on a sales call in Addis, La., Hope pulled from Sugar Plantation Parkway onto Louisiana Route 1. Residents have asked for a stoplight because of a troubling number of accidents at the intersection. She didn't see the Dodge Ram approaching. It plowed into the driver's side of her Nissan Sentra.

Hope Browne died immediately. She was 54.

Les Miles needed to get back to Ann Arbor. An ugly storm had pummeled the Detroit area in the winter of 1982. Ice slicked the road in the northern suburbs, where he and John Wangler were out recruiting, and they were due back home to report to Schembechler. Mother Nature was crapping all over their plans. If they could just get up a hill, they'd be on their way, but there was a line of cars at the bottom for a reason: Nobody was stupid enough to climb an incline in that weather.

"We can make it," Miles said, and Wangler called him all sorts of names as Miles gunned his black Buick Regal, made it halfway up and stalled. Undeterred, he eased the car down the hill, backed it up, tried again and met the same fate.

"I took an interesting shot at it," Miles says. "The magic was we made a decision early enough to make a run at it."

Everything about Miles' time at Michigan is sprinkled with that magic, the pixie dust that colors his experience. Michigan is where Miles learned to go for it. If he slid, so what? Better to try something and fail than regret not trying at all. And in a career built on the efficacy of those instantaneous decisions -- the snap judgments that build or break every coach -- Miles sees Michigan more as the place that honed his craft than one that doesn't need him.

"It is unbreakable; I will always be loyal to Michigan," he says. "It's the credential that marks my life. I met my wife there. My first child was born there. My father sat in that stadium and rooted for Michigan. I got a degree in economics. I was fortunate to be around one of the finest coaches and men that I've ever been around. I am in their debt."

It's why, after Rodriguez's firing in January 2011, Miles took a phone call from Michigan athletic director David Brandon. He always will listen to Michigan. "If I have a positive, it's loyalty," Miles says. "And if I have a negative, it's loyalty." The only explanation for his affinity toward Michigan would seem to be that unflinching allegiance, a devotion unbroken even by Brandon's call being nothing more than a courtesy ring. He had no intention of hiring Miles, not at the $3.75 million-a-year salary LSU pays him nor with the feelings about Miles in Ann Arbor what they are. Whether it's because of the rumors or his public proclamations that coaching Michigan was his life's ambition, it still doesn't quite register that the school twice passed him up.

"Being the head coach at Michigan was always Les' dream," Wangler says. "Dreams die hard."

Perhaps someday Miles will recognize Michigan for what it is: A place, a memory, an image -- a dream, yes, in that what he associates with it no longer is real. It is not home and it is certain not family, no matter how many times he hears a Michigan Man once is a Michigan Man forever. Family doesn't fake phone calls. Every conversation counts.

At very least, Miles can take solace in being the most successful outcast in recent football history. If he couldn't join 'em, he'd at very least beat 'em. And outside of the Alabama game, the 2011 Tigers beat the hell out of every team against which it lined up. LSU is outscoring opponents 491-131. When Miles sent his field-goal unit on to extend the lead against Arkansas to 41-17, Bobby Petrino, the Razorbacks' coach, wagged his finger toward Miles and yelled: "[Expletive] you, mother[expletive]."

"Right now, at LSU, to be in the Southeastern Conference -- that's as good as it gets," McCartney says. "Michigan does not have as good players as LSU. I'm not saying he couldn't do what he's done. But right now Michigan and LSU -- it's a mismatch. I think it's really hard to leave LSU. He's invested there now. His kids have grown up.

"Les Miles is another Bo Schembechler. He's LSU's Bo Schembechler."

McCartney says this not just because of an old affinity but because he sees it when he visits his grandson T.C. McCartney, a graduate assistant on Miles' staff. T.C. is the son of Sal Aunese, the star quarterback Miles recruited to Colorado, and he spent four years as a backup quarterback with LSU before joining Miles' staff. He relays stories about Miles, some idiosyncratic, others inspiring.

Sometimes he'll stand next to Miles on those wonderful nights under the lights of Tiger Stadium, when it's the loudest place in the world, and watch him genuflect in front of 92,542 people wearing purple and gold.

"Don't pretend for a minute that when I go down on my knee to eat a piece of grass that I'm just eating grass," Miles says. "There's a little message I'm asking for, and when I'm down there, I happen to pick up a piece of grass. I ask Him for intervention at any time I can get it."

In his right hand, Miles holds the Bible his father gave him. He hasn't put it down since he first opened it. He seeks guidance and wisdom. He knows the gospels can provide only so much peace.

"I loved my sister greatly, but in my life I have such a difficult time being close to anybody other than my family," Miles says. "What ends up happening in a life like the one I'm involved in here, I'm a poor brother and a poor son and hopefully a better father and coach and husband."

This is the narrative Miles has chosen, one he believes fulfilled itself when his mom scampered through traffic and when he never got to say goodbye to Hope. He crafted it inside the self-made bubble where being a coach and a dad and a husband and being a son and a brother are mutually exclusive, where one must preclude the other because Miles never has done anything half-assed, not laugh, not drive, not block, not live and certainly not love, and even if some roles call for that, it's not good enough for him. Bubba taught him to be the best. Bo taught him to be the best. It's what he knows.

"He can't be perfect," Martha says. "I know he loves me. He sees me. He gives me a hug. He always has the time to give me a hug. All I want is to stay back so I don't create too many problems."

She chuckles.

"I try to be good."

A couple weeks ago, Martha moved into a new assisted-living center closer to Hope's daughters. Her son Mark, who was born deaf, came from Ohio to live with her. Her other son, Eric, left behind his life in Virginia three days after Hope died in April to watch over Jessie and Katie.

"After this accident, your family steps up," Jessie says. "Whatever Uncle Les was before the accident doesn't matter. I can depend on them. I can call them. I know they'll be there."

On the way to Katie's letter-of-intent ceremony, Jessie's car got a flat tire. She buzzed Kathy, who was there within minutes to whisk her off to the signing.

"That to me is what a family is," Jessie says. "We definitely have that now."

More than ever, it's right in front of Miles. The coaching nomad can find stability. The father and husband and coach can be a son and a brother and even an uncle. Maybe it's not enough for him. It is for them. Ann Arbor isn't Valhalla. This is. This is home now. This is where his family is. All his families.

For one day, even if he didn't realize it, who he wishes he could be came to life. On Christmas, his mother and his brothers and his nieces drove the half-hour from Zachary to Baton Rouge. The kids played football. They watched movies. Les and Eric told stories about Bubba. His nieces sat rapt. His mom smiled. They ate and drank and laughed. It was magic.

At the end of the night, Miles promised he would see everyone soon, and he was right. The Miles clan intends to meet in a suite at the Superdome on Monday night, Kathy and Smacker and Manny and Ben and Macy, Martha and Mark and Eric and Jessie and Katie. In the locker room, Miles plans to carry Bubba's Bible and a picture of Hope and the fortunes of 122 kids in purple and gold.

And out the tunnel he'll run, the best football coach in America, ready for the biggest 60 minutes of his life, never happier to be who he is.

Other popular content on Yahoo! Sports:

• Giants' D-line flattens Matt Ryan, Falcons' offense

• Tim Tebow, Broncos deliver another miracle in win over Steelers

• Wild-card weekend's five top performers | Worst performers

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- LSU-Alabama Gumbo Bowl Cook-off: The Winning Recipe

-- One-On-One With ESPN's Erin Andrews

-- What LSU's Alfred Blue III Endured To Make It To BCS Title Game

-- Eddie George Is Julius Caesar. Seriously.