Last week, I was watching the "Late Show With David Letterman" with my mom (because that's how all good stories start).

Let me preface by saying Letterman is one of my comedic idols. He is one of the five funniest men alive and a league ahead of all other late night television hosts in the post-Johnny Carson Era.

But last week, in my mind, was not one of Dave's brightest moments.

"So, are any of you watching the World Cup?" he asked the crowd, followed by an applause.

"No, you're not," he responded, sparking laughter in the audience.

My mother, who is 51, laughed too. I, who am 21, did not. I have been watching the World Cup. My friends have been watching the World Cup. My generation has been watching the World Cup.

I originally expected to write a column about the World Cup being a hipster event to follow in the United States. During this year's Stanley Cup Finals, the NHL was referred to as a niche league. I felt soccer was similar, with places such as Seattle, Portland and Brooklyn boasting the face of American soccer fans.

As I watch this World Cup, at home, work and in public places, I have a different realization. Watching the World Cup is not a hipster act. It is a staple of my generation, millennials.

Forget Brooklyn. I feel as if I cannot walk into a bar in any borough of New York City right now that does not boast the flag of every nation in the World Cup. Every major U.S. city tries to one up each other on those streams ESPN uses to show fan reactions after U.S. goals. U.S. team apparel is flying off the racksand The American Outlaws have a presence in Brazil.

A lot has been made about the U.S. Men's National Team's infrastructure to develop players to compete on the World Cup stage. In the late 1990s, the IMG Soccer Academy in Bradenton, Fla., became the factory for U.S. talent. Landon Donovan, DeMarcus Beasley, Oguchi Onyewu, Bobby Convey, Eddie Johnson and Kyle Beckerman were among the early attendees to trade in high school for training in Florida. Michael Bradley, Jozy Altidore, Jonathan Spector and Aron Johannsson were part of the next wave in the mid-to-late 2000s.

While the physical talent was expanding, the U.S. did not wait for results to drive a following. It was doing the same with its supporters. The nation built the foundation for a following.

ESPN and MLS led the way by driving soccer into American culture. With the World Cup on U.S. soil in 1994, ABC/ESPN made groundbreaking steps for American television. They took commercials off soccer broadcasts. For the United States, this meant something. Viewing became about the sport, and it became much easier to watch. The Baltimore Sun joked, "We all know that only PBS goes without commercials. And we've all known for a long time just how un-American those people are."

The 1994 World Cup, the first of six for ABC/ESPN, brought a new feel. While some games were on tape delay, viewers got to see all angles of the tournament. Think back to the 2011 NCAA basketball tournament when television coverage went from one to four channels. The World Cup viewing experience exhibited a similar transition when ABC/ESPN took over in 1994.

Young people (I'm talking to people with 90s birthdays), think back to the way you understand technology now compared to your parents. For our millennial compatriots born in the 1980s, ESPN was the advanced technology they embraced and their elders could not comprehend.

The 1994 World Cup recorded a still-standing record attendance of 3.59 million despite being the last tournament to include 24 teams, rather than 32.

After another 1998 World Cup, Brandi Chastain and the U.S. sparked another surge of interest by winning the 1999 Women's World Cup. The final match was attended by 90,185 at the Rose Bowl, and it sent a message: Americans can play soccer.

On a personal note, my World Cup breakthrough came as a 9-year-old during the 2002 World Cup. Despite the unfriendly time difference between the U.S. and the hosts, South Korea and Japan, ABC/ESPN put every game on television. For four weeks, I watched every morning while eating my Eggo waffles before elementary school (the May 31-June 30 schedule was much earlier than this year's). I did not really understand what I was watching, but I knew I was witnessing an intense event featuring a bunch flags I had never seen before.

My dad told me the United States was terrible at soccer compared to other countries. As I watched the 2002 World Cup, I noticed the U.S. was doing pretty darn well. As a New York Yankees fan who only knew success (call me spoiled, but I literally did not consciously know a year the Yankees did not make the World Series), the tingly feeling of an underdog was fresh for me.

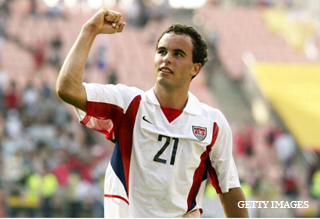

After the World Cup, I remember watching a SportsCenter clip showing Landon Donovan, the 20-year-old hero, receiving a standing ovation in his return to the San Jose Earthquakes. Donovan was awarded "Best Young Player" in the World Cup and gave my generation a face to match with soccer. I thought Donovan was cool, and more importantly for U.S. Soccer, I thought the MLS was cool.

Along with ESPN and MLS, an unlikely source helped spread soccer fandom among Americans currently in their 20s and teens: Humongous Entertainment.

Backyard Soccer debuted on Jan. 12, 1999. It followed with Backyard Soccer MLS Edition in 2001. Personally, I remember the third edition, Backyard Soccer 2004, which debuted on March 12, 2003. The game featured Clint Mathis on the cover, and since I considered myself a New York/New Jersey MetroStars fans -- I watched games when I happened to flip through cable channels at the right time -- I had to get the game.

The game had a stronger effect on me, as a sportswriter, than others, but Backyard Soccer 2004 became a hot topic among my childhood friends. We played at each other's houses and we tried to go the furthest in season play. The gameplay was easy, and my friends and I still reminiscence about features such as the indoor turf tournaments.

Most importantly, the MLS left a divot on children's minds ages 5-10. All ten MLS teams at the time had their names licensed to the game. I could name all ten teams before my tenth birthday. I also knew the players, who happened to be the U.S. National Team and MLS superstars at the time, disguised as "kid" forms of their adult selves.

Donovan was one of the most skilled players in the game, but Mathis and Convey provided firepower as well. Cobi Jones and Carlos Valderrama were favorites of my little brother and me due to their hairstyles. Brian McBride and Jason Kreis were lanky, while Jay Heaps and Chris Armas provided depth. Brandi Chastain and Tiffeny Milbrett could hang with the male players. In goal, either Tony Meola or Briana Scurry gave users a suitable backstop.

These are names that would go unnoticed without the game. When I heard about Kreis' December hiring as the first head coach of New York City FC, I did not think of his career in real life. I thought about how my 9-year-old self used him in Backyard Soccer. That may sound ridiculous, but the game was part of the engraining of U.S. Soccer in my life.

(Because apparently this really is a small world, after sending this article in for an edit Tuesday night, I coincidentally sat next to Kreis on a Metro-North train from the New York suburbs into the city. Of course, while I recognized Kreis, the non-millennials had no idea they were in the presence of a former MLS MVP. Kreis and I discussed the World Cup and the state of American soccer. I told him about how I honestly learned about him from Backyard Soccer and asked that he not be offended. He said his children loved the game. What are the odds of this encounter?)

Back in the real world, the 2006 World Cup continued to raise the popularity of soccer fandom. The U.S. team surprised many by tying Italy, the nation that would go on to win the tournament. (I always found it odd people did not make a bigger deal that the only game Italy did not win in the 2006 World Cup was against the United States). Losses to the Czech Republic and Ghana downplayed World Cup popularity in the U.S.

In 2009, a non-World Cup year, the U.S. woke up some fans. In the Confederations Cup, after losses to Italy and Brazil, the U.S. was left with a -5 goal differential through two matches. Then, the tide turned. The U.S. took down Egypt 3-0 and benefited from a 3-0 Brazil win over Italy, narrowly putting the U.S. through to the knockout stage. In the semifinal, the U.S. upset Spain, the defending Euro 2008 champion and future 2010 World Cup champion, 2-0.

During the Sunday afternoon (2 p.m. ET) championship match, the U.S. took a 2-0 halftime lead over Brazil on goals from 2010 World Cup poster boys, Landon Donovan and Clint Dempsey. One year before the World Cup, the U.S. was making noise. Although Brazil steamed back for three second half goals, Americans began to believe.

Perhaps this was most impressionable on young fans, who are always a little more optimistic than their older counterparts. My generation did not stereotype soccer as a non-American sport that the U.S. could not compete in, as many, what I will call currently grumpy, middle-aged people say about soccer.

The 2010 World Cup teams featured recognizable names like Donovan, Dempsey, Onyewu, Altidore and Tim Howard. It also helped the U.S.'s schedule opened with a high profile opponent in England. But an underrated factor was technology. ESPN3.com meant not needing to be in front of a television to watch the World Cup. In class, at work, in coffee shops, the ability to watch the World Cup spread.

In a downtime for sports when the World Cup started on June 11 -- Patrick Kane and Jonathan Toews won their first Stanley Cup on June 9 and Kobe Bryant won his fifth title on June 17 -- the youth had no excuse to miss a game.

Obviously Donovan's heroics versus Algeria pushed U.S. soccer nationalism among all Americans, but there is no doubt it left a bigger dent among young, impressionable fans. The drama of the 2010 journey left Americans salivating for another shot at glory, and it put 2014 on people's calendars. Young people can believe they will spend much of their lifetime watching a strong USMNT.

On a personal note, I attended my first soccer match that August. I was among the 77,223 fans that showed up for the U.S.'s 2-0 Aug. 10 loss to Brazil at then-new Meadowlands stadium in East Rutherford, N.J.

After the World Cup, something extraordinary happened: The FIFA (video game franchise) Revolution.

Football and baseball video games took too long in between plays, basketball video games could not master controls and hockey video games never really became popular (although EA Sports' NHL series is really darn good). EA Sports' FIFA was different. Games were short, gameplay was easy and multiplayer strived.

When soccer popularity rose after the 2010 World Cup, FIFA video games were a natural progression. Although the games had been around for two decades, the spike in soccer popularity drove sales. Young adults and teens were the people affected.

FIFA is the top-selling sports video game in the world. When Calvin Johnson was named the cover boy for NFL Madden 13, he admitted, "I play [Madden] rarely. I'm more of a FIFA soccer guy."

According to BloombergBusinessweek, soccer is now the second most-favorite sport among 18 to 24-year-olds. That does not exactly mean it is the second-favorite to play. FIFA is giving teens and individuals in their 20s of all physical abilities the chance to embrace soccer as a sport. The FIFA series also encourages an interest in soccer outside of U.S. Soccer.

Says EA Sports' general manager Matt Bilbey: "Young Americans are now developing emotional connections to teams like Real Madrid, F.C. Barcelona, and Manchester United through our game."

Finally, before the 2014 World Cup, the frequency of professional soccer on American television skyrocketed. The Fox Soccer Channel, which closed to make room for Fox Sports 1, brought in a healthy batch of top level European soccer matches after the 2010 World Cup. Due to the time difference, most of these matches, featuring domestic, Champions, Europa and other leagues, took place in the afternoon.

This meant the most common viewers were sometimes students, as young as elementary school and as old as college. ESPN bulked up its weekend soccer coverage, and NBC Sports eventually added the Premier League to its repertoire. While bringing in much smaller crowds, many of the same urban bars striving during the World Cup opened to young soccer fans on weekend afternoons over the past four years.

The World Cup does not represent just another sporting event to our nation's youth. It is not like the Olympics, which feature sports that most Americans genuinely do not pay attention to other than once every four years. More people in the U.S. followed soccer in the past four years than the snowboard giant slalom or the biathlon. I promise.

Middle-aged and older people do not get the youth right now. During their youth, not every World Cup match was on TV, not all the important European league matches were on TV during off-World Cup years and there were no video games to help casual fans get to know players. Obviously some middle-aged and older Americans have embraced soccer and the World Cup's popularity, but most stereotype soccer as un-American. They did not have such luxuries in their impressionable years.

As Dan Steinberg of The Washington Post explains, new media, staffed by people in their 20s and 30s, is showing a glimpse of the soccer generation showing its skin.

"Look at how Web sites like SB Nation and Deadspin and For the Win -- staffed largely by people in their 20s and 30s -- are covering this World Cup. The content is extensive, and interesting, and beautiful, and constant, and there is virtually no twaddle about whether or not the World Cup deserves blanket coverage in America," he says.

Whether ESPN, MLS, Fox, NBC, EA Sports, and yes, even Humongous Entertainment, realized it or not, they groomed us to watch and love the World Cup.

I hypothesize the next generation, Generation Z, will be "the soccer generation." Grumpy adults can say soccer will never become popular in the U.S., but I interpret the percentages differently. They keep increasing at an exponential rate. Technology is only going to advance and soccer coverage is only going to improve. That is not to mention the best U.S. players such as Clint Dempsey and Michael Bradley, are making life easy by playing in the United States. A new set of impressionable faces are getting a plate full of soccer.

To Letterman, I say you are the best. You really are. But you were wrong. I do not blame you. Your generation does not understand us.

But we are watching the World Cup. It is part of who we are. And it is only going to expand as time goes on.

-- Follow Jeffrey Eisenband on Twitter @JeffEisenband.