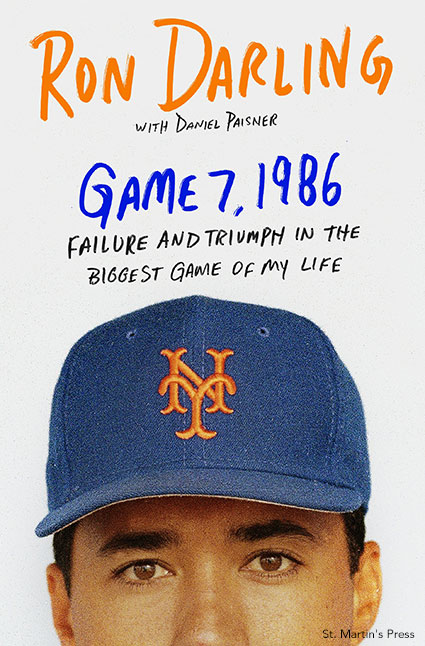

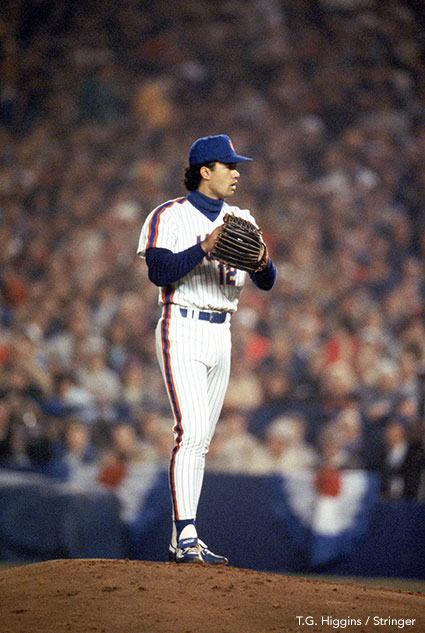

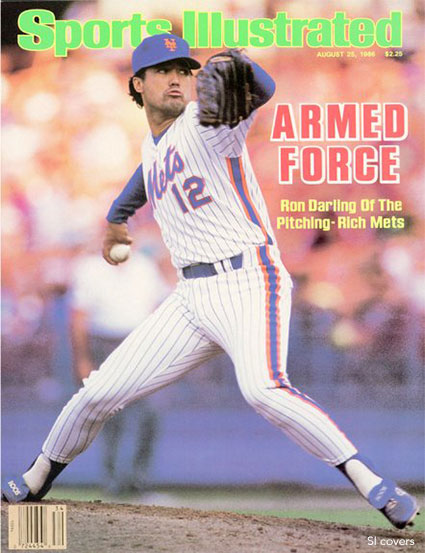

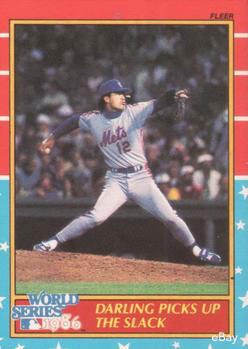

Ron Darling was the starting pitcher for the Mets on October 27, 1986, in Game 7 of the World Series against the Red Sox. Two nights earlier in Game 6, Boston had been one strike away from winning its first World Series since 1918. Then the Mets staged one of the most improbable comeback wins in baseball history and tied the series. In Game 7, 1986: Failure and Triumph in the Biggest Game of My Life, Darling recalls all the emotional swings while gearing up for his final start of the year, including why he left Shea Stadium before the end of Game 6.

I was wired a little differently on this from every single one of my Mets teammates, from every single Mets fan, from anyone else who might have taken in all of that Game 6 excitement full-on. Me, I could only experience the dramatic ending of that game in a sidelong way. I wasn't even in the building for most of those extra innings, so I'd ridden those ups and downs at a distance. For a couple of beats in there, I was on the Grand Central Parkway, headed toward LaGuardia Airport -- that's how out of touch I was with the emotions of this one game.

I suppose my absence during these late-inning heroics deserves an explanation. You see, in those days, with 50,032 fans shoehorned into Shea Stadium, it could take us up to two hours to get out of the parking lot after a close game. Our pitching coach, Mel Stottlemyre, was well aware of this and thought to use it to our advantage. Nowadays, teams might send a pitcher home early if he's due to start the next day, especially if the game is running long or headed to extra innings. On getaway days, they'll even send the next day's starter ahead before that day's game is under way. But back then this was something new -- something radical, even -- and on this night Mel became one of the earliest proponents of the practice when he found me with the score tied at the end of the eighth inning and told me to go home.

I wasn't expecting this.

Logistically, it made a lot of sense: beat the traffic, avoid the hassle, create this one extra edge over your opponent who might not know the chaos awaiting them outside the stadium. Personally, it left me feeling out of sorts, like I was abandoning my teammates -- even though there weren't a whole lot of foreseeable scenarios that would have put me in this game, unless one of our guys got hurt on the base path and we needed a pinch runner. Still, we were down 3-2 in the series, so there was the very real possibility we could let this adrenaline shot of momentum slip away and allow these Red Sox to end our season, and if that happened I'd want to be with my teammates.

Davey Johnson was on board with this strategy -- only here, headed into the ninth, our season still very much on the line, it felt a little premature. We'd just come back to tie the game at 3–3, against a shaky Calvin Schiraldi, our former Mets teammate who seemed to want to be anywhere but out there on that Shea Stadium mound at such a critical moment. Rick Aguilera, who'd done a great job for us in the series against Houston and who'd started to show the stuff that would make him one of the game's dominant closers in seasons to come, was coming in to pitch -- and, hopefully, shut things down until we could push across the winning run. At least, that was Mel's game plan. Granted, it was just Aggie's second year in the bigs, but we all had a lot of confidence in him. Mel was liking our chances. He liked Aggie's arm, the energy of the crowd ... the whole deal. It felt to him like we had the game in hand, and he said as much. He walked over to where I was sitting in the dugout and said, "Get your clothes on and go home. We're gonna win this ball game."

So I did as I was told -- reluctantly, but dutifully. Like I said, a part of me felt like I was abandoning my teammates. But I was feeling it, same as Mel. I was feeling it, same as the 50,032 wholehearted Mets fans jumping up and down in the stadium, willing us toward the finish line. I hurried out of my uniform and into my street clothes in the time it took for Aggie to retire the side in the top of the ninth.

Rice, Evans, Gedman. Strikeout, swinging; E6; ground ball double play. Not exactly one-two-three, but close enough.

I was in my car -- a sweet 1966 Mercedes 220, English-drive convertible -- pulling away from the players' parking lot as my teammates returned to the dugout. I had the top down. It was eerily quiet outside the stadium as I drove off. It felt like a ghost town a little bit -- with a swirl of hot dog and pretzel wrappers instead of tumbleweeds. Between innings, there had been all kinds of ambient stadium noises seeping through the iconic open-air ramps that used to frame that old building, but by the time I'd reached the Grand Central approach, there were only the still, sweet sounds of a late-October night. The roads were empty -- because of course the rest of the city was fixed on the game. The car had no radio, so I could only imagine what was going on inside the stadium.

Then, just as I was leaving the grounds, the night grew quieter still. (As if such a thing was possible!) The stadium seemed to heave -- or, better, to moan. (As if this, too, was a prospect.) There was a palpable, discernible, unknowable ... something.

Tough to notice, but at the same time tough to miss. If you're a lifelong sports fan, you've undoubtedly experienced a similar phenomenon. You're on your way into or out of a stadium, an arena, an athletic facility of any size or stripe, and you can tell right away that something has happened. Something big. Something of moment. Something calling to you in some way. Something that has nothing at all to do with you just yet, and yet you want in on it just the same. In baseball, you don't have to hear the crack of the bat or the roar of the crowd to know the ebb and flow of a game has turned; you can hear it in a kind of communal sigh. You can feel it in your bones. You can sense it. In triumph, the lifting of 50,032 hearts, all at once, can change the air currents in a visceral way, an exhilarating way; in despair, the soft fall of those same 50,032 hearts can suck the air from the night sky.

Oh yes, oh yes, oh yes ... there's a vibe that flows in and out of these big old ballparks that tells us right away that something's going on -- better believe it! -- and here it found me as I rolled onto the on-ramp, headed back to Manhattan.

Somehow, with no radio, no crack of the bat, no dialing down on the din of the crowd ... I knew. Somehow, with the top down, the windows all the way open, the roads fairly empty and the concrete jungle surrounding Shea Stadium all but silent ... I knew. I felt this cosmic tap on my shoulder that seemed to say, "Not so fast, Ronnie."

The game had turned.

Just how it had turned, I had no idea -- except it was a safe bet it hadn’t turned in our favor. If it had, the few drivers on the road would have started honking, flashing their brights, rolling down their windows and hooting and hollering. If it had, the joyous rumble from the stadium would have found its way to me. I would have felt a tap on my shoulder of an entirely different kind. Understand, at just this moment I was already driving away from the stadium on one of those one- way entrance ramps, so there was no turning back without hopping the curb. (Not about to happen in such a classic ride!) I had no choice but to ease on to the Grand Central Parkway and double-back at the first opportunity. Mercifully, fantastically, it only took a few minutes on these deserted roads, but as I was driving it felt like the longest few minutes in recorded human history. I was desperate to know what had happened to let the air out of the stadium as I pulled away, what was happening still.

There was no radio in that sweet old car -- this was back in the prehistoric information age, before smartphones. I was riding blind. Was it just that Aggie had given up a hit? Or were we now down another run (or, worse, another bunch of runs) and facing elimination? How was I to know?

What had happened, I'd soon learn, was that in the top of the tenth inning, Boston center fielder Dave Henderson led off with a home run down the left-field line. That was the first nail in the Mets’ coffin. But then Rick Aguilera managed to settle, striking out shortstop Spike Owen and pitcher Calvin Schiraldi, who hit for himself despite having just pitched two tough innings.

(Looking back at this game, from the perspective of a baseball analyst, I've always wondered about this decision by Boston manager John McNamara. You'd think a guy like this, a spot like this, the percentage move would have been to hit for the pitcher and throw out a fresh arm in the bottom of the inning.)

Next, Wade Boggs stroked a double to left-center and came around to score on a single by the hot-hitting Marty Barrett, the Red Sox second baseman. Another nail, and we were as good as done.

But I didn't know any of this at the time. I only knew that my teammates were up against it -- and I only knew that because of all that heaving and moaning coming from Shea. Within minutes, I had pulled around on the opposite side of the stadium from the players' entrance, in front of the old Diamond Club. I left the car at the curb with one of the security guys and dashed inside, like a scene out of a bad romantic comedy where the guy races to the airport to catch the girl before she boards her flight. Through the Diamond Club entrance, there was a back door to the clubhouse. It wasn't our usual route; you had to walk through a grand entryway dotted with framed photos and team memorabilia, and then through another waiting area where club officials often met with visit- ing league executives and other dignitaries. Then you'd walk through another door past the trainer's room, the doctor’s room, and the clubhouse attendant's room.

In those days, our clubhouse attendant was a guy named Charlie Samuels, and he was surprised to see me, just then, out of uniform. I wouldn't say he was happy to see me, just surprised.

Mets fans will recognize Charlie's name, of course -- he was with the team for over thirty years, but he left the organization in 2010 with his head hung low. He ended up pleading guilty to stealing bats, balls, bases, jerseys, and other memorabilia said to be worth millions of dollars, all told -- and as part of his plea deal he was banned from Mets games for life. But back in 1986 we just knew him as part of our extended Mets family. He was about the same age as a lot of the younger players, and a fixture in and around our clubhouse, and when I raced past his office that night he was watching the game on a small nine-inch television screen.

In those days, we all called Charlie "The Fig" after the pear-shaped actor in a Fig Newton commercial that was popular at the time. The Fig looked up from the set as I crossed the threshold of his office and said, "R.J., they scored two in the tenth." Like he was telling me there'd been a death in the family.

My heart sank. I'd expected the worst -- and here it was, the worst. I couldn't think what to say, so I just said, "F---!" To myself. To Charlie. To the baseball gods that had apparently let us down.

I leaned in close to get a good look at the screen. Just as Charlie was filling me in, I heard a door slam on the other side of the locker room. I heard what sounded like a chair being kicked over. Then I heard the unmistakable voice of Keith Hernandez, who had just flied out to deep center for the second out of the inning and also couldn't think what to say: "F---!"

-- Excerpted by permission from Game 7, 1986: Failure and Triumph in the Biggest Game of My Life by Ron Darling With Daniel Paisner. Copyright (c) 2016. Published by St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Ron Darling on Twitter @RonDarlingJr. Follow Daniel Paisner on Twitter @DanielPaisner.