Twenty-five years before Major League Baseball incorporated it into its All-Star proceedings, a home run derby competition featured some of the best players in history. It was the offseason, and nobody was in the stands. Thankfully, the cameras were rolling.

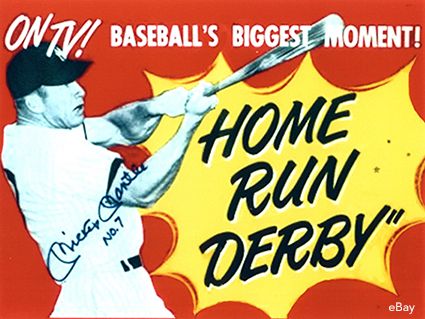

Filmed during a three-week period in December 1959, Home Run Derby showcased the game's top sluggers going head-to-head at Los Angeles' Wrigley Field, previously home to a minor league team. Twenty-six episodes were filmed and, because of the sudden death of the show's host, Mark Scott, there was no second season. It originally aired through the summer of 1960 on local stations across the country. ESPN acquired the rights to the show and re-aired it in 1988. Though every episode is available on iTunes (and YouTube), Home Run Derby remains somewhat of a hidden gem among baseball fans.

As Scott explained to the two hitters before each competition, anything other than a home run was an out. The batters alternated for nine innings, hitting as many dingers as they could before accumulating three outs in an inning. The winner received $2,000. The loser got $1,000. If a player hit three homers in a row without making an out, he received an extra $500.

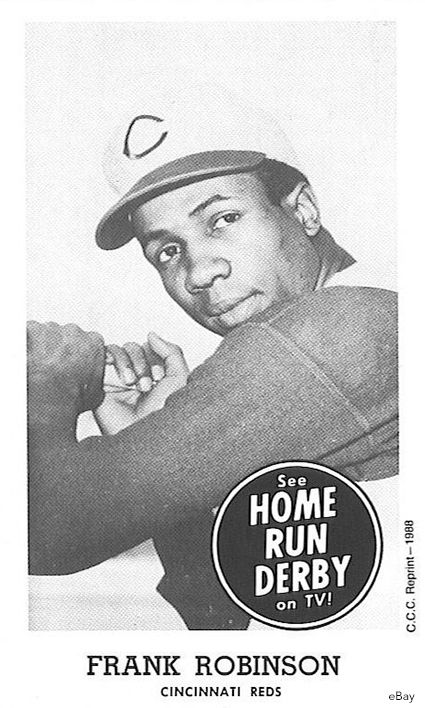

Frank Robinson, wearing his classic sleeveless Cincinnati Reds jersey during his two appearances, said "wow" when Scott discussed the bonus money. I recently spoke with Robinson and before I could finish my question about the significance of the payouts, he interrupted to say, "Hey, that was a lot of money back then."

What's the likelihood of getting today's players to compete in such an event?

"The taxes they'd have to pay would be more than $2,000," Robinson said.

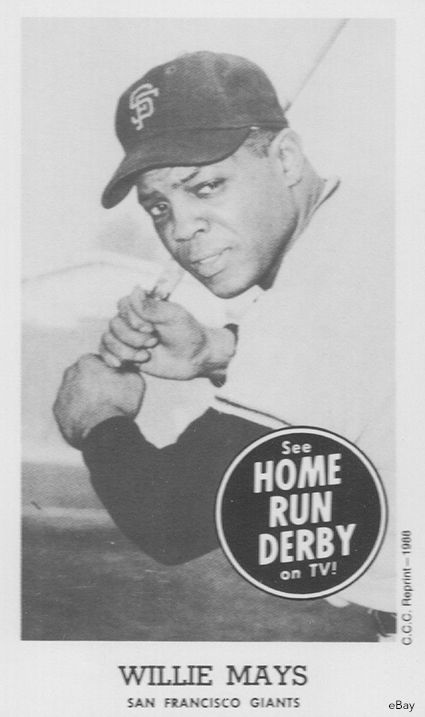

As a percentage of his 1959 salary, the $2,000 Willie Mays received for winning a contest would equate to nearly $750,000 for Miguel Cabrera today. (Mays and Cabrera were the highest-paid hitters in 1959 and 2015, respectively). I doubt, however, that Cabrera would make an offseason trip to California and hit baseballs in an empty park even for that hefty sum.

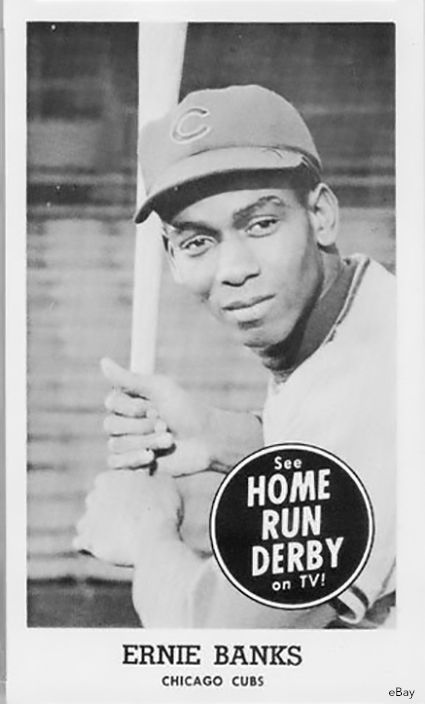

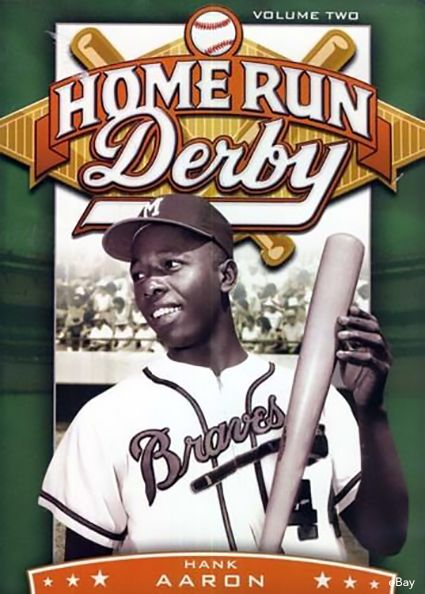

But Mays did. So did Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, Harmon Killebrew and Ernie Banks. Of the 19 participants, nine are Hall of Famers. They were chosen for their popularity and prodigious power. The World Series had been televised since 1947, but opportunities for fans to see out-of-market players were still rare, especially with no interleague play.

Thanks to Scott and Ziv Television Programs, we have footage (in black and white) of these all-time greats in uniform, crushing baseballs and chatting it up between at-bats. Robinson, one of six living participants (along with Aaron, Mays, Bob Cerv, Rocky Colavito and Al Kaline), said his appearance on the show was simply the result of being asked. Players of that era were known to compete in impromptu home run contests between doubleheaders. Some competitions, hosted by team owners, were more official. Robinson never participated because he didn't want to mess with his swing during the season.

"I concentrated on hitting the ball hard," Robinson said. "In a derby, it's a different approach because it's a home run or an out."

If the show had a winner, it was Aaron, who earned the most victories (six, in seven appearances) and the most money ($13,500). There was no bracket, however. Once a player lost, he was done, and the victor took on a new challenger. Several players did return weeks after being defeated. Scores ranged from 14-11 to 3-1 with the average being 7-4. It seems low for the game's best sluggers in a reasonably-sized ballpark (340 feet down each line, 412 to dead center and just 345 in the power alleys, though there was a 15-foot wall in left). As Scott pointed out each episode, the park favored neither a left-handed nor right-handed hitter.

We're used to seeing players routinely reach double digits in each round of the modern home run derby, part of the All-Star festivities since 1985. Robinson told me the modern 10-outs-per-round format allows players to get in a much better groove than they did with the show's format. "Also, [today's derbies] are during the course of the season," he added. "The players are in good shape."

Like many of the competitors, Robinson wore golf gloves for Home Run Derby, despite not wearing any during games. He doesn't remember it being cold -- Killebrew is seen blowing into his hands between innings during one of his four appearances -- rather he worried about getting blisters from swinging so much, especially since it was the offseason. Mantle, who went 4-1 in his appearances, is seen at different times wearing two gloves, one or none. He told Scott the glove(s) helped him get a better grip on the bat. The switch-hitting Mantle chose to bat right-handed, telling Scott, "Well, most all of my real long home runs have been from the right hand side of the plate." Eddie Mathews and Duke Snider, the two other Hall of Famers, were the only left-handed competitors.

Treating the hitters like golfers, Scott, a budding actor and sports broadcaster, didn't want to talk during pitches, which were served up by two batting practice pitchers who alternated innings. ("Incidentally, the pitcher who throws the most home run balls will also receive a bonus," Scott said during each episode.) The time between the ball landing and the next pitch was sometimes only five seconds, not nearly enough time for meaningful conversation. Even when Scott asked seemingly rhetorical questions, the players felt compelled to say something, usually a "Yes, that's right," or "He sure is, Mark." It is, at times, unintentionally funny.

After Mays gets off to a good start against Mantle, Scott says, "You're going to have your work cut out for you, Mickey," to which Mantle simply smiles and adjusts in his seat. This type of interaction was common. As Banks told The National Pastime magazine in 1997, "We could not believe we were on television and we didn't know what to say. Mark Scott was very relaxing. He kept asking us various things, but we were told to keep it going and make comments. But we didn't know how to make comments because it was very new to us."

The players come off as innocently polite, not so much the cliché machines athletes are today but somewhat uncomfortable and genuinely appreciative of the invite to the show. No matter the margin, the leader always assumes his opponent will mount a comeback. The closest thing to a controversial remark came when a pitch buzzed too close to the batter and Scott would ask the other player if he ordered the pitcher to do it. The most revealing interview was with Pittsburgh slugger Dick Stuart. When Stuart sits down in the middle of the ninth inning, Scott takes a deep breath and starts this conversation:

Scott: "You know, Dick, you and I know differently, but you had a reputation -- I don't know how it got out -- that you were somewhat of a pop-off guy. But I think it's enlightening for the people to see you here and see that you're just like any other ballplayer: You like your base hits, but you're not a braggart."

Stuart: "Two years ago I did say a few offbeat things but since then I've learned the hard way. Once you learn the hard way, you've learned for once and for all."

Scott: "You learned your lesson."

Stuart: "Yes I have."

Scott: "Well, you're a fine gentleman and a credit to the game of baseball."

A voice-over during the closing credits of each episode notes that "Home Run Derby is produced with multiple cameras," but the production is bare. It's hard to see the ball once it's hit, and there are certainly no distance trackers. The only sounds are the one-on-one conversations, the crack of the bat, and the home plate umpire yelling the number of outs. It's all very calming. In an era of crowded announcer booths and flamboyant calls, Scott's play-by-play is refreshingly simple.

"He got good wood on that ball and it might go all the way," he says during one call, his volume rising just slightly as the ball does the same. "Gone, over the left field fence."

What makes the episodes most enduring, though, are the players. The number of future Hall of Famers active in that era was about average, but no sport values its history as much as baseball, ensuring that Aaron, Mays, and Mantle will be viewed as legends in ways that Pujols, Harper and Trout won't. Gil Hodges, the oldest player to appear on Home Run Derby, made his major league debut in 1943 as a teammate of Freddie Fitzsimmons, who debuted in 1925. Aaron played through '76, the rookie year of Willie Randolph, who played until 1992. The show connected nearly 70 years of rich baseball history.

It's unclear why the creators chose "derby," typically associated with horse racing and soap boxes, as the key noun in the show's title. But the term, like the show itself, has lived on for generations.

Andrew Kahn is a freelance writer based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He writes about baseball and other sports at AndrewJKahn.com. Listen to his Scoop and Score podcast on iTunes. Email him at andrewjkahn@gmail.com and follow him on Twitter @AndrewKahn.

More MLB:

-- Mantle, Maris And Jim Gentile: The Story Of Baseball's Forgotten 1961 Sensation

-- How Oakland A's Helped Launch 'Hammer Time' And Mrs. Fields Cookies Empire

-- 'Battle Of The Bay' ... Remembering A's-Giants Earthquake World Series