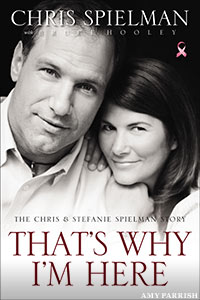

Chris Spielman was a high school and Ohio State football legend and a four-time Pro Bowl NFL linebacker, but he didn't tackle his toughest opponent until his professional playing career was almost over. In 1998, his wife, Stefanie, was diagnosed with breast cancer, and so began a 12-year journey that brought joy and suffering to the Spielmans, as well as hope and inspiration to thousands of others.

In That's Why I'm Here, Spielman traces his storied career, recalls his courtship of Stefanie Belcher, cherishes the growth of their four children, and invokes the deep spiritual faith that gave their family wisdom and comfort in times of struggle. Here is an excerpt:

The noble intentions I had for my children learning great life lessons from our cancer battle soon ran smack into the reality of me doing the everyday tasks their mother had performed. The result wasn't pretty.

When I made breakfast, lunch, or dinner, I quickly learned that if any piece of food touched another piece of food, it grossed out my children. The slightest contact between two separate things on the same plate made both completely inedible to them. They also recoiled in horror at the very notion of bath time. I think Maddie and Noah thought I planned to dump them in acid, not warm water. Some kids actually enjoy a bath, but my kids preferred sleeping in their own soot and grime.

While engaged in those battles, I also struggled to keep my head above water on the laundry front. When I played, even after I first got married, I took all my laundry and put it in my mesh bag at the stadium for the equipment guys to wash. They'd yell at me, but they always did it. Now I had to sort the clothes by color and use the right temperature when I washed them. It started out ugly, but I adapted pretty fast.

I used a lot of my football lessons to figure things out. Surviving in the NFL requires learning from your mistakes. Those who continue making mistakes soon lose their job. So I educated myself and got through it. The best thing about it? I learned little nuances about my kids that I didn't know before.

Stef had spent far more time with them than I had. When training camp started in July and throughout the season, I would see the kids for only an hour or two every night before they went to bed. During the off-season, I played with them a lot and we did things together as a family. But the bond Maddie and Noah formed with Stef six months out of the year made her the person they ran to when they needed something. Now the kids depended on me for almost everything. My routine differed from Stef's, and I didn't function as smoothly. But they adjusted and we made it work.

What little free time I had when not scrambling to corral a two- and a four-year-old, I tried to use educating myself on breast cancer. I wanted to understand what we were up against. I didn't want to leave any possibility unexplored if it could help Stef feel better or get better -- so I worked hard at it, just as in the NFL I studied game film for hours on end to make sure I got myself totally prepared. At first, I peppered the doctor with so many questions that he started ending every appointment the same way: "OK, Chris, what do you have for me this time?" It made me feel good to know I could ask him, "Why are we doing this? Why aren't we doing that?"

My research showed that sweets tended to hurt Stef's long-term prognosis, so I became pretty strict about what she ate. Now and then, she would sneak a piece of cake or a cookie, and I'd give her a serious look and say, "C'mon. We've gotta beat this thing." She had a sweet tooth and I felt bad for her, but I wanted to gain any edge we could, even if it was just percentage points. She took twenty vitamin supplements a day. I made sure we ate healthy as a family. I looked for anything that would help give her as much chance of winning this battle as possible. About forty of our neighbors stepped up and did a lot of the cooking for us. They did a great job following my order for foods low in fat, with no sugar, and plenty of green vegetables.

It truly inspired me to watch the determination and courage Stef showed as we moved toward her first chemo treatment. I know it scared her, but she never let on. She began journaling her feelings to cope with the stress and uncertainty she faced. That allowed her to voice some of her doubts and give herself an occasional pep talk, like she did in this entry from July:

Every single emotion she felt came pouring out in that entry. Facing the unknown left us both battling fear and desperation like we'd never known. We handled the roller coaster, thanks to a lot of prayer and the strength we received from the cards and letters that filled our mailbox every day. Our friends, and a lot of people we had never met, many of them cancer survivors, strengthened us with their encouragement and inspiration. Stef and I almost raced to the mailbox to get them. As she wrote a few days before chemo started: "It's like I joined some close-knit club when I got breast cancer. I would never choose to join this club if given the choice, but I'm so grateful to the women who want to help others through it. It is motivating, inspiring, and it helps so much."

She started chemo on August 4, less than a month after her mastectomy. Her arm and chest still hurt from the surgery, and now she faced having poison pumped into her system for months in hopes of killing the cancer cells. She looked right at the needle in her arm as the Adriamycin started flowing into her veins. For forty-five minutes, she rarely took her eyes off that bright red liquid entering her body, knowing full well it would wreak havoc on her in ways she couldn't yet comprehend.

The difficulty didn't take long to arrive. That night, right before dinner, Stef began suffering an episode of the chills and started feeling queasy. I made dinner, hoping it would help her feel better. Instead, she took one look and gagged. Within an hour, after eating just a little bit of fruit salad, she threw up.

The chemotherapy treatments continued once a week for five months. I stressed to Stef that despite how lousy she felt, chemo was the good guy. Although the side effects stank, chemo was our ally.

She had to take steps backward at first to take steps forward in the future. I tried, like a coach, to keep her focused on getting better and thinking positive. She bought in completely because she resolved to weather whatever it took to beat cancer and resume the life she enjoyed before her diagnosis. She tackled the chemo with everything she had, even though chemo lived up to the worst things we had heard. Stef struggled big-time with the nausea and fatigue, but never complained once.

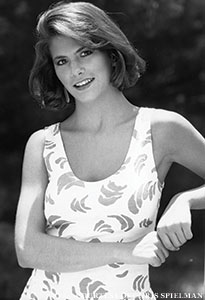

It took an emotional toll when her hair started falling out after her second treatment. The hair loss really traumatized her. The first time she walked into a wig store, she started crying. But then, in true Stef fashion, she seized control of the situation. One day, while she wrestled on the floor with Noah, he rolled over and came up with a mouthful of her hair. Right after that, she called her hairdresser. Stef didn't want chemo to take her hair. She would decide how she lost her hair, so she had her head shaved. Of course, Stef made it an event. The "Hair Picnic," she called it. The kids watched and ate peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches on the patio while Stef sat in a chair with a handheld mirror as the hair that helped her land modeling jobs all over the country and in Greece came off in bunches.

I intended to be there and see it all happen, but I arrived a little late. I was having my own head shaved in a sign of solidarity. I wanted to divert attention away from Stef. I wanted the kids to feel comfortable with how she looked. She wouldn't seem different to them if we both looked the same. I also wanted to show that whatever came our way, it couldn't defeat us as long as we stood together. So now we sported a matched set of bald heads. Stef wore hers like a badge of courage and so did I. We were teammates, right down to the skin on our skulls.

That night, Stef told the kids we would have a hat party. She tried on different hats and wigs and so did they. I took care of playing the music and making silly commentary, like a moderator at a fashion show. We tried to send the message to our kids that cancer couldn't destroy us. We could still have fun as a family. We could still laugh. Through tears, maybe, but we could laugh. After the party, Stef told me, "That was one of the best moments we've had as a family in our entire lives."

Those good times, though, did not outnumber the difficult times. The side effects of chemo accumulated and beat Stef down. The more treatments she had, the more drugs that went into her system, the worse the nausea and fatigue and other symptoms became. The fatigue proved disheartening to someone who had run three miles a day, five days a week, before her diagnosis. As if she didn't get poked and prodded enough at The James, I injected her abdomen four times a week with Neupogen, a drug to boost her white blood cell count. I hated doing that. Because of her firm commitment and determination to do everything she could to get better, she got mad at me a few times for hesitating.

Even so, Stef struggled with depression. Her inability to join us in things we previously had done together as a family really brought her down. When I took the kids to McDonald's or Chuck E. Cheese, Stef stood at the door, crying as we drove away. She wanted to go with us, but her body wouldn't allow it. She needed to rest. She also had "chemo fog," a condition that comes over time, which left her in a daze, not thinking clearly.

For that reason, we had only one serious what-if conversation about the future. She sat at the kitchen table one morning, feeling sick, while the kids ate breakfast and played with their toys. They paid no attention to us while we engaged in a very frank conversation, right there in front of them, about what might happen if Stef died. We had never really talked about that possibility before, but for some reason, we started talking about it that morning. Something seemed very natural about that. It was the most important conversation we ever had, and we had it over coffee while the kids ate their cereal. Stef and I could always talk to each other like that. I loved how I could be direct with her and she could be direct with me, and neither of us ever felt hurt when the other just said what they were thinking.

She didn't hold anything back that morning, but I kept one thing hidden from her. I think most men have a natural instinct to protect their wives and children. Because of that, I blamed myself for letting this thing -- this threat to my wife's life and our happy existence as a family -- into our lives. I knew that made no sense, but I couldn't stop thinking that I, as a husband and father, had allowed cancer into my house to threaten my wife and my children's mother.

My football background had ingrained in me that, no matter what I faced, I could out-tough it, out-physical it, or out-hit it. But finally I faced an opponent I couldn't control. It wasn't even a fair fight. I had no opportunity to compete on even terms with cancer, and I really struggled with that. My Christian walk lacked maturity back then and I focused on all my past sins. A twisted logic caused me to ask, "What did I do to bring this on us?" I knew better than to think of Stef's cancer as some sort of punishment, but sometimes my mind just ran wild, and those crazy thoughts occasionally took over. So while Stef had her battle with chemo, I struggled with misplaced guilt.

Looking back, I realize I also really struggled with submitting to God's authority. I didn't rebel and shake my fist at the heavens -- far from it! I ran to God for comfort -- but I still didn't submit. Instead, I tried to bargain with Him. I had conversations with Him late at night, long after everyone else in the house had fallen asleep. I would watch infomercials on TV just to kill time. Occasionally I would talk to God out loud about whatever came to mind.

One night, as I watched the Alien Wedge infomercial, I turned from my chair toward the couch after the guy in the infomercial hit a golf ball off the bed of a dump truck. "Hey, Jesus," I said, "I don't think You can hit that shot." Then I laughed and I imagined Him laughing too. "Yeah, I think I can," I imagined Him saying. "OK," I said, "I have a deal for You. You get me through this, and I'll take care of everything else. We'll call it even." By that I meant, "Heal Stef and I won't bother You with any minor crap."

Obviously, that approach fell far short of submitting to God and whatever He planned for our lives. I still thought, or hoped, I had some control over what remained ahead of us. Of course, I didn't have any control, which became very clear to me over time.

Skipping the 1998 season to care for Stef took me away from playing organized football for the first time since I became eligible to play Midget League when I turned nine years old. Most people who knew me figured I would flip out because I had the reputation -- among those in the NFL and outside the league -- of someone completely consumed with football. I earned that reputation because I cultivated exactly that image with how little I allowed people to see of me away from the game.

Although I loved my wife and family more than anything else, until the possibility of cancer taking Stef away from us hit me squarely in the face, football was my god. I'm ashamed to admit that, but I can't deny it. I received letters from teammates when I announced I wouldn't play in 1998. Most of them said how much it surprised them that I would give up football for anything. I rarely gave anyone the impression that anything else mattered more to me.

In fact, though, I didn't struggle as much with not playing as I did with the idea that I was no longer a football player. I had played football my entire adult life, so I had no other identity. Sitting out the last half of the previous season with my neck injury made it easier, but still not easy, to realize, Hey, this phase of my life may be over.

No matter how willingly I'd decided to sit out in 1998, at times I still felt conflicted. Sure, I wanted to be with Stef; but on game days I also really missed playing. It might not have bothered me quite so much if I had just removed myself from the game as much as possible, but I didn't do that. Instead, I bought extra TVs. I had one in the basement, one in the bedroom, one in the kitchen, one in the family room, and one in my weight room. On Sunday afternoons, I turned on every TV and walked around the house from room to room, watching the NFL. I grew so frustrated watching one game and not being able to play, that I'd walk into another room, where I'd see a different game. I did that from 1 p.m. to 7 p.m. every week. Why didn't I just turn the games off? I don't know. It captivated me, like a car wreck pulled off to the side of the road. I just had to watch it.

The Bills started 0=3, which made it even tougher. Whenever you sit out in football, it's miserable, whether your team wins or loses. If it wins, you think, They must not need me. If the team loses, you feel guilty and think, It would be different if I could play. I didn't have much contact with the Bills except for one visit to Buffalo. I drove up on a Sunday morning. I talked to a few guys in the locker room before their game against the 49ers. After kickoff, they introduced me over the loud speaker and the fans gave me a standing ovation. I loved playing in Buffalo. Bills' fans really appreciated an honest effort. I'd been there only a year and a half, but they knew I'd given them everything I had. Still, watching from the sidelines that day really stank. I hated it.

For a decade I had defined myself as an NFL player and for ten years before that I did nothing but dream about it. So it felt almost surreal to be watching — but unable to participate in -- something that had been a part of my life forever. And it went on just fine without me.

Later that fall, Stef and I visited Cincinnati to see her sister Sue and her family. I first met Sue when I attended her wedding with Stef, who was sixteen at the time. I wore my brother's too-tight sports coat and a pair of borrowed dress shoes, and I really felt out of my comfort zone. But I wanted to support Stef, meet her extended family, and wish Sue well, so even though I was an extremely shy, introverted kid who found that kind of social interaction very hard, I bucked up. I acted like I thought a man should act -- better, in fact, than I acted during this trip to Cincinnati. I happened to be watching TV when an NFL commercial came on. I stuck my fingers in my ears and started singing, "Na-Na-Nah-Na-Na-Nah," like a little kid who doesn't want to hear it's time to go to bed. I consoled myself with the knowledge that the extra time away would give my neck another year to heal.

When the 1998 season ended and I could start looking forward to playing again in 1999, it felt like someone had lifted a giant weight off my chest.

The Bills eventually made the playoffs without me, but lost in the first round on Saturday, January 2. Stef had her last chemo on Tuesday, January 5. We had looked forward to that day for so long that we wanted to celebrate. Now that it had finally arrived, we planned a trip to Disney World with the kids. One day at the park, as we waited for the Dumbo Ride, Stef smiled at me and said, "You know what? I haven't thought about cancer all day."

-- That's Why I'm Here is available through the publisher, Amazon, iTunes and Barnes & Noble. To learn more about fighting cancer, go to the website of the Stefanie Spielman Fund for Breast Cancer Research.

Excerpted by permission from That's Why I'm Here by Chris Spielman. Copyright (c) 2012 by Chris Spielman and Zondervan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- Kerri Walsh Vouches For Pregnancy Pilates

-- One On One With Michael Phelps

-- Memory Of Charlie Batch's Slain Sister Lives Through His Youth Foundation

-- Cubs Fans Walking 1,900 Miles With Goat To Fight Cancer, End Curse