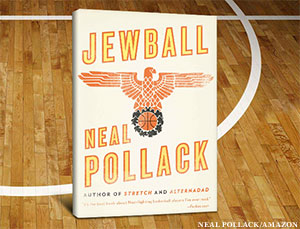

This excerpt is from "Jewball," a novel by Neal Pollack:

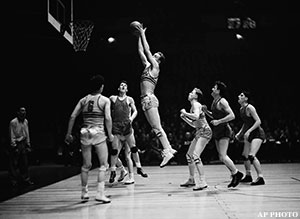

1937. The gears of world war have begun to grind, but Inky Lautman, star point guard for the South Philadelphia Hebrew Association, America's greatest basketball team, is dealing with his own problems.

His coach has unwittingly incurred a massive gambling debt to the Bund, a group of American Nazis. His main basketball rival is self-righteously leading public protests against homegrown American fascism. And his girlfriend wants him to join a Jewish student organization that's all talk and no action. It's more than Inky can deliver. He just wants to play ball and occasionally beat people up for money.

When the Bund comes calling for what it's owed, Inky has to make a stand for his ragtag bunch of teammates and the coach that got them into this mess. With the Bund closing in, Inky's game isn't just basketball anymore. It becomes a battle that pits Jewish pride against Nazi fascism.

The tides of history are flowing against a guy like Inky. Can he make his free throws and still make it through the season alive? Get ready. This ... is Jewball.

Every sooty phone pole in Jewish Philadelphia had a peach basket on it. Every alleyway was filled with the thwang of leather on asphalt or, in the less developed neighborhoods, the mellower sounds of leather on dirt. And every boy worth his bar mitzvah legacy wanted to play. On that day, the day when the world put his father's memory to rest for good, Louis "Inky" Lautman joined their number.

He came upon an alley. There, five boys (a couple around his age, the others older, and all taller than he was) were taking turns, and taking aim, at the basket. But they clearly seemed bored. Inky stopped and watched. He was many blocks from home. These boys wouldn't know him from Greenbaum.

The ball got away and rolled to Inky's feet. Inky stared at it as though it had just fallen from the sky.

"Hey, shorty!" one of the boys shouted.

"Me?" Inky said.

"You gonna give us our ball?"

"Sure," Inky said.

Inky picked up the ball. It felt smooth and worn, totally natural in his hands, like he was putting on his best pair of overalls.

"Throw it, you ass!"

Inky drew back the ball to his chest, crooked his elbows, and shot a decent-looking bounce pass down the alley. The boys looked impressed. Inky had no idea why.

"You play?" asked another boy.

"No," Inky said.

"You want to? We need a sixth."

"Okay."

"Why you wearing a tie?"

"My pop died."

"That's too bad."

"Yeah."

Inky stood there, looking into the alley. They threw him the ball. He didn't know what to do.

"Bounce it," said the kid.

Inky did.

"Again."

Inky loosened his tie and dribbled in. Within a minute, the tie was off and lying on a trash can lid. A minute after that, Inky was in his shirtsleeves. He played three-on-three, not very well. But the guys liked having him in the mix. He picked up the rules easily and he was fast enough. Inky had the instinct, even then, to pass the ball, to scrap, to dive to the ground, to put his kneecap where it shouldn't go. His team won the first game, and then they switched players. Inky got cocky. He started shooting a lot. But he had no technique and no accuracy. This time, his team lost. The seeds of a basketball lesson had been planted.

They played until the streetlamps came on, five hours or more, and then a little longer, until the kids' moms came out of nowhere and dragged them by their ears toward home. But no one showed to drag Inky home. No one ever would. The kids left the ball behind and Inky shot it until the moon shone over the rooftops, and then he shot a couple hours more.

From then on, Inky, untethered from adult supervision, spent his voluminous free time in every alley and on any playground he could find. He worked the leather. When he needed a ball, he stole one. When he couldn't find one to steal, he took money from his mother and bought one. He practiced shooting until his fingernails bled, and he dribbled until blisters bloomed on the heels of his hands. Often, he played pretty well. Even when he didn't play well, he played hard. He went from last picked to the middle of the pack. By the time a year had passed, they knew him in the alleys and were letting him act as captain of his own team.

He was never the fastest or the strongest or the best shooter; no one would ever say that Inky Lautman had the total package. He was too short and a little squat. But he didn't stop, he couldn't stop, it never even occurred to him, and by the end of any game, everyone knew that Inky was the court boss. Let the other players score, Inky said to himself. At the end of the day, he'd hold the keys.

Inky Lautman: born to run the point.

A reputation developed as Inky made the alley rounds. He got invited to play on actual courts. Compared with those tight spaces he'd started in, with their barely tolerable stench of rotting fish heads and discarded apple cores, playing on a hardwood floor and shooting at hoops with actual backboards seemed easy. He felt like a hobo who'd somehow inherited a mansion. Inky glided up and down the court with pure focus, seeing every opportunity and grabbing as many as he could. Any guy who happened to land on Inky's team knew that there'd be at least a chance to win that day.

High school came early at age thirteen, not because Inky had done anything of interest in the classroom, but because the team needed a point guard. The coach paid off the necessary school authorities, and Inky was in. So once again, he found himself just about the smallest guy on the court, and once again, his play dominated because no one hustled harder. The games had official clocks and official scorers and actual fans, including more than one girl who showed Inky a tantalizing flash of knee. With the fans came the boosters and the reporters, and for the first time, the Lautman name meant something in Philadelphia other than a drunk tank asterisk in the police blotter. By the middle of Inky's sophomore year, the gym was full for every game. A promoter wrote a song about him. "Hey, hey, Inky / The fastest Jew in school" went the lyrics. No one ever claimed it was a good song, and it left a slim mark on the culture of the town.

One night, after a typical game where Inky had scored twenty-two points with twenty-two assists, seven rebounds, nine steals, four fouls, and one technical foul for a knee to another player's groin, his eyes wandered up to the bleachers, where a flame-eyed gal was staring at him and running her tongue around her lips. Inky thought he might dip his toe. On his way up the stairs, destiny intercepted him, in the form of an overweight cigar chomper in his mid-thirties who was unimaginably sweaty all over even though it was barely March. Inky tried his usual dodge, but the guy didn't bite. No mere sophomore was going to get past that wall.

"Inky Lautman?" the guy said, extending his hand.

"Yeah?" Inky said, not extending his.

"Eddie Gottlieb," the man said. "So?"

"So I own the SPHAs."

"That's good for you."

"I haven't seen you around the Hebrew Association much lately. Or ever."

"I don't go in for the religion."

"I don't either. We've got the best courts in town."

"I do okay without the best courts."

"You do more than okay, kid. You've got the best basketball sense of anyone I've seen in twenty years."

"Yeah?"

"Yeah."

"Well, fuck you, Gottlieb. I got a date."

Gottlieb looked up at Inky's date.

"That broad?"

"Yeah."

"You can't afford her."

"Why not?"

"Because she's a hooker."

"And how do you know that?"

"Believe me," Gottlieb said. "I run a basketball team. I know a hooker in the stands when I see one."

"Yeah, well, maybe I can get something for free."

"That kind of defeats her purpose," Gottlieb said. "The more you think of yourself, the more she'll charge you. But I guess you need to learn these things on your own."

Inky brushed past.

"Hey, Lautman?" Gottlieb said.

"What?" Inky said. "What do you say I come by your house sometime

and meet your parents?"

"Ain't much to meet. My pop's dead and my ma might as well be."

"Sorry to hear that."

"It's a fact, that's all."

"Anyway, I've got a business proposition."

"What the hell does that mean?"

"It means you wanna play ball for the SPHAs, you dumb heeb?"

"Does it mean I have to play with you?"

"No, but it means you have to play for me."

"Maybe not, then," Inky said. Inky gave Gottlieb his address anyway.

Gottlieb looked surprised. He said that with an address like that, he'd better stop by before sundown, to increase his odds of ending his day alive. Inky told Gottlieb to go sit on a pole. They'd quickly figured out how to talk to each other.

Gottlieb showed up the next afternoon. Inky answered the door. When he opened it, dust swirled. The apartment smelled old.

"Guess you really need a point guard," Inky said.

"I might," Gottlieb said. "Guess you really need a maid."

"It's her week off," Inky said. "Make it quick. I got practice in half an hour."

"Is your mother at home?"

Inky shouted toward the back of the house. "MA! We got company!"

Ma Lautman staggered out of the back, where she'd been boiling onions even though she didn't plan to eat them. By now, she had the look and demeanor of a stygian witch, complete with rags. She appraised Gottlieb up and down.

"Why are you so fat?" she asked.

"Because I like to eat," Gottlieb said.

"Ma," Inky said, "this is Mr. Gottlieb. He wants me to play basketball for the SPHAs."

"What are SPHAs?"

"The South Philadelphia Hebrew All-Stars, Mrs. Lautman," Gottlieb said. "It's a professional basketball team."

"They're the best team there is," Inky said.

Gottlieb looked surprised. This was the first sign of enthusiasm he'd seen Inky show about anything. No fifteen-year-old should have been able to keep his cool at such a prospect. Maybe the kid was normal after all.

"Professional basketball," Mrs. Lautman said. "Does that mean you get paid?"

"I pay my boys well," Gottlieb said. "Meals and travel too."

Ma Lautman pondered this for a few seconds. She turned to her son.

"Inky," she said, "is this what you want to do?"

"I don't know," he said.

She turned to Gottlieb.

"Is he any good?"

"Oh, he's very good," Gottlieb said.

"Damn right I'm good," said Inky.

"But he can get better."

"No thanks to you."

"You should do it, son," Ma said.

"Okay, Ma," Inky said.

Gottlieb pulled out Inky's contract. The timing was good for Inky, because six months later, people would be jumping out of Manhattan skyscrapers. At such times, it was good to have steady work.

"I need you both to sign," he said. "Inky's underage."

"Sign what?" Ma Lautman said.

"Inky's contract," said Gottlieb.

"Contract for what?"

"For playing basketball."

"Inky doesn't play basketball," said Ma. "He's just a baby."

Inky moaned with frustration. Gottlieb felt less like a basketball coach and more like a charity worker. But at least he had himself a point guard.

Within a month, Inky was playing professional basketball. By the following month, he had his pick of girls from the stands. He didn't have to pay for any of them, though some of them were fairly nice girls and wanted dinner first. But girls weren't the only ones watching Inky. Everyone paid attention to the show- runner, the tough, no-bullshit guy at the center of the action. Inky didn't care. His early years had given him a hard, mercenary approach to life, and it showed on the court.

The Depression hit. Fascism in Europe followed. Inky had a job and didn't care for politics. He figured everyone was just looking for a cut of whatever action they could generate. So he just kept playing basketball. This made Inky the perfect mark for a certain type.

One night in the winter of 1935, a man came up to Inky after a game. He had pale cheeks, a thin mustache, and little round spectacles. The games had been attracting all kinds of customers.

"Mr. Lautman?" the guy said.

"Yeah?" said Inky.

"My name is Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze. I represent an organization."

"So?"

"I enjoyed your game tonight."

"What's that to me?" Inky said.

"Maybe a lot."

"Get to the point," Inky said, pointing at a hot number powdering her nose in the stands. "I got a date."

"Okay, I will."

"Not quick enough."

"How'd you like to make a little extra money?"

Now Inky was listening.

-- Neal Pollack is the author of the cult classic The Neal Pollack Anthology of American Literature, the novel Never Mind the Pollacks, and the memoirs Alternadad and Stretch: The Unlikely Making of a Yoga Dude. A graduate of Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, he is a frequent contributor to the New York Times, Slate, Salon, GQ, Vanity Fair, and Maxim. He lives with his wife and son in Austin, Texas. Click here to buy "Jewball" on Amazon.

Copyright (c) 2012 by Neal Pollack. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- 25-Year-Old Cubs Fan Lives The Dream As Wrigley Field Announcer

-- The Hottest New Running Trend

-- Jeremy Lin: His Impact On Changing The Perception Of The Asian American Male

-- Coregasm Phenomenon Is Confirmed By New Scientific Study