Delray Brooks sat alone in the lobby of Heroes Camp, a center for under-privileged youth in South Bend, Ind., watching his past and the present come face to face.

He remained fixated on the television set that operated like a time machine, transporting Brooks back 25 years when life was good and free of the peaks and valleys that have defined his unsettled existence ever since.

A passerby would stop occasionally to ask Brooks the score and move on, likely unaware of the personal connection the 46-year-old volunteer coach shared with the Louisville-Florida Elite Eight showdown he couldn't take his eyes off of, with one school punching its ticket to the Final Four in New Orleans.

In 1987, Brooks had been in New Orleans, at the Final Four, attempting to write the final chapter of the kind of fairy-tale story typically celebrated annually during the NCAA tournament.

His coach at the time was Rick Pitino and his teammate at the time was Billy Donovan -- the two men that Brooks was watching on television in the lobby of that Indiana youth center all these years later.

The more he watched, the more the uncomfortable tension Brooks had inside him all day grew. As much as another "Pitino the professor vs. Donovan the pupil" storyline had developed, the emotional ties Brooks had to both men left him unsettled.

Someone had to win. Someone had to lose. Two opposite ends of the spectrum Brooks has lived on since his own New Orleans experience 2½ decades ago. Despite the discomfort he was experienced as Louisville ended Florida’s season, Brooks kept watching.

Basketball, as it had so many times before in life, was bringing Delray Brooks full circle.

The condensed version of Delray Brooks' basketball career reads like this: Indiana Mr. Basketball. USA Today National Player of the Year. Played for Bob Knight at Indiana. Played for Rick Pitino at Providence College. Four Final Four appearances, one as a player, three as an assistant coach -- again with Pitino -- at Kentucky. One national championship.

All good, right? Not so fast.

Hired to rejuvenate a troubled basketball program at the University of Texas-Pan American. Fired after being suspected of embezzling $25,000 of school funds, capping a two-year stretch when his team lost 46 of the 54 games it played under Brooks' watch. Struggled to land a coaching job before returning back to Indiana to start the varsity basketball program at a prep school near his hometown. Arrested for a probation violation stemming from his first run-in with the law.

At times, the Final Four run to New Orleans with Providence in 1987 seems like yesterday. At others, it is a page in a living scrapbook that's been covered with many more pages filled with images -- both good and bad -- ever since.

"There's been some incredible highs and there's been some lows, some valleys in that time," Brooks says. "But through it all, I've always been able to stay strong and say strong in my faith and continue to believe in myself and believe that there's always something better for me.

"But it's been a roller coaster ride the last 25 years."

By the time Delray Brooks graduated from Rogers High School in Michigan City, Ind., in 1984, he was a national commodity. He averaged 33.4 points and 7.3 rebounds a game as a senior, leading Rogers to a 28-1 record, losing only to eventual state champion Warsaw in the state playoffs.

He shared Indiana's Mr. Basketball Award with Troy Lewis, who would go on to play at Purdue. Brooks -- one of two high school players along with future Kansas star Danny Manning to try out for the 1984 Olympic team -- landed in Bloomington playing for Bob Knight at Indiana.

Brooks could have played anywhere, but chose Indiana, where Knight had led the Hoosiers to a national championship three years earlier. Brooks saw significant time as a freshman, averaging 15 minutes a game, scoring a career-high 16 points against Minnesota, emerging as the up-and-coming star he expected to be despite seeing his playing time diminish and averaging only 2.4 points by the end of his freshman year.

Heading into second season, Brooks was expected to be Indiana's top reserve, backing up guards Steve Alford and Stew Robinson. But as a sophomore, his time on the floor yo-yoed, playing integral role in Knight's plans on some nights and barely moving from the bench on others.

Knight constantly harped on Brooks' defensive footwork, which he kept telling the young guard was too slow to fit into man-to-man system. Despite his ability to score, the fact Brooks would sometimes get lost on defense irritated Knight to no end.

While some of Knight's players could handle the coach's profane outbursts and personal attacks, Brooks couldn't.

"Delray is a really, really nice guy and I think the constant battering you took to play for Knight wore on him," says John Feinstein, who spent a year inside Indiana basketball for his best-selling book, "A Season On The Brink."

"There kids could do it, but then there were plenty of guys who just couldn't take it. I don't mean couldn't take it in the sense of not being tough, but couldn’t take it in the sense of just being human."

Brooks was clearly one of those players. Soon, the frustration of not playing and the constant abuse he took from Knight became too much. Discussions began between Knight and Brooks' father, who maintained Brooks wasn't playing as much as he should.

After playing sparingly in Indiana's first two Big Ten games -- including only four minutes in what would be his final game against Michigan State, Brooks decided enough was enough.

"I was there sitting on the bench watching others guys play that I had out-played forever and that was the toughest thing for me," Brooks says. "I could have gone to any school in the country and I found myself at Indiana sitting.

"That was tougher than anything else."

Brooks contemplated where to go next. His first choice, Notre Dame, didn't accept transfer students. NCAA rules prohibited him from accepting a scholarship from other Big Ten schools.

He finally settled on Providence in 1986, finding a basketball home and a coach in Pitino that he was destined to play for.

Brooks and Pitino first met when Brooks was 13 at Five Star Basketball Camp. From their first meeting, Brooks sensed something special. He looked forward to the next summer when he could learn under Pitino; a coach Brooks would first play for and then coach under.

As talented as Pitino knew Brooks to be, the young coach also was concerned about his new guard's psyche. Brooks was a tenacious defender and a proven scoring, but Pitino worried about how Brooks' diminished role and subsequent departure from Indiana would affect Brooks while trying to adjust to new surroundings.

Feinstein says there was no surprise Brooks transferred, given the toll Knight's constant prodding had taken.

"With people who don't or didn't succeed under Knight, it was usually more about personality than it about playing style," Feinstein says. "Knight had a unique way of both making players respond and making them not respond.

"The kid I saw in his last days at Indiana was a kid whose confidence looked shot to me."

It didn't take long for Pitino -- another hard-nosed coach who expects perfection from his players -- to notice the toll playing for Knight took on Brooks. Brooks claims he never doubted himself and that he never struggled with the emotions of trying to meet expectations, but Pitino -- especially early on in working with Brooks -- saw something different.

"When he came to me, he had an extremely low self-esteem and he needed to be brought up emotionally," Pitino says. "With self-esteem, you have to earn it and deserve it before you can feel better and Delray had to earn it.

"He had to get in the gym and improve his game, work on his ball-handling and we had to get him to the point where he thought he was a good shooter again. Once he did that, it was easy to raise his self-esteem."

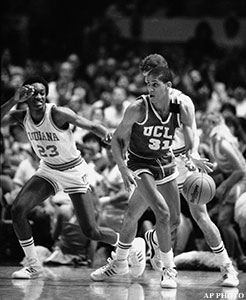

Pitino describes his 1987 Final Four team (shown at their 25th-year reunion, left and below) as a collection of players who needed to work to feel better about themselves. He motivated each player differently, understanding that over time, the team would come together.

Pitino ran his players hard. Before the NCAA placed time limitations on how long teams could practice and before it required coaches give players a day off, basketball workweeks were grueling. Brooks estimates Pitino had his players in the gym between 60 and 80 hours a week.

"We worked harder than we had ever worked in our life on anything," Brooks says. "It was just incredible, but we got to see the results of our hard work."

After losing to Georgetown in the Big East tournament, Providence was seeded sixth in the Southeast Region in the NCAA tournament. The Friars toppled Alabama-Birmingham and Austin Peay before upsetting No. 2 seed Alabama sparked by Donovan and Brooks, who combined for 49 points.

That set up a regional championship meeting with top-seeded Georgetown, which had won two of its two three games with Providence that season.

By that point, Providence brimmed with confidence. One win away from New Orleans, the Friars staged another upset, knocking off the heavily favored Hoyas by 15 points.

The victory sent Providence to the Final Four, where Brooks' past and present would meet. The presence of Indiana, which would go on to beat Syracuse in the national finals on Keith Smart's last-second jump shot, made for an awkward reunion for Brooks.

Brooks had never regretted his decision to leave Bloomington, but never expected he would share the national stage with his former teammates so soon after he left. He walked down Bourbon Street, where Providence and Indiana fans greeted him alike.

Brooks was too young to appreciate the irony of leaving one school for another just to both reach the Final Four.

"It was just a weird set of circumstances," Brooks remembers. "It wasn't like it was even two years (after leaving Indiana) -- it was the next year. But (leaving) was a decision I had to make at the time and it ended up being a good decision.

"But it was a decision I had to make for me."

Decisions in life would prove equally challenging.

Brooks finished his Providence career in 1988, leading the Friars in scoring. Undrafted to the NBA, Brooks played in smaller professional leagues, finishing with the World Basketball League's Florida Jades as a player/team executive before reuniting with Pitino as an assistant coach at Kentucky.

In six years in Lexington, the Wildcats reached the Final Four three times, winning the national championship in 1996.

Brooks wanted to run his own program. He was hired at Texas Pan-American in 1997, taking over a program that had experienced its share of troubles before Brooks' arrival.

In 1996, the school was stripped of its NCAA certification after two assistants were alleged to have helped recruits with correspondence work. Before the 1997 season, the program was given conditional certification, leaving Brooks to rebuild.

Two years later, Brooks was alleged to have misused university money after $25,000 from a game guarantee from Southwest Missouri State ended up in Brooks' personal account.

School officials charged that Brooks then made withdraws from the account for personal use. Brooks denied wrongdoing but acknowledged the money had ended up in his account although he claimed he didn't know how it had gotten there.

Brooks was later indicted of the charges by a grand jury. He pleaded no contest and was sentenced to 10 years probation with the condition that he pay full restitution in the case.

Things continued to unravel from there.

His mother lost a battle with breast cancer and passed away. Within a short time, his brother-in-law and mother-in-law passed away. It wasn't long before circumstances became too stressful on Brooks' marriage, which ended shortly thereafter.

For as many peaks as Brooks had reached throughout his basketball career, his first coaching job and the events that followed forced Brooks to bottom out.

Brooks was left to rely on friends, family and a faith that was suddenly being stretched far more than at any other point of his life.

As hard as life hit him, Brooks refused to give in, falling back on advice his father had passed down early in his life.

"I never felt like I lost everything I worked for," Brooks says. "I knew (life) wasn't always going to be easy and there are going to be bumps in the road. It's about how your respond, it's how you get up after you’ve been knocked down.

"There were difficult days, but you just had to stay strong."

Harold Starks, a former Friars guard whose career ended just as Brooks was arriving at Providence, was among those Brooks depended on.

The two talked regularly, rarely getting into the details of Brooks' struggles, but instead, simply just remaining in contact.

Brooks and Starks had become close friends more than 10 years before, and although Starks couldn't fully understand everything his former teammate was going through, he did what he could to be there for Brooks.

The more Brooks hurt, the more Starks felt his pain. Despite spending only a short time together at Providence, the two became like brothers.

Starks encouraged Brooks to keep pressing forward.

"I think a lot of that just comes from being an athlete," Starks says. "You go through trials and tribulations on the court, you may lose a starting spot, you may have a bad year, but you keep going.

"You keep practicing and you keep thinking, 'There's going to be another game, I'm going to get a win. I'm going to get on the right track.' As an athlete, it's always about getting back in the gym."

After being fired at Texas-Pan American, Brooks spent the next three years fighting to keep his career going. He applied for countless number of coaching jobs, reaching out to colleges around the country, hoping someone would give him a chance.

Each inquiry ended the same way. He would receive a letter or a phone call thanking him for his interest. Brooks' prideful side was convinced his notoriety within basketball circles led to the courtesy calls he received. His realistic side reminded him why no one was willing to hire him.

There were days when disappointment and doubt clouded his optimism. He kept telling himself a great opportunity was right around the corner and that better days weren't far off.

But some days weren't as good.

"There were times I wondered if my best days were behind me," Brooks says. "But you can't live your life like that."

Brooks' faith helped him persevere. As much as those around him convinced him to leave basketball behind and pursue other passions, basketball remained the constant that kept pushing him forward.

As painful as the journey had become and has patient as he had to be until his next coaching opportunity presented itself, Brooks (shown clowning with Donovan at Providence's 20th-year reunion) kept reminding himself to be faithful to himself.

"I finally came to the point where I knew I wasn't going to run from the game, I'm not going to fight the game," Brooks says. "It had become obvious that God wants me to be part of this game."

Brooks' journey took him to Florida, where he coached high school basketball and then to the West Coast, where he helped run the Southern California Basketball Academy before returning home to Indiana.

The constant search for work began to take its toll. Brooks had nearly convinced himself that he would find work elsewhere, beginning to think that perhaps, coaching had passed him by.

Family members pressed Brooks to pursue an opening at La Lumiere School, a prep school in LaPorte, Ind. His high school coaching experience in Florida hadn't been what Brooks expected, turning him sour on coaching at that level.

Against his better judgment, Brooks applied and was hired, starting five years at the school, which became a basketball breeding ground that sent players onto college programs.

He sent his players onto schools like Northwestern, Purdue and Valparaiso, allowing him to use his passion for basketball and teach in a way he had always hoped.

Still, in the good times, there were struggles.

In 2006, Brooks was arrested for probation violation stemming from the incident at Texas Pan-American. Brooks was charged with not paying restitution in the case, creating another obstacle for him to clear.

La Lumiere headmaster Michael Kennedy had hired Brooks because he was a winner. Ultimately, he stood behind the former high school and college star, allowing Brooks to remain at the school before he left in 2010.

Life since has taken Brooks away from basketball -- if only temporarily. He continues to work on real estate business interests in California, and in February, interviewed with ESPN to become an in-studio personality and game analyst.

He will audition for a job in late April, again facing the possibility of being around college basketball on a full-time basis, albeit in a different realm. (If he gets the job, Brooks would technically become Knight's colleague.)

Since leaving coaching two years ago, Brooks, who now lives in South Bend, has remained connected with the game that made him a household name not only in his home state but across the country.

He attends games and practices and volunteers at the Heroes Camp, passing his knowledge onto kids that may not otherwise have the opportunity to learn.

"It's just been different for me not to have to go to practice every day," Brooks says. "Could I do that again? Sure -- in a heartbeat. But I'm looking forward to the challenge of being able to call a game and present it to an audience and be informative and entertaining at the same time."

He will spend Final Four weekend at home with his children this weekend, reliving memories of his own New Orleans experience 25 years ago.

A week after watching his former coach and his former teammate fight for a Final Four berth, Brooks with watch three games this weekend with a different level of allegiance.

He will watch Pitino coach Louisville against overall No. 1 seed Kentucky, again connecting Brooks' past with the present.

Having been part of four Final Fours himself, Brooks will allow himself to reflect on his past and what the NCAA tournament has meant to his life. But he will do it with a new appreciation for what's happened since 1987, and how he has managed to survive the roller coaster ride that he has endured the past 25 years.

Life now, like then, is good. With prospects for a new broadcasting career and an upcoming wedding in June, Brooks has again found happiness despite not perhaps now following the path he believed he would.

He has learned to be patient, passing on one chance to wait for a better opportunity to come along. Life -- both in good times and bad -- has taught him one lesson after another.

And through hard work -- like those grueling weeks in the gym at Providence with Pitino -- Brooks' efforts to make the most of his talents have paid off.

"I'm just at a real good place spiritually and with my family and I'm just in a real good place," Brooks says. "That's the best way I can describe it."

And sometimes, as life has taught Delray Brooks, that's more than enough.

-- You can email Jeff Arnold at jeff.arnold@thepostgame.com and follow him on Twitter @jeff_arnold24.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- School In Senegal Is Well Represented In NCAA Tournament

-- Adventure Races Sweeping The Nation

-- The Hottest New Running Trend: Bandit Racing

-- World's Tallest Basketball Player Dunks With Worst Vertical Ever