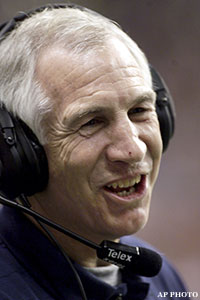

One of the most surprising developments in the Penn State scandal came well after the arrest of former assistant coach Jerry Sandusky. In many sex abuse cases, a backlash against possible victims causes a swell of fear. Would-be supporters think twice, and other victims get wary. One high school student in this case, Victim One, reportedly had to transfer because of bullying. Yet stories of abuse within and beyond Central Pennsylvania continue to emerge. Sandusky's appearance on NBC only emboldened more alleged victims to talk.

And last week, allegations of a new and separate college sports sexual abuse scandal surfaced at Syracuse University. Two former ball boys for the university basketball team, now grown men, are accusing assistant coach Bernie Fine of sexual molestation. Head coach Jim Boeheim is standing by Fine, who maintains his innocence.

We don't know whether the timing of these distinct allegations have anything to do with the Sandusky scandal. But we might be experiencing the beginning of a cultural shift in the way we view sexual assault cases. In a hauntingly beautiful Slate column Sunday, Notre Dame law professor Mark P. McKenna revealed how the Penn State story has brought up painful memories of his own sexual abuse by a coach connected to a college football team. Rape and abuse victims flooded the inbox of ESPN columnist Rick Reilly, opening up to him with their own stories. Victims seem to be experiencing a catharsis of memories they've been forced to hide in the darkest parts of their mind.

What will it mean for the future? Does the rally of support for the alleged victims mean we are more open to hearing similar stories? Will law enforcement approach these cases with more vigilance? And will victims and whistleblowers feel more confident challenging the institutions that may value positive PR over responsibility?

"When a story like this goes national, I do think more people will be inclined to come forward in the future," says Adam Loewy, an attorney in Austin, Texas, who has represented children who were sexually abused. "The more reports that get out there, the more likely people are to come forward."

Colleges can be insular places where tradition and loyalty can trump objective evaluation. Employees often climb the academic ladder by fostering relationships with both colleagues and superiors. Sandusky began his Penn State career as a football player. Former senior vice president Gary Schultz put 40 years into the university. Former athletic director Timothy Curley attended Penn State and worked his way up to an executive position. Joe Paterno, of course, coached for 46 seasons. When all those people have been around so long, who will call them on questionable behavior?

Apparently, no one. And that's the problem. Faces are so familiar that the faceless are doubted.

"First, the institution denies the allegations," says Loewy. "Then the circle the wagons when they realize something really might have happened. Then, they try to distance themselves, throwing the person under fire to the wolves while they scramble to get their PR together."

There is a federal law that is supposed to keep these cover-ups from happening on college campuses. The Clery Act took effect in 1990, requiring universities that participate in federal financial aid programs to keep records of and report every crime that happens on or near campus. Schools can face fines of up to $27,500 per violation, but that's nothing to a college rolling in endowments. Clearly, this potential fine was not enough to push leaders at Penn State to go to the police.

The law has serious shortcomings, even beyond the severity of its penalty, says Steven Janosik, department chair of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at Virginia Tech.

"For these data to helpful, the Clery Act should require that college administrators use the same metric that the FBI and state police use when they report criminal activity -- that is, the number of incidents per 100,000 in the population," Janosik says. "If we reported campus crime in this way, folks would have a much better understanding of what the risks in the community really are."

Although the law may help students and faculty on campuses make better decisions, it doesn't do much to prevent crime. A serial rapist went undetected for three years at Texas A&M University before winding up in state prison, although he still denies the charges. At Tarleton State University, it took a journalism professor, his tenacious students and open records requests to reveal that the university had systematically underreported sex offenses, drug violations and burglaries. According to The Center for Public Integrity, offenders repeat sex offenders have been caught at Indiana University, Towson and the University of Colorado at Boulder. But that came after they'd already severely damaged the lives of other students.

"As with most laws, the more enforcement, the more campuses will truly embrace the Clery Act," says Allison Kiss, executive director of Security on Campus, an organization dedicated to promoting the Clery Act. "One intention of the Act is to truly institutionalize campus safety. University and campus police cannot do it alone; campus safety needs to be a community responsibility."

For the law to be effective, the entire institution must embrace accountability. Kiss says she's seen discussions among members of Congress about reviewing the existing laws, and expects the Jerry Sandusky case to be a catalyst for hearings in the future.

The outcome of Sandusky's trial could help victims feel freer to come forward and receive more public support. But as Janosik says, we just don't know yet. This case, as Loewy points out, is "egregious." Future situations where the evidence is less sound may devolve into the kind of he-said, she-said that often provides a chilling effect to rape victims both young and old.

"If those who failed to act and those who committed criminal acts are punished commensurately for their wrongdoings, victims might feel the system might work for them and they might feel safer about making the decision to come forward," Janosik says. "If those who are responsible receive light treatment, such a result would surely have the opposite effect."

The good news is officials at some universities are looking hard at their response procedures after what happened at Penn State. But for abuse victims and witnesses to feel safe and protected, universities must build a new tradition of transparency and accountability.

That's hardly a sure bet.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- Years Before Penn State, Red Sox Had Similar Sex Abuse Scandal

-- Explaining Penn State Scandal To My Dad

-- Video: Dad Is Red Sox Fan Who Won't Let His Son Root For The Yankees

-- College Basketball's Dad-Son Coach-Player Duos