Hockey?

To Popeye Jones this had to be a phase. His sons wanted to play hockey? At first he smiled when the subject came up after he returned home from an NBA season away. Sure, he liked watching hockey and he noticed that the neighborhood children played it outside their suburban Denver home. But he was an NBA basketball player, after all, a forward well into an 11-year career. Didn't basketball players' kids want to be basketball players too?

He looked at his three sons, amazed.

"You want to play ice hockey?" he asked.

They were standing in the middle of a sporting goods store, more than 10 years ago now. All around them lay piles of skates, sticks, helmets and sweaters. His credit card was out, the register was buzzing. Suddenly he felt an anger welling inside. He had a certain cache in being Popeye Jones. He was a 6-foot-8, a power forward, not a superstar but known enough to be recognized wherever he went. Now his kids were telling him they wanted to become hockey players?

How did they even learn how to skate?

Popeye chuckles at the memory. He's had time to adjust. His oldest son Justin, 20, just finished a season with a junior team near his Dallas home called the Texas Tornado. His youngest boy Caleb, 14, is showing promise too. But it is his middle son, 16-year-old Seth, whom hockey people are talking about. They say Seth, a tall, rugged defenseman who plays for the U.S. Under-17 team, might be a top 10 pick in the 2013 NHL Draft.

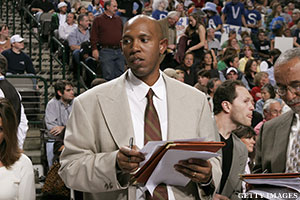

Popeye doesn't know much about hockey, not like basketball where he is an assistant coach with the New Jersey Nets. Over the years, he has stood in the back of rinks, a giant of a man trying to hide as he watched his sons skating across the ice. He calls out encouragement. He has learned the game but not enough that he can break down their performances.

Once, at the Pepsi Center in Denver, he bumped into Joe Sakic of the Colorado Avalanche.

"My sons want to play hockey, what do I do?" he asked.

Sakic stared at the man towering before him.

"They'll probably be big," Sakic replied.

Popeye can tell Seth is going to be very good. It doesn't take the trained eye of a hockey expert to realize he has skill. He's a defenseman, 6-foot-3, 185 pounds, physical but not intimidating. When Popeye watches Seth play, he sees a leader. The first word that comes to mind is "intelligent." He glides with purpose, weaving through players, never firing the puck too hard or too soft.

"When he's playing I see a calmness," Popeye says. "I see the ability when he is on the ice that more often than not he will make the right decision."

Or as his ex-wife Amy, the mother of his three boys says: "Seth sees things the others don't."

At USA Hockey they love Seth. The coaches there notice the same things that are so obvious to the father. The Under-17 team coach, former NHL player Danton Cole, calls Seth "a point guard."

"When it needs to go fast he speeds it up," Cole says. "When it needs to go slow he slows it down. His poise and maturity are an interesting combination. He's a tremendously mature young man as well."

Cole pauses.

"That kid was born to play hockey," he says.

Any hope Popeye had of converting his middle son to some other sport died soon after Seth first started playing hockey at about age five. When Amy realized the children loved the game, she took them for skating lessons. After that Seth wanted nothing more than to be a hockey player. Popeye tried to get him to fall for another game. There was basketball, of course. And when Seth turned out to be left-handed, Popeye -- who grew up playing baseball in addition to basketball -- thought maybe he could make his boy a pitcher. No chance. Seth wanted hockey.

"Since I started playing this is what I have wanted to do," Seth says. "It's just the speed and the intensity of the game."

He is in Ann Arbor, Mich., when he says this by phone. He moved there over a year ago when the U.S. team called, leaving his mom and his brothers behind to live with a host family and attend high school far away from the suburban Dallas home where his family relocated a few years ago. It is a lonely life in a way. "A different life," Seth calls it. But it might also be the greatest gift his father could have provided: An ability to focus completely on a sport, locking himself into it for weeks, even months at a time.

Through the years, Popeye brought his children around to the practices and locker rooms and games of whatever team he happened to be with at the time. From a young age they all noticed how it was a job to the players, how they had to work for hours lifting weights and practicing jump shots. It wasn't lost on Seth, for instance, that Mavericks forward Dirk Nowitzki took hundreds of jump shots alone in an empty gym just to be able to make 10 in a game.

Basketball took Popeye away for months at a time. For a few years, whenever he changed teams, the family moved along, following him from Dallas to Toronto to Boston and eventually Denver. When he signed with the Washington Wizards in 2000, they stayed behind in the Denver suburbs. Popeye played in Washington and moved back when the season ended. That's when the hockey started.

Popeye and Amy agree this is the way it had to be. Basketball was not something Popeye could fake and the nomadic life of a basketball player bouncing from team to team does not give the children a stable life in which they could stay in the same schools or keep the same friends. When hockey came along, everyone in the family says, it was Amy who had to drive the boys to practice, sit for hours in frigid rinks watching workouts and games until she could detect flaws, and tell her son about them the moment he was off the ice.

Asked if Popeye was the kind of father who came to games, yelling at the referees and harassing the coaches, Seth laughs. No, he says. When his father came, he'd stay in the back, out of the way. It was his mother who yelled. "She's been a great role model," he says.

But, of course, the story is always about Popeye because this is something most people can’t believe. In some ways it is a racial thing. Popeye Jones is black and while there have been more African American hockey stars in recent years, it is still seen as very much of a white game. With Popeye being so visible, a man most people have some kind of mental picture of, the fact his boys play hockey can create mild confusion.

"A lot of people do double-takes," Popeye says of his trips to the rink.

Amy is white, however. And maybe because of this and the fact the children were so good, the comments that might have been made in the past have never come up. Almost nobody makes mention of Popeye on the ice. Cole says he noticed Seth was asked a lot by the U.S. teammates and officials about his famous father. He answered the questions and then the conversation went somewhere else. "That's only going to go so far in a locker room," Cole says.

Popeye has a lot of funny stories about the cultural divide between his life and his sons. He remembers returning home from his seasons away and sitting down to watch basketball playoffs on television only to be overruled by his wife and kids determined to watch hockey. “I got banished to another room to watch basketball," he says.

Jokingly he blames Mike Modano. It was Modano, the former Dallas Stars center who first invited him to a hockey game after they met at a charity function when Popeye was a young player with the Mavericks. Popeye brought his wife and young children. They had so much fun, he remembers they kept going back. Maybe if he had never met Modano, or if they had never gone to the hockey game, things would have turned out differently. His boys would be playing basketball or baseball -- something he understood better.

Mostly, though there is pride mixed with a father's regret of a life lived on the road. So much he missed.

"It tore at my gut to not be able to see him on the (U.S.) team," Popeye says.

His salvation came from a video company who has an office in the Nets training facility. The company can make a DVD of any game that has been televised anywhere and it found many of Seth’s games for Popeye, burning a recording on a disc and leaving it on his desk for him to watch later. Last year, when the Youth 17 Championships coincided with a Nets game, Popeye found himself sitting in his hotel room at 2:30 a.m. watching recordings of the hockey, amazed by his son's poise and maturity.

He realizes Seth is so different than himself at that age. At 16 Popeye didn’t even know he wanted to be a basketball player. He played baseball and football in addition to basketball and loved them all. The fact Seth is so devoted to one thing amazes him.

"I know Popeye misses being around it," Amy says.

But this was the price of a life in basketball, a life that despite the long gaps also gave their children advantages others never had. The children never wanted for much outside of hockey, but there was always money for equipment and rink rental and lessons along with those trips to the NBA locker rooms and the understanding of how much you have to sacrifice to become great.

It's all worked out for the best.

Except Popeye still has this one thought. Every time he watches his son on the ice it won't go away, nagging in the back of the coach’s mind. Seth is so tall, so smooth, so in control ...

"I still think he'd make a great basketball player."