The greatest pitcher nobody has ever heard of is buried in section 7, lot 1, row 17, grave 97 of Burr Oak Cemetery, where for more than 30 years, barely a soul knew about the man resting in an unmarked corner grave, his story buried alongside Chicago trumpeters and outfielders.

Then he had a visitor.

The first time Peter Gorton walked onto the cemetery grass, he couldn’t escape forgotten feelings of indignity. He was drawn to this quiet parcel of land and the history beneath his feet, and for years, unearthing this man’s memory has motivated him. They have little in common, but when the white 41-year old workaday dad and weekend ballplayer discovered the black left-hander who pitched his way into folklore a century ago, he found his baseball calling. Here rests John Donaldson, and nobody remembered his name.

“THE GREATEST COLORED PITCHER IN THE WORLD"

There was a time when John Donaldson was as famous as Satchel Paige. He was heralded as the “famous colored twirler,” whose only crime was playing his best years before 1920, when the Negro Leagues were officially created. Not only did Donaldson miss his chance to pitch in front of large crowds, he missed the chance to cement himself into contemporary baseball history. The pitcher who won more than 350 games and had 4,500 strikeouts has largely been lost to time.

In the days before black baseball became the economic force that motivated white baseball to integrate in 1947, Donaldson was one of its original stars. Newspaper accounts compared his change-up to that of Christy Mathewson and his fastball to that of Rube Waddell -- both dominant pitchers of the 1900s. In the early years of black baseball, Donaldson was a trailblazer for the trailblazers. And because he played his best baseball in small towns instead of big cities, he faded like his change-up.

Donaldson became famous when he pitched on diamonds carved out of farmlands in the Midwest, in front of fans sitting on picnic blankets and on the hoods of Model-Ts. Donaldson pitched off shoddy mounds and perfected a high arm angle, so that his fastball roared down a fearsome slope. The local bush leaguers had never seen anything like him before. He left thousands of strikeouts behind him.

Almost 30 years after Donaldson was laid to rest, Gorton, a Minnesota native, began hearing stories in small-town Minnesota about a smoke-throwing left-hander from the Negro Leagues. Armed with a passion for baseball and a strong sense of history, Gorton visited a historical society in Bertha, Minn. where he got his first look at Donaldson, on a yellowing advertisement for the pitcher’s barnstorming troupe:

JOHN DONALDSON; GREATEST COLORED PITCHER IN THE WORLD.

What Gorton discovered next changed his life. When he asked the curator if he could take the poster off the wall for a closer look, he noticed a familiar face -- himself. Beneath Donaldson’s feet was a photo of the 1987-88 District 24 Champion Staples Fighting Cardinals High School basketball team. The gangly Gorton is fourth from the right, almost directly below the face of the greatest pitcher nobody has ever heard of. Donaldson hadn’t been under Gorton’s feet – Gorton had been under Donaldson’s nose.

“Right then and there, I was tied to it,” Gorton says. “I felt from that day there was something I was drawn to.”

"IF I ACT THE PART OF A GENTLEMAN, AM I NOT ENTITLED TO A LITTLE RESPECT?”

Gorton discovered fans had once loved Donaldson, who was born Feb. 29, 1892 in Glasgow, Missouri, a small town near the Mason-Dixon line. Donaldson sprouted into a physical powerhouse with a positive demeanor whose options did not match his optimism. He grew up striking out the town team and joked in later years that he had been born with a ball in his hand. By the time he was a teenager, he knew his lightning left arm might take him far away from home.

A young black ballplayer’s best bet back then was to catch on with a barnstorming team. Donaldson joined the Tennessee Rats in 1911 and ventured deep into the Midwest, pitching against town teams in the rural Dakotas, Iowa, Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin. The Rats played as many games as they could book, lived in the bus, ate out of paper bags, and considered themselves lucky.

Derogatory experiences were a way of life. Even the team name was meant to convey filth to white fans. Various newspapers called them “darkies.” The Rats survived off gate percentages and passed the hat when somebody hit a home run -- sometimes courtesy of Donaldson, who played centerfield when he wasn’t pitching.

Donaldson understood that discrimination was part of the deal, and years later, he recalled how fans paid admission for the right to say what they wanted, but he refused to be anything less than dignified. “When I go out there to play baseball,” Donaldson said, “It is not unusual to hear some fan cry out, ‘Hit the dirty n-----.’ That hurts. For I have no recourse. I am getting paid, I suppose, to take that. But why should fans become personal? If I act the part of a gentleman, am I not entitled to a little respect?”

Donaldson’s dignity moved Gorton, who traveled to Glasgow and interviewed anybody in the town of 1,263 who said they had a memory of the hurler. Gorton read every edition of the local newspaper from 1905 until 1930. He found no descendents, but did find a rich oral history.

“He got along with everyone,” Gorton says. “People who I talked to said they didn’t see him as a black person, they saw him as a great baseball player and they wanted him to play on their team. That was remarkable to me.”

So were Donaldson’s exploits. Gorton collected what he could and then began a one-man letter-writing campaign to public libraries and historical societies throughout the Midwest, providing strangers with leads if Donaldson had been to their town, and asking for their help. One headline at a time, Donaldson’s games arrived in Gorton’s mailbox, and the lefty came back to life.

“Donaldson, the left handed colored man, registered the phenomenal record of nineteen strikeouts.”

“Struck out, by Donaldson, 16.”

“One of the greatest pitchers in the bush today.”

“Donaldson, the southpaw, did the twirling act and he had the best of them guessing.”

“Donaldson was again on the mound and those who witnessed the game say he was as strong at the end of the twelfth inning as he was at the beginning of the game the day before.”

Soon, the forgotten pitcher had a volunteer army. Gorton’s network unearthed an 18-inning, 31-strikeout game, a 27-strikeout game and four 19-strikeout outings. But a bigger world awaited Gorton when his group began unearthing Donaldson’s career with the All-Nations team, which was the forerunner to what became Negro League baseball’s most prestigious club.

"I WOULD GIVE $50,000 FOR HIM AND THINK I WAS GETTING A BARGAIN.”

The All-Nations were an inter-racial barnstorming team formed in 1912 that sold tickets on the gimmick that black, white, Latino, and even female ballplayers could play together. Donaldson teamed with a Cuban right-hander, Jose Mendez, to form one of the period’s most dominating duos. Donaldson continued to rack up strikeouts, and nearly a century later, Gorton continued piecing his career together:

“Struck out, by Donaldson, 28”

“Donaldson is credited with twenty-five strikeouts.”

“Struck out - by Donaldson, 22”

Over the past decade, Gorton’s network has uncovered about 1,900 games in which Donaldson pitched, many for the All-Nations, where Donaldson won his greatest fame and left ghosts to chase.

“He went from being this small town guy to this historically significant guy,” Gorton says. “I’d start tracking the All-Nations and found hundreds upon hundreds of games from all over. He was an automatic 10-strikeout-a-game guy.”

Gorton soon received a tip that helped put Donaldson’s physical ability in proper perspective. He heard from a man in St. Paul whose grandfather had taken motion picture film footage of Donaldson pitching. Gorton raced to the scene. The man “plopped me on the couch, told me not to say a word, and to just watch,” he says.

Gorton was stunned when he saw the greatest pitcher nobody ever heard of flicker to life, firing a few fastballs in 1925. When Gorton showed the video to a couple of veteran scouts, one said that Donaldson reminded him of a left-handed Bob Gibson.

“It’s amazing that nitrate film survived for 80 years in some moldy basement,” Gorton says. “I love watching it.” Then he offers hopefully, “There might be more! He has reels and reels.”

Still other evidence eludes Gorton, including a game against the New York Giants sometime around 1915 when Giants manager John McGraw is believed to have offered the light-skinned pitcher a contract if he would agree to pass as Cuban instead of black at a time when there were a handful of Cuban major leaguers.

Gorton can’t find the game, but he did find Donaldson’s version of the story, published in 1932. “One prominent baseball man in fact offered me a nice sum if I would go to Cuba, change my name and let him take me into this country as a Cuban,” Donaldson said. “It would mean renouncing my family. One of the agreements was that I was never again to visit my mother or have anything to do with colored people. I refused. I am not ashamed of my color.”

Donaldson’s dignity moves Gorton as much as Donaldson’s stuff moved McGraw, who is quoted as saying, “If Donaldson were a white man or if the unwritten law of baseball didn’t bar Negroes from the major leagues, I would give $50,000 for him and think I was getting a bargain.”

Gorton admires Donaldson’s vibrant elegance as much as All-Nations owner J. L. Wilkinson did. When he decided he wanted to rename the All-Nations, Donaldson suggested a title that would befit the grace and class he strove to inspire.

“Donaldson suggested the name ‘Monarchs’ one day when we were feeling around for a name,” Wilkinson told the Kansas City Call in 1948. “Right away, the name sounded good and we adopted it.”

Thus were born the legendary Kansas City Monarchs.

Satchel Paige became the most famous Monarch, but Wilkinson always believed that Paige would have to wait for his turn if he was in the same rotation with his former ace. “John Donaldson was the most amazing pitcher I ever saw,” Wilkinson said.

"HOPEFULLY THIS WILL END WITH DONALDSON IN THE HALL OF FAME"

After years of research, Gorton’s path finally led him to section 7, lot 1, row 17, grave 97. It was the first time he visited Donaldson’s unmarked gravesite at Burr Oak Cemetery. Gorton arrived with the conviction that began driving him a decade ago.

“From a modern perspective I still can’t understand how it could have ended up the way it did,” Gorton says. “It’s not right. Thousands of newspaper articles say how famous this guy was. How could somebody who was as prominent and at the front of an incredible period of change in this country end up in that situation?”

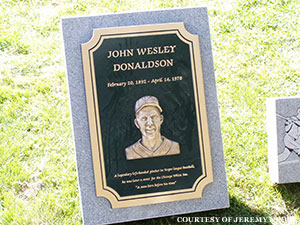

Donaldson finally gained a small measure of respect in 2004. Researcher Dr. Jeremy Krock, who leads the Negro League Baseball Grave Marker Project, learned that Donaldson was buried at Burr Oak. Krock credits Gorton’s work for bringing Donaldson’s career to light. A donation was made to purchase a head stone. The greatest pitcher nobody has ever heard of finally had a name again.

“Pete Gorton has single-handedly kept the John Donaldson name alive,” Krock says. “Pete championed the case for [Donaldson’s inclusion on] the Hall of Fame ballot in 2006 and started the Donaldson network going with a large number of dedicated volunteers. Hopefully this will end with Donaldson in the Hall of Fame.”

Gorton doesn’t consider the work done. Donaldson wasn’t elected in 2006, but Gorton firmly believes Donaldson belongs enshrined with half-brothers Rube and Willie Foster, both Hall of Fame Negro League left-handed pitchers. He wants Donaldson to be included more often in discussions of the best pitchers in Negro League -- and baseball -- history.

“We may never finish digging,” he says.

Gorton’s network discovered that Donaldson was the first fulltime black scout in baseball history when the White Sox hired him in 1949. When the White Sox learned that Donaldson had been one of their own, they paid $2,000 for the headstone.

Donaldson signed Negro Leaguer veterans Sam Hairston, Bob Boyd and Connie Johnson for the White Sox, but he couldn’t get the front office to commit to signing Birmingham Black Barons outfielder Willie Mays in 1950. Donaldson also knew about Henry Aaron and Ernie Banks when they were rookie Negro Leaguers, but couldn’t get the White Sox to let him sign younger black players. Frustrated, he resigned, and worked for the Post Office until his death in Chicago in 1970.

While researching in Memphis, a member of Gorton’s network saw a handwritten letter Donaldson wrote about Mays. Donaldson never lost his dignity even when he lost the player who would have made him famous all over again.

In the letter, he thanked the Black Barons owner for the opportunity to scout Mays. The closing of the letter speaks to Donaldson’s pride, in words he could have spoken just as easily to the visitor at grave 97, Peter Gorton, the man who trumpeted his forgotten name:

I am respectfully your friend,

John W. Donaldson

Journalist, author and scout John Klima is a regular contributor to ThePostGame.com and the author of Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, The Last Negro League World Series and the Making of a Baseball Legend. To learn more about pitcher John Donaldson or to contact the Donaldson Research Network, visit http://johndonaldson.bravehost.com.