Since the Giants moved to their sparkling new ballpark on the shores of McCovey Cove in 2000, it has hosted three World Series ring ceremonies, an All-Star Game, a perfect game and the power surge of Barry Bonds. Fifteen years later, it is still astonishing to consider how the Giants were able to get Pacific Bell/SBC/AT&T Park built in the first place. In Giant Splash, author Andrew Baggarly details how that happened along with more than a dozen other memorable moments that are part of this golden age of baseball in the Bay Area.

In the late 1970s, the San Francisco Giants were as close to irrelevant as any major sports franchise could be.

They struggled to draw 3,000 fans on weeknight games. The fan experience at Candlestick Park, with a frigid wind whipping through the shivering stands, was miserable. By the 1980s, they’d given up trying to market the unmarketable and instead tried to get fans to embrace the awful, hot dog wrapper–blowing experience by handing out a badge of honor -- the Croix de Candlestick -- and encouraging them to boo an anti-mascot called Crazy Crab.

For most of those years, the story wasn't whether the Giants could contend but where they would unload the moving vans once they left town for good. One year, it was Hackensack, New Jersey. Another year, it was Toronto, with the deal advancing as far as negotiating a payout for breaking the Giants' lease.

Horace Stoneham, the owner who brought the Giants from New York's Polo Grounds in 1958, eventually passed the problem and the team along to Bob Lurie. After several failed ballot initiatives, including two that would've resulted in a move to San Jose, Lurie threw up his hands, too. In 1992, he announced that he had reached an agreement to sell the team to a group of investors from St. Petersburg, Florida, for $115 million.

The Giants were leaving San Francisco. After the final home game in 1992, players scooped infield dirt and pried off pieces of the ballpark, taking whatever tangible memento they could. They were sure they would never set foot in Candlestick again, and as miserable as it could be, a boy always longs for home.

But Dodgers owner Peter O'Malley, sensing the importance of keeping his storied rival on the West Coast, urged Major League Baseball commissioner Fay Vincent to hold out for a local buyer. National League president Bill White, a former Giant who collected the first hit in Candlestick Park history, had a strong preference to see the team stay as well. So despite an agreement in principle with Tampa Bay and threats of a lawsuit, the league allowed a hastily arranged group led by Safeway CEO Peter Magowan to make a last-ditch effort to buy the Giants from Lurie.

Magowan grew up a Giants fan in New York, listened to Bobby Thomson's "Shot Heard 'Round the World" on a transistor radio, and made frequent trips to see his favorite player, Willie Mays, glide across center field at the Polo Grounds. Magowan's family -- he is the grandson of Charles Merrill, founder of the Merrill Lynch investment bank that popularized mutual funds to the masses -- happened to move to San Francisco around the same time that the Giants went west. But Magowan understood what it meant to uproot a team from its community. He understood the pain that would linger in San Francisco for decades. The day Lurie informed him of the sale to St. Pete, his heart sank.

The next day, he resolved to do something about it.

"I started to scribble down on a piece of paper what would be involved in trying to keep them here," Magowan said. "I said to myself, 'I don't know what can happen, but I'lll never forgive myself for not trying.'"

Magowan made a list of San Francisco power players and started dialing phone numbers. Financier Charles Schwab. Real estate magnate Walter Shorenstein. Gap Inc. CEO Donald Fisher. Charles Johnson, the principal at Franklin Templeton, and Johnson's general counsel, Harmon Burns. The Giants' local TV rightsholder at the time, KTVU. He borrowed and scraped and received pledges to the sum of $95 million, and when it became clear that offer wouldn't be enough, he went to the bank and borrowed $5 million more.

Magowan was trying to purchase a team that finished 26 games out of first place the previous season. His group had no plan for a new stadium. They had some idea how they could boost revenue, though. They could upgrade the concessions. They could schedule more day games, when the weather would be better. And they could capture the attention of the marketplace by signing the game's best player -- Barry Bonds, a Bay Area native and Mays' godson.

The shocker wasn't that Magowan's group received tentative approval to purchase the team. The real surprise came just two weeks later, when they arrived at baseball's winter meetings in Louisville and announced they had signed Bonds to a record-setting six-year, $43.75 million contract.

Lurie was livid. League owners already had blocked his deal with St. Petersburg, and he'd be receiving a lower price for the Giants as a result (although he did retain a $10 million interest in Magowan's group). Now, if the sale fell through for any reason, Lurie would be saddled with the game's most expensive player.

"You have to have control of the team to sign a ballplayer," Lurie told the Baltimore Sun at the time, "and they don't have a team. We do not want Barry Bonds to be a San Francisco Giant at that price."

The Giants already had announced the deal, though, leading to one of the most confusing press conferences in baseball history. Bonds walked into the hotel ballroom with his agent, Dennis Gilbert, and an entourage that included the player's father, Bobby, and the great Willie Mays. They sat on the dais and Bonds prepared to smile as he held up a jersey that represented a family heirloom as well as his new employer. Suddenly, a Major League Baseball official, out of breath, raced into the ballroom and relayed a message to Gilbert. The whole entourage quickly walked out through a kitchen door. If Twitter had existed at the time, it probably would've imploded.

It took 48 hours and some legal maneuverings before a contract could be drawn up that was amenable to all parties and included language that would shield Lurie in case the sale fell through. In the meantime, with Lurie still refusing to be the one to sign, Magowan not yet in charge, and GM Al Rosen having already stepped down, there was nobody left to put pen to paper on the Bonds contract. So Tony Siegle, the club’s vice president of administration, shrugged and did it; his signature was as good as anyone’s, he figured. In his many decades working for more than a dozen GMs, Siegle is most proud of becoming the answer to an impossible trivia question. He's the guy who signed Bonds' first contract with the Giants.

An odd chapter ended, but baseball in San Francisco did not. Not only did the Giants return to Candlestick Park in 1993, but Bonds, foreshadowing the dramatics to come, hit a home run in his first at-bat in the home opener. At the end of the season, he won the NL MVP award. The Giants had something far better to market than an anti-mascot.

Magowan and chief operating officer Larry Baer still had to solve the Candlestick problem -- and unlike Lurie, they would not pin their hopes on public money.

Although the Bonds signing had the immediate impact in the marketplace that Magowan and Baer predicted, with a record-setting 2.6 million fans passing through the turnstiles in 1993, all of their positive momentum evaporated the following year when baseball’s labor strife led to the cancellation of the season in August, along with the World Series.

(The stoppage came as star third baseman Matt Williams was on pace to hit 60 home runs, threatening Roger Maris' single-season record.)

Attendance plummeted at Candlestick in '95, along with almost every other major league ballpark, and didn’t begin to rebound for five years.

As a result, the Giants posted millions in operating losses. The inevitable cash calls were too much for some members of the ownership group to bear. They were fine to pitch in and do their civic duty to help keep the team from going to St. Pete. But they didn’t sign up for annual soakings. Magowan had a falling out with Shorenstein. Schwab sold his holdings as well. It was a constant dance for Magowan and Baer to keep the ownership group afloat, operate a team, try to win some actual games -- and push forward on a new ballpark, too. Burns, whose personal fortune kept rising as Franklin Templeton’s stock soared, often came to the rescue. As other owners bailed out, Burns took up a larger and larger share and would eventually and quietly become the team’s chief stakeholder.

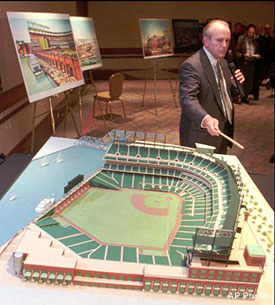

In retrospect, it’s stunning that Baer and Magowan were able to win support with San Francisco city officials in the aftermath of the most damaging event to hit the game since the 1919 Black Sox scandal. Yet in 1995, the Giants and the city agreed to a proposal to build a 42,000-seat, baseball-only stadium in the rather bleak South of Market area of San Francisco. It would be financed privately through the sale of more than 12,000 charter seats, including luxury boxes, plus corporate naming rights, ballpark signage, and a $170 million loan from Chase Manhattan.

Broadcaster Hank Greenwald suggested to Magowan that the new ballpark could be called the Polo Grounds West, and perhaps present a sponsorship opportunity for fashion designer Ralph Lauren’s signature brand. Magowan made a phone call. Lauren thought it was a wonderful idea, and asked if $1 million would suffice. Magowan sheepishly had to tell him: they were looking for 50 times that amount. And they got it, too, from the local Baby Bell.

In March of 1996, San Francisco voters approved a ballot measure and funding proposal by a two-thirds majority. Pacific Bell Park would be squeezed up against the bay into a 13-acre parcel in the area known as China Basin, so named because it was where the China Clippers of the Pacific Mail Steamship line docked in the mid-1800s. China Basin became home to lumber schooners after that, offloading the raw materials that built a growing city. Now the city wanted to redevelop the area, and a new ballpark would put the spurs to it.

Baseball’s stadium boom had begun a decade earlier, but the Giants were going against the grain. They relied on public money only as far as securing investments in local transportation and infrastructure. Pacific Bell Park would be the first privately financed Major League Baseball facility to be built since Dodger Stadium almost four decades earlier. The Giants were reestablishing a dangerous precedent for baseball owners, who had grown accustomed to receiving what they wanted for free and threatening to leave town until they got it. Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who berated Magowan in a Louisville hotel suite for the Bonds contract back in 1992, criticized the Giants again for taking on debt service and financing $357 million on their own.

But in so many ways, the Giants were ahead of their time. They saw the best of the new stadiums -- Baltimore's Oriole Park at Camden Yards among them -- and they knew what they did and didn't want. Instead of the double layer of luxury suites that belted many new parks, thus turning the upper deck into true nosebleed territory, Magowan directed for just 65 suites to be built on a single level.

"I think that is what happened in Chicago with Jerry's ballpark," said Magowan, shortly after the groundbreaking at Third and King. "He was really only catering to that corporate office luxury-suite type. He's got 150 suites in there. That’s his thing. What he does is to shove everybody in the upper deck another 25 feet higher, because he’s got to have two levels of his luxury suites to get up to 150. If you sit in the upper deck in Comiskey, bring your binoculars, because it’s the only way you're going to be able to see the ballgame."

Although the corporate customers always come first, Magowan was interested in a positive fan experience at all price points, and accessibility would be a priority in more ways than one. The Giants didn't have endless space for swaths of parking lots, but they didn't need them. A ferry service would bring fans from Marin County or the East Bay, dropping them off at a promenade just beyond the center-field fence. You could take Caltrain or light rail within blocks of the ballpark. Giants games would become true community events.

Magowan did not have to beg and borrow to sell those 12,000 charter seats. The demand was overwhelming. When the Giants began selling the charter rights in 1996, it didn’t take long before they could count more season-ticket holders for 2000 -- when the new ballpark would open -- than they could for 1997.

The Giants had no desire to build a glossier, more expensive version of Candlestick Park. So they consulted with Bruce White, an aeronautical engineering professor at UC Davis, who built a scale model of downtown San Francisco and tested wind patterns to determine just how blustery it would be at China Basin. White had to deliver bad news: the prevailing design, with the skyline view beyond the center-field fence, would have resulted in a ballpark just as windy as Candlestick. But a 90-degree rotation, with a line from home plate to straightaway center field pointing roughly due east, would shield most seats from the wind. The plans were redrawn. Problem solved.

Magowan traveled to Coors Field and toured the Colorado Rockies' new ballpark with Joe Spear, the principal architect for HOK Sport. They talked about sight lines and retro aesthetics. But mostly, Magowan was fixated on how his new park would play. He wanted something unique. He wasn’t interested in a cookie-cutter outfield, and besides, the small parcel demanded asymmetry. When the city of San Francisco further insisted on a public walkway between the right-field fence and the bay, shrinking the distance to just 309 feet from home plate to the right-field pole, Spear came up with the idea for a 25-foot brick wall -- the arcade -- with archways built in so passersby could steal a free look at the action. Some owners would have howled at the idea of giving away their product, even from so far away. But Magowan loved the romantic notion of a modern-day knothole gang. And, of course, there would be the ballpark’s official address: 24 Willie Mays Plaza, with 24 palm trees encircling a statue of Magowan's boyhood idol, freezing the Say Hey Kid as he dashed out of the batter's box.

Magowan borrowed from Wrigley Field, too. He liked the way the bullpens were in foul territory, and not hidden behind an outfield fence, so fans could take note of when and which relievers were getting loose. He liked Wrigley’s traditional green seats, too, and the way every one of them faced the pitcher’s mound. And although the Giants would have the shortest right field in the league, in a nod to the Polo Grounds, the arcade would be designed to bank steeply toward right-center and create a 421-foot crown that would become either a triple’s alley or a place where home runs would go to die.

The ballpark's signature feature, however, other than the giant glove and Coke bottle above the left-field bleachers, was the possibility for home runs to splash into a narrow channel of the bay that would become one of the most famous places to paddle a kayak in America. It came to be known as McCovey Cove, as first suggested by San Jose Mercury News columnist Mark Purdy and the Oakland Tribune's Leonard Koppett.

As the Giants prepared to open the 2000 season in their splashy and splendid new ballpark, the players still had no idea what to expect. When they took batting practice in the unfinished stadium, the balls rocketed into the stands. Shortstop Rich Aurilia remembered delighting for his own statistics and feeling a twinge of guilt for his pitchers. The prevailing expectation was that Pacific Bell Park would be a bandbox. The very first game appeared to confirm it.

Kevin Elster sat out the 1999 season. His aspiration was to build andrun a bar in Las Vegas, not to restart his baseball career. He dealt with too many injuries and was fed up with too many politics after jumping from the Mets to the Yankees to the Phillies to the Rangers to the Pirates and back to the Rangers over a seven-year span. On Memorial Day weekend in 1995, when the Yankees were playing the Mariners, a Seattle hotel bellhop, not realizing he had the wrong room, knocked on Elster’s door.

"Mr. Jeter, your luggage is here."

That's how Elster knew the Yankees had called up their prized prospect and he'd be getting his release papers soon enough.

Elster had an odd career track. A glove-first shortstop when he came up with the Mets in the late 1980s, Elster bolted out of nowhere to hit 24 home runs in 1996 with the Texas Rangers. Then he hit 15 over the next two years combined. Seemingly out of baseball after 1999, he was cajoled into signing with the Dodgers on a minor league contract by Davey Johnson, his onetime manager with the Mets. When Elster made the Dodgers out of spring training, he moved back into his parents' house in Orange County.

At the start of the 2000 season, as the Dodgers began a three-city road trip in Montreal and at New York’s Shea Stadium, Elster started four of six games and went 4-for-14 without a home run. When the Dodgers arrived to open up Pacific Bell Park on April 11, Elster was in the lineup at shortstop, batting eighth in front of pitcher Chan Ho Park.

The Giants had opened the season on the road as well. Manager Dusty Baker's team went 86–76 the previous season, good enough for a second-place finish but nowhere near qualifying for the playoffs. They began the 2000 campaign at Florida and Atlanta, losing to future Hall of Famers Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine to finish a 3-4 trip. But they had a day to rest up for the celebratory debut of baseball at Pacific Bell Park, when they would send Kirk Rueter to the mound.

Rueter already had started the first unofficial game at the ballpark 12 days earlier, when the Giants beat the Milwaukee Brewers in an 8–3 exhibition victory. The ballpark played even livelier in a second dress rehearsal against the New York Yankees, when Bonds hit the first home run with a first-inning shot off Andy Pettitte. Third baseman Russ Davis also homered twice, but Jorge Posada, Paul O’Neill, and Roberto Kelly went deep for the Yankees in their 11–6 victory.

Then the day finally arrived: the home opener at Pacific Bell Park.

A sellout crowd of 40,930 started chanting "Beat LA" during theopening ceremonies, which included a giant American flag in the outfield and thousands of red, white, and blue balloons. Magowan and Baer rewarded themselves with ceremonial first pitches, which some critics took to be self-aggrandizing. But it was their prerogative, of course. This place was their vision come to life.

When all the revelry had concluded and all the balloons had been released, plate umpire and Bay Area native Ed Montague signaled his readiness to Rueter. To a standing ovation, the first pitch was ... a ball. So was the next one. Then Devon White lashed a 2-2 pitch to center field for a single.

Magowan, and a packed house of Giants fans, sat down to consider the business of watching a baseball game in shirtsleeves.

The game was a back-and-forth affair. Bill Mueller singled in the first inning and Bonds scored him with a double down the right-field line. Catcher Doug Mirabelli, as fast as you might expect on the bases, became the first player to find the deepest recesses of right-center while legging out a surprising triple, the first of his career, in the second inning. (To this day, longtime club employees and members of the media still jokingly refer to that distant part of the ballpark as Mirabelli Cove.)

Elster stepped to the plate with one out in the third, and worked the count full before Rueter threw a fastball on the outer edge. Elster extended his arms and drove it past the 404-foot marker in left-center, where a fan in the first row caught it. The Giants would just have to live with it: a Dodger hit the first official home run in Pacific Bell Park history.

Bonds had to settle for being the first Giant to homer in their new home, which he did while taking Park deep to center field for a tiebreaking shot in the bottom of the third. But Elster came up again in the fifth after Todd Hundley had reached on a leadoff single. Rueter threw a fastball to almost the same location on a 2-1 count -- belt high and over the plate -- and Elster boomed it a dozen rows up in the left-field bleachers. This time, there was nothing ceremonial about it. It was just another Dodger hitting a home run to put his team ahead against their archrivals. And the fan who retrieved the ball treated it with all the proper scorn. He threw it back onto the field.

The Dodgers led 3–2 and they would not trail again. Shawn Green hit an RBI single off Rueter, who lasted six innings. The Giants got a run back on a wild pitch, but Geronimo Berroa singled off lefty Alan Embree to make it 5–3 in the seventh. Mirabelli homered in the seventh before Elster, who had drawn a two-out walk in the sixth, came to bat again in the eighth. Felix Rodriguez couldn't get Elster to chase a pair of two-strike pitches. Then the right-hander threw a fastball that tailed onto the barrel.

"High fly ball into deep left field, Kevin has hit another one," came Vin Scully's call. "Three home runs for Kevin Elster! Can you believe that story? A guy who had dropped out of baseball, stayed in shape merely to stay in shape, no thought about playing more baseball, and now he has a three-home run game."

Scully described Rodriguez’s fastball as “in a B.P. spot, and he just killed it."

"No one ever comes to the ballpark thinking they’re going to hit three home runs, least of all me," Elster said. "But it sure feels good to do this on a day like today."

Although J.T. Snow homered in the ninth off Dodgers closer Jeff Shaw, Mirabelli flied out to deep left field and pinch hitter Armando Rios grounded out to seal the Giants’ 6–5 loss.

Three Of A Kind Beats Full House, read the headline in the Los Angeles Times the next day.

Snow would go on to hit a much more important home run in the ninth off a closer later that season. For that day, though, the loss could only do so much to dampen a sellout crowd’s enthusiasm. They would be able to watch their Giants with a backdrop of the Bay Bridge, moonlight on the water, and no need for players to wrap up a season by scooping infield dirt as a souvenir. The moving vans did come, but they only traveled a handful of miles up Route 101 -- and landed in the best possible place. The Giants welcomed a new era of baseball.

They had no idea just how eventful, how celebratory, the next 15 years would be.

"People said, ‘You’ll never be able to keep the team here. You’ll never be able to buy it,'" said Magowan, shortly after the groundbreaking. “And once we had, ‘You’ll never be able to win the election, in San Francisco especially.’ We won with a two-thirds vote. Then, ‘You’ll never get it financed.' And this is all privately done. It’s never been done before. ‘You guys will not be able to do that.’ We got it privately financed. Now they say, 'Nobody will come to the stadium.'

"They're 0-for-3 on their predictions so far, so we’ll just have to wait and see what happens with the fourth prediction. But I think people are going to come."

-- Excerpted by permission from Giant Splash by Andrew Baggarly. Copyright (c) 2015. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Andrew Baggarly on Twitter @extrabaggs.