What is it like to chase after a ghost, uncertain where the journey will lead?

What steps does one follow to string together the life of a baseball Hall of Famer who was born in Virginia, died at a bus stop in Buffalo, and who was buried in an unmarked grave outside of Chicago?

What does having some closure mean to a family that, until only a handful of years ago, wasn’t even aware of the legacy left by an ancestor who impacted a game by pre-dating the game's biggest names?

Ask anyone who has chased after the memory of Pete Hill and the answers start to come together.

This is a story told in reverse. See, to understand where Pete Hill came from, one must first understand where he ended up. It's a search that begins in a cemetery on Chicago’s South Side, where it was believed that Pete Hill -- inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006 and then re-inducted in 2010 -- had been laid to rest more than 50 years ago.

But the search continues when one walks through the resting place where Pete Hill was likely to be found among the gravesites of many of his fellow Negro Leaguers -- only to discover that it wasn’t ever there.

So what's it like to chase after a ghost, uncertain where the journey will lead?

Ask a 29-year-old budding documentary filmmaker, a middle-aged anesthesiologist and the great nephew of one of the greatest Negro baseball players ever, and the answers start to come together.

But as each of them discovered, putting the pieces of Pete Hill’s life doesn't come easy.

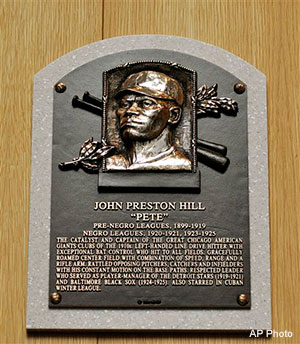

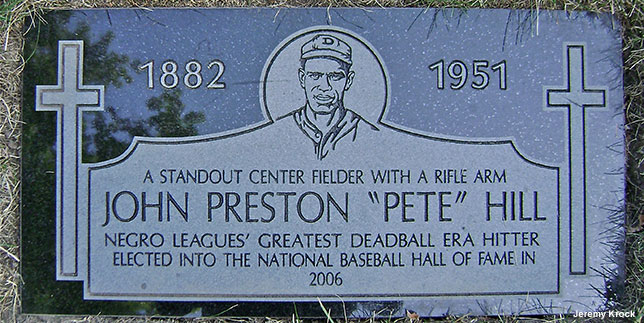

Pete Hill's baseball legacy can be summed up among the 75 words inscribed on his Hall of Fame plaque in Cooperstown. Listed among his career accomplishments, Hill is characterized as a left-handed line drive hitter with exceptional bat control who hit to all fields and who roamed centerfield with a combination of speed, range and a rifle arm.

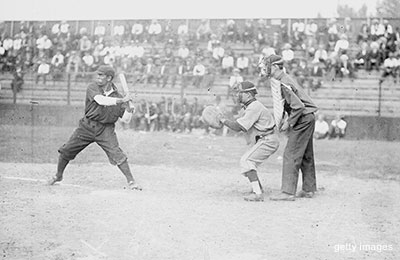

During his career with the Philadelphia Giants, Leland Giants, Chicago American Giants, Detroit Stars, Milwaukee Bears and Baltimore Black Sox, Hill became known as one of baseball’s most consistent hitters. While playing with Detroit in 1919, Hill clubbed 28 home runs – one shy of the number Babe Ruth had hit while playing in more games.

Hill’s power often drew him comparisons to Ruth while his acumen for hitting led to Negro baseball experts using Hill’s name in the same sentence with Ty Cobb.

But because he played in his prime before 1920 when Negro League stars Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige and Buck Leonard were just starting their careers, many of Hill's accomplishments went largely unnoticed.

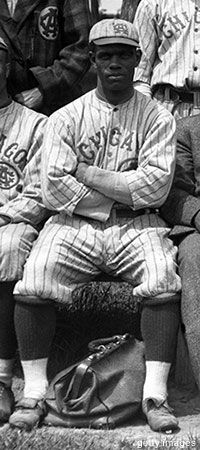

It’s a legacy that doesn’t set well with Ron Hill. The great nephew of Pete has spent the past six years piecing together his Hall of Fame ancestor's career in a collection of scrapbooks filled with anything he could get his hands on that tell Pete Hill's story.

"It was a very forgotten type of history ... we had no idea of how great this man was," Ron Hill says. "I mean, how many people in this country may have connection to a great person and don't know it?"

Ron Hill has always been more interested in football than baseball. But when a cousin contacted him in 2009, saying there may be a possibility that he was related to a Hall of Famer, it spurred his interest.

With the help of researchers and others, Hill began to understand just what Pete Hill meant to baseball -- even if others hadn't. He soon discovered that a man who had been the part of the first generation post-slavery was more than just another ballplayer.

"When you talk about people like Josh Gibson, he was a pioneer before them," Hill says. "He made them who they were. If you look at Negro baseball, they only start with Josh Gibson and that era.

"Before that era, those guys were the pioneers and so history’s really not telling the story."

Telling the story is where Keith Carmack enters the picture.

As a filmmaker, Keith Carmack is always looking for a great story.

So when he came across a story in the Chicago Sun-Times about the forgotten history of one of Chicago’s Negro League heroes, he was intrigued. As talented of a player as Hill appeared to be in his day, the fact no one really knew anything about what had happened to him once his playing career ended in 1925 was what stuck with Carmack.

At the time, Carmack was playing in a Chicago rock band, hoping to connect with a major recording label. But once he started to consider a project that could piece together the untold story of a man who entered Cooperstown years before, everything changed.

“I felt like Field of Dreams was happening to me,” Carmack says.

Carmack maxed out a handful of credit cards to purchase film equipment, intent on making Hill's story into a documentary. There were so many layers to peel back starting with the fact that at the time of Hill's Hall of Fame induction in 2006, none of his family had been present.

Along with others trying to piece together Hill's story, Carmack learned that incorrect information -- including Hill's first name and birthplace -- had been provided to the Hall of Fame when he joined 16 other Negro League inductees. His given name, John Preston Hill, has been incorrectly inscribed as Joseph Preston Hill, leaving Ron Hill and other relatives unaware that a man they knew as Uncle John had actually been one of the greatest hitters of his time, credited with more than 4,000 hits during his career.

Hill was re-inducted into the Hall of Fame four years later on what would have been his 126th birthday. Carmack, who is now in the finishing stages of completing his documentary, "Is This Heaven?" knew he was onto a great story.

"Everyone kind of knew that yeah, (Hill) was a really good ballplayer, but the full spectrum of what this guy accomplished was definitely not there," Carmack says. "When I started piecing it together, all of a sudden you realize that this guy was one of the greatest of all time possibly and we just don’t know."

Where to begin and where to go from that point, Carmack soon learned, would take him on a five-year journey.

Carmack started where he, like many others, believed Hill's story had ended -- in a cemetery on Chicago’s South Side.

Burr Oak Cemetery is a 150-acre expanse of land located just outside Chicago's city limits. Before 2009, when four cemetery workers were charged with digging up more than 200 grave sites and dumping the bodies into unmarked mass graves with the purpose of re-selling the plots, the cemetery had been home to some of Chicago’s most prominent African American residents.

Many believed that after his death in 1951 at the age of 69, Hill had been buried at Burr Oak alongside of other prominent athletes and musicians. But like much the rest of Hill's story, his final resting place was shrouded in mystery.

Carmack reached out to Dr. Jeremy Krock, an anesthesiologist who started a foundation to place headstones on unmarked graves of Negro League ballplayers like Hill.

As part of his grave marker project, Krock began studying the 2006 Hall of Fame class and discovered a handful of the 17 inductees did not have grave markers at their burial sites.

With Hill, all Krock had to go on was that after passing away at a Buffalo bus stop, Hill's body had been shipped to Chicago. During the course of a couple of years, Krock and others began to piece together where Hill may have been buried, leading him first to Burr Oak and then to nearby Alsip, Ill., where he found Hill's body to be buried in an unmarked grave in Lot 20, Block 10 of Section 35 inside Holy Sepulcher Cemetery.

As it turned out, Pete Hill’s son had married into a Roman Catholic family, which had purchased three plots at Holy Sepulcher. For one of the first times during the time he had placed grave markers on the graves of Negro League players, Krock felt as if he had helped solve a mystery.

"It was a sense of relief to finally find him," Krock says.

Getting there, however, hadn't been easy. Early on, Krock was grasping at straws, studying transit notices and sending emails to Chicago-area funeral homes that may have handled the arrangements after Hill’s death.

Of the 32 grave markers Krock had placed during the past 12 years, there was something about Hill’s story that made this mission different.

"I think it's the fact that he was lost,” Krock says. “(Hill) had such an impact on black baseball and here he has a plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but he didn’t have a plaque on his grave. No one knew where he was buried.

"That’s what was most compelling -- no one knew where he was. Not even his family."

In the years since Hill’s Hall of Fame re-induction, his story has started to pick up traction.

The mystery of whatever became of him drove much of the curiosity, giving Carmack plenty of work to complete. What was to have been a one-year project has turned into a five-year mission -- one that Carmack hopes reaches an apex at the Chicago International Film Festival, which will take place later this year in October.

While much of the production work has been completed on the film, Carmack has raised $2,000 from a Kickstarter project that Carmack hopes will help bring in the $6,800 that he needs to finish a film that currently sits at about an hour and 20 minutes.

Although the project has lasted longer than he originally anticipated, Carmack believes he may have one of the most complete stories of a baseball Hall of Famer that very people knew of before the mystery of what happened to Pete Hill began to take shape.

When a new revelation would present itself, Carmack would get off of his day job, rent a car and drive to a location to either interview a new character in the story or shoot footage for the film. He would often sleep in his rental car in a grocery store parking lot, shoot what he needed and then drive back to Chicago in time for work the following Monday, believing that every piece was another requirement to complete the puzzle.

"It just made sense to be there," Carmack says. "Every time I went out, there would be some connection saying, ‘Yeah, I should be doing this.'"

At times, Carmack wonders why he is the guy that has managed to put Hill's life together and into a finished product he hopes to share later this year. He looks at what is nearly a finished product and is amazed that somehow, everything came together, culminating with a small ceremony in Cooperstown where he, Krock and Hill's living family members all came together to see Pete Hill finally receive the proper ceremony he hadn’t received in 2006.

Like with putting together Hill’s life, getting the Hall of Fame to re-induct Hill had required years of work. Through the work of Ron Hill and others who wanted Pete Hill's legacy to be correct, Hall of Fame officials received the documentation they needed to make things right, giving Pete Hill his proper place among baseball greats once and for all.

It's a moment and a piece of Hill’s story that everyone who had been chasing his ghost for years had been waiting for.

For Hill’s great-nephew, the moment -- while gratifying -- provided evidence that African American players like Pete Hill continue to fight some of the injustices that Civil Rights workers and advocates have been trying to erase for years.

And now that Pete Hill's story can be told, the great nephew who never understood what Hill means to baseball will continue to work to make sure it’s a story that isn't forgotten.

"Pete Hill was in that dilemma that he never existed," Ron Hill says. “A lot of people now know who Pete Hill is. ... my thing is that I believe he was one of the greatest ballplayers that ever lived but who never really got the recognition for it.

"I don't feel bitter about it. I feel honored because it came out now and it makes me want to tell my neighbors that this man’s family came from slavery and he went to the Hall of Fame. Right now, we're not going through anything and that means that we have hope."

All thanks to a Hall of Famer that until only a few years ago, no one knew really existed.

-- For more information about the film, go to the "Is This Heaven?" Kickstarter page. Email Jeff Arnold at jeff.arnold@thepostgame.com and follow him on Twitter @JeffArnold_.