As one of the most successful general managers and team presidents in NFL history, few people understand how to create the blueprint for a winning football team like Bill Polian. After building the Buffalo Bills team that went to four consecutive Super Bowls and taking the expansion Carolina Panthers to the NFC championship game just two years after the team's creation, he was responsible for the Indianapolis Colts drafting Peyton Manning with the first overall pick in 1998 and oversaw the team's victory in Super Bowl XLI. Now, Polian shares his blueprint for building a successful football team in The Game Plan: The Art Of Building A Winning Football Team. In this excerpt, Polian analyzes his trade of Marshall Faulk to the Rams and opting for Edgerrin James rather than Ricky Williams in the draft.

The most significant move after our first season, and a highly controversial one, was when we traded Marshall Faulk. That was quite the controversy, and I’m not sure that the story behind it has ever been fully told. Marshall, who would go on to become a Hall of Famer, was phenomenal with the ball in his hands. He was perhaps the best route runner of any back I have ever seen.

Marshall was darn good at running the football because he had home-run speed and he could make people miss. The only thing that he couldn’t do as a runner was short-yardage and goal-line power running because he wasn’t that big. Also, the way that Tom Moore, our offensive coordinator, and Howard Mudd, our offensive line coach, had constructed the offensive system, there were times when the running back was a blocker, which wasn’t Marshall’s strong suit, either. But he was a Hall of Famer in every respect.

The problem we had with Marshall was his dissatisfaction with his contract, and I couldn’t blame him. It was excessively long and bound him in ways that his agent surely regretted after it was signed.

Marshall was a much, much better player than the deal had called for. But we couldn’t renegotiate it because the money he wanted, or anticipated getting under the cap, would have squeezed us terribly. To Marshall’s credit, he played his heart out for every single game through the ’98 season. He never indicated any lack of intensity or effort on the field.

Not surprisingly, his agent approached me soon after the seasonto let me know there was going to be a holdout. Knowing that it was coming and that it wasn’t going to be pleasant and that it would have been devastating for a young team to handle, we decided to see if we could trade Marshall, who was at the peak of his career. We were asking for a one and a two and I inferred that less than a one, with some other combination, would do it. Surprisingly, we didn’t have many takers.

We finally ended up trading Marshall to the St. Louis Rams for second- and fifth-round draft choices. The trade was announced the day before the 1999 draft, and other than Jim Irsay and Jim Mora, not many people in the organization knew it was coming. When word got out about the deal, it was earth-shattering news at our facility. The building was very small by the standards of NFL team headquarters today, so I could hear some people yelling, "What? No! They can't do that!"

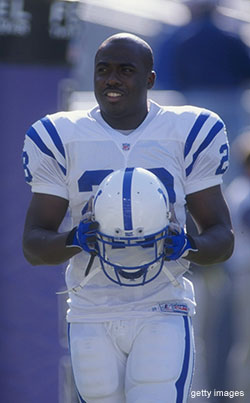

But that was only the first half of what would initially be seen as a very unpopular doubleheader. The next day, we used the fourth overall pick on the lesser known of the two top running backs in the draft: Edgerrin James of the University of Miami. Ricky Williams, the Heisman Trophy winner from Texas, was the household name that most people thought we would select. Instead, the New Orleans Saints chose him with the next pick, which they acquired by trading their entire draft (plus their first- and third-round picks in 2000) to the Redskins, because that was how badly they wanted Ricky Williams.

As we were just getting ready to wrap up for the day, Dom Anile, our personnel director, tossed his car keys to Tom Telesco, one of our scouts, who is now general manager of the Chargers.

"Here, Tommy, go start my car," Dom said. We all laughed at the implications of that statement.

Despite the public outcry, Dom and I had no hesitation about our pick whatsoever. The reason media analysts and fans knew a lot less about Edgerrin than they did about Ricky was because the NCAA had placed Miami on probation and, therefore, the Hurricanes' only nationally televised game the previous season was against UCLA. In our mind, there really was no comparison between the two.

For one thing, the way Ricky carried himself, the way that he lived his life, was entirely inconsistent with being a good football player. Second, we weren't convinced that he really cared about football. Third, when you broke it down, Ricky was good, but not great, and that was what he turned out to be as a pro -- good, but not great. I don't know whether or not his love of football held him back because he had great gifts, but he obviously didn't distinguish himself.

Edgerrin, on the other hand, had incredible gifts to go along with a clear love for the game and desire to excel. Although he was a scholarship player at Miami, Edgerrin had to earn his playing time. He told us that if it weren't for some bad luck for Frank Gore and Willis McGahee with injuries, he might not have ever gotten a chance to play. Edgerrin also described Frank as the most gifted running back he had ever seen, and Frank has subsequently demonstrated as much during his career with the 49ers.

Edgerrin’s interview with us was tremendous, while Ricky's was the complete opposite. We decided to meet with Ricky at our facility because we were told that he really didn’t like going out to restaurants. We catered a big dinner for him from St. Elmo’s, the famous Indianapolis steak house, in a conference room. Ricky walked in, sat down and was essentially non-communicative.

On top of that, Ricky had done very poorly in his pre-draft workout. He ran something like a 4.75-second 40-yard dash. He certainly didn't match up with Edgerrin in terms of the numbers and that told us that he wouldn't be a good fit in our offense. We used a zone-blocking scheme, which means the blockers are moving laterally and are essentially taking defenders where they want to go. The running back has to have patience, wait to see the hole open, and then tremendous vision and acceleration to get through the hole. He has to go from a geared-down state to a hundred miles an hour.

Ricky’s acceleration in the hole was average at best. He was much better suited to a power running system, where he would use all of that body mass that he had and the explosion he had to get to the hole and maybe run over people. Then, when he was out in the open, he could throw it into fourth gear.

Adding to the initial criticism we received for choosing Edgerrin over Ricky was the fact that before signing his contract, Edgerrin held out for a couple of weeks, which caused him to miss our rookie camp. We played him sparingly in the first preseason game, but he saw more extensive action in our second, at New Orleans.

I was seated in the Superdome press box with Dom and Chris. We were one booth away from the owner, so we could see Jim Irsay and Jim could see us. With the offense down in the red zone, we ran an outside stretch play to the right, and Edgerrin ripped off about a seven- or eight-yard gain. We ran the very same play again, and this time Edgerrin made two guys miss before running about 15 yards for a touchdown.

I looked over at Jim, he looked over at me and gave the thumbs up.

We wound up going 13–3 in our second season, a complete reversal of our first year and the biggest one-season turnaround in league history.

-- Excerpted by permission from The Game Plan: The Art Of Building A Winning Football Team by Bill Polian with Vic Carucci. Copyright (c) 2014 by Bill Polian and Vic Carucci. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Vic Carucci on Twitter @viccarucci.