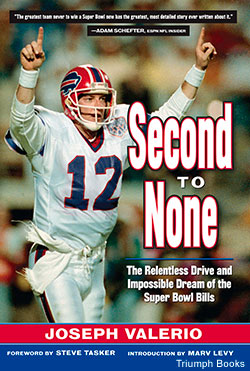

Fans in Buffalo should be thrilled to learn that the estate of late Bills owner Ralph Wilson has agreed to sell the franchise to Sabres owners Terry and Kim Pegula. That means the Bills will be staying in Western New York, a region whose identity is linked to the football team. In his new book Second To None author Joseph Valerio revisits how the Bills made an unprecedented four consecutive trips to the Super Bowl. But he also examines why this team means so much to its community, and it goes back to the formation of the franchise. Here is an excerpt:

When the American Football League announced in 1959 that Buffalo would to field one of its eight teams, it seemed to lift the spirit of upstate New York. Those truly were the good old days for this working-class American city. Big industries seem to stretch out in every direction: Bethlehem Steel, Republic Steel, Anaconda, General Motors, Ford, and Dunlop, companies that enriched the American dream and experience, thrived in and around Buffalo. With the advent of a professional football team, Buffalo had finally achieved major-league status. Everyone, it seemed, was enthusiastic and bursting with civic pride. It hardly mattered that the Bills would be playing in creaky old Buffalo War Memorial Stadium -- "the old rock pile," as it was dismissively known -- which was often used for stock car races.

"It was just a great time and it was a different time," Donn Bartz, one of the first season-ticket holders said. “We used to be able to bring in our lunches, cases of beer, and you'd sit there and eat and drink and enjoy the game."

Tailgate parties right on the 50-yard line. How much better can it get?

The city of Buffalo may have gained a professional football team, but it never lost its small-town aura. "We'd park right on the streets or in somebody’s front yard. Not like nowadays," Bartz said. Those really were the golden days before personal seat licenses, corporate suites, and preferred parking fees began to fleece fans.

By 1970, when the Bills and the rest of the AFL merged into the NFL, plans were already under way to build a new stadium in Buffalo, one befitting a team that had won two AFL championships. “The merger really gave pride to the city,” Bartz said. "We really felt the pride of saying 'we belong to the NFL.' It gave some credence to the city. We were a major-league town."

One developer even wanted to build an all-weather stadium -- a dome! -- in suburban Lancaster, but the local high school protested, and that proposal was eventually dropped. At that time the city was experiencing economic stress. Buffalo's aging steel industry and obsolete processes were no longer profitable, and Bethlehem Steel practically shuttered its entire operation. Other industries were departing for the Sun Belt. In the two decades from 1960 to 1980, nearly 40,000 factory jobs were lost. The fragmentation brought about by urban renewal exacted a terrible price: large pockets of neighborhoods were razed and citizens were moved into high-rise projects. The ethnic and diverse middle class was all but uprooted; communities -- built upon immigration and migration and supported by work in the steel and manufacturing industries with substantial union wages -- suffered.

Finally, after years of litigation, a new 80,000-seat stadium was erected on the outskirts of Buffalo, in Orchard Park, under the management of Frank Schoenle and his construction company. By the time the new venue opened for business in 1973, it had already been named Rich Stadium after a local corporation, Rich Products -- for a fee. Ralph Wilson had negotiated a 25-year, $1.5 million deal for the stadium’s naming rights, one of the earliest such marketing agreements in American sports. Wilson was even canny enough to work out a compromise with the company who wanted the stadium to be named Coffee Rich Stadium after its premier product. A quarter of a century later, when the agreement expired, the stadium was renamed Ralph Wilson Stadium -- but only after the Rich Corporation balked at paying a whopping new rights fee, which would have brought the price up to par with other naming rights at the time.

For all but a few months of the year, the Bills were the lifeblood of the town. From the time in midsummer when they reported to training camp until well after the last game of the season, in virtually every town in upstate New York fans devoured football tidbits and gossiped about their team. Long before sports talk radio, the Bills commanded 24/7 coverage throughout the region.

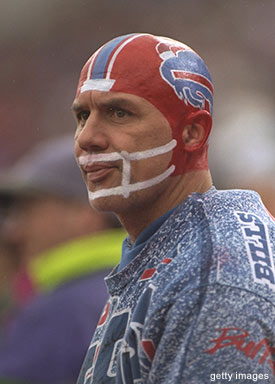

"When football came it gave a release to the people, so they had something besides work in their lives," Bartz said, "something else to occupy their time and make them feel good. It wasn’t just work, eat, and sleep. You have your coffee break at the water cooler and you're always talking about the team. A lot of people would talk until Wednesday or maybe even Thursday about how bad we were last Sunday. If it was a tough loss, you didn’t start looking ahead to the next game until Friday. Some people, it eats at them for quite a while. I have a few friends like that. But that’s the nature of the beast. We live and die football. We live and die Bills."

Bill Polian believes the bond between the team and the town is "unique, to use a euphemism." He said of that passion, "It only exists in Green Bay -- and Boston with baseball -- in professional sports. Yeah it’s regional, but it's 365 days of the year, 24 hours of the day. The thing that's unique about Buffalo is that in most other cities it will be the business leaders who tend to be transplants. That’s just the nature of business in America. Politicians and people who work in government, they may be casual fans they’re not real hard-core fans. But Buffalo's different.

"The congressman who represented the south towns where the stadium is located, and where the vast majority of us live, was Jack Kemp, a former Bills quarterback. The county executive was Ed Rutkowski, a former Bill. The mayor when I was there was Jimmy Griffin, a legendary guy who was loved for his down to earth, everyman qualities and was a brilliant politician and mayor as well."

Griffin is best remembered for his outspoken ways. During the blizzard of 1985, he suggested the people in Buffalo should "go home, buy a six-pack of beer, and watch a good football game." He was forever known as “Jimmy Six-Pack.”

These men, who ran the city, shared at least one thing in common with each and every one of their constituents: they cared passionately about their Bills. Several of them would gather at the Quarterback Club every Monday after a home game during the football season in a restaurant in Memorial Auditorium where the politicians would flank Polian on the dais. “You had up to 1,500 people there,” Polian said, “and lunch was being served and the mayor would say to me, ‘Hey Bill, what are we going to do about right corner? We got to get play out of right corner. We're getting picked on. What are we going to do about this?’” Polian laughs, as if he still has to answer for that a quarter of a century later. "But he was a dyed-in-the-wool fan. I mean he cared about the Bills as much as he cared about anything else. And that’s the way it was, 365 days of the year, 24 hours a day. Everything Bills, all the time. People really cared."

It was a birthright to be a Bills fan, as if your parents had signed some certificate at the hospital before they brought you home, a baptismal right. "Most importantly, every young child who comes into the world in western New York for the 10 years I was there was born a Bills fan," Polian said. "They were brought into a Bills family and he or she was a Bills fan from Day One."

Of course, the fans had not always reacted with such a religious fervor. When Polian arrived, attendance was at an all-time low, and there was talk of the Bills relocating to places such as Seattle or Jacksonville. Polian knew one of his foremost challenges was to build a strong and loyal fan base. If you build that, the players will come.

“We needed to try and create new ways to try and sell the team in the marketplace,” Polian said. "We felt we needed some corporate support, and some corporate leaders were great along those lines. And the biggest outfit to come out of that effort was Marine Midland Bank, and we hit the nail on the head. We made retail tickets available through the bank outlets. We created the Shout Zone, the signature for that campaign. We didn't discount tickets, but we kept pricing realistic for the marketplace. We played one preseason game at home instead of two, which effectively created a discount. We discounted season tickets as opposed to individual over-the-counter gameday sales. And that combination, coupled with extensive availability in the branches in western New York, made it really a good thing. We started to move tickets and started some esprit de corps, teamwork with bank employees, and got it going in the right direction."

As Polian began to construct a better team, attendance began to steadily increase. It wasn't as if the Bills were in the fight of their lives for the entertainment dollar in western New York. They were pretty much the only game in the region. Sure Buffalo had a philharmonic and a first-rate art museum, but football -- well, that was the big show. The Bills gave citizens a different sense of self-esteem. It gave them a national identity.

Dick Zolnowski, who was a police officer in Buffalo for 21 years, remembers the surge in pride he felt when the Bills advanced to the 1988 AFC Championship Game. "On every street corner they were selling Bills souvenirs and they had lines down the streets," he said. "You'd go to other cities, and when they heard I was from Buffalo, they were really excited, and all they wanted to hear was stories about Kelly and Thomas and Bennett. I was in Fort Lauderdale to see my brother, and it was around Christmastime. People wanted to know what were the players really like, what was going on in Buffalo. It made me feel really good. I was like the hit of the party. Buffalo, you would think it was New York City or London. You were from Buffalo. You were at the top."

-- Excerpted by permission from Second To None by Joseph Valerio. Copyright (c) 2014 by Joseph Valerio. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon and Barnes & Noble.