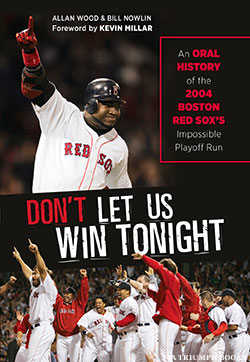

Commemorating the 10th anniversary of the team's unprecedented championship run, Don't Let Us Win Tonight: An Oral History of the 2004 Boston Red Sox's Impossible Playoff Run takes fans behind the scenes and inside the dugout, bullpen, and clubhouse to reveal to baseball fans how it happened, as it happened. The book highlights how, during a span of just 76 hours, the Red Sox won four do-or-die games against their archrivals, the New York Yankees, to qualify for the World Series and complete the greatest comeback in baseball history. Then the Red Sox steamrolled through the World Series, sweeping the St. Louis Cardinals in four games, capturing their first championship since 1918. This excerpt provides the context leading up to that season.

Any account of the 2004 Red Sox must begin on the night of October 16, 2003, when the New York Yankees capitalized on one of the most egregious managerial blunders in baseball history.

The Red Sox had come into Yankee Stadium needing two wins to capture their first American League pennant since 1986. They rallied in the late innings to win Game 6, setting the stage for a winner-take-all Game 7 with a matchup of Pedro Martinez versus Roger Clemens, a former Boston pitching star now toiling for the enemy.

Martinez had the upper hand that day, pitching seven innings and walking off the mound with his team ahead 4–2. Pedro's teammates congratulated him with hugs and high-fives, and pitching coach Dave Wallace told his ace he was done for the night. The Red Sox added an insurance run in the top of the eighth -- and fans prepared to watch the Boston bullpen, utterly dominant in the playoffs, nail down the final six outs.

Everyone watching was stunned when Pedro returned to the mound. Even as Martinez was mentally coming out of the game, manager Grady Little asked him for an additional inning. That decision cost Little his job. It's never been fully explained why Little went against the clear instructions of Boston's baseball operations people about Martinez’s use, or why he ignored the lights-out performances of his bullpen. Readily available statistics showed that once Martinez passed 100 pitches, he was much more vulnerable. Little had been reminded before the game not to push Pedro past that limit. Through seven innings, Martinez had thrown exactly 100 pitches.

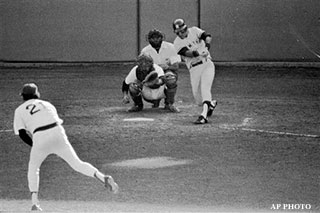

The Yankees promptly scored three runs off the fatigued Martinez to tie the game and won the pennant on Aaron Boone's 11th-inning home run. The Red Sox seemed to have had victory in their hands, but now their season was over.

It was a crushing blow to everyone affiliated with the team. Red Sox Chairman Tom Werner said he was "devastated" and "comatose" for a couple of months. Principal owner John Henry spoke for millions of Red Sox fans when he said he had no interest in watching the Yankees and Florida Marlins in the World Series.[1]

Boone's shot both ended the Red Sox's 2003 season and signaled the beginning of its 2004 campaign.

When John Henry and his group of investors (which included Tom Werner and Larry Lucchino) purchased the Red Sox in the spring of 2002, the team was under new ownership for the first time in nearly 70 years. Tom Yawkey had purchased the club back in 1933, and for nearly seven decades, either Tom, or his wife, Jean, or the Yawkey Family Trust had run the team. The Red Sox had gotten to Game 7 of the World Series four times -- 1946, 1967, 1975, and 1986 -- but had come up short each time.

Those years and many other near-misses, such as 1948, 1949, 1972, 1978, and 1999, were burned into the consciousness of diehard Red Sox fans, whether or not they were old enough to have actually experienced them. The number of times the team had fallen short seemed improbable and led many fans to see the Red Sox as perennial also-rans -- especially when compared to the Yankees.

The Henry-Werner-Lucchino trio may have been initially considered outsiders in New England, but each had a deep baseball background. They said all the right things about being humble stewards of the Red Sox franchise, showing a reverence for a team that was steeped in tradition.

After the 2002 season -- a summer of transition between the old regime and the new group -- the trio brought in a new general manager, Theo Epstein, who at age 28 was the youngest GM in the history of MLB. His baseball operations group used sabermetrics and their own progressive analysis to identify undervalued players in the market. To those ends, they hired baseball iconoclast Bill James as senior baseball operations advisor. Henry applied the same fact-based theories to baseball that he had used in his investment businesses.

The leadership group was new, but many of the pieces needed to contend in 2004 had been put in place by Dan Duquette, the previous general manager. Duquette had traded for Pedro Martinez in 1997 and signed him to a long-term contract. He had brought in free agents as disparate as Tim Wakefield and Manny Ramirez and had traded for Derek Lowe and Jason Varitek. Only weeks before he was cut loose, Duquette signed free-agent outfielder Johnny Damon. And under Duquette's supervision, the Red Sox farm system had produced fan-favorites Nomar Garciaparra and Trot Nixon.

Epstein added several other key pieces to those building blocks, bringing in such undervalued players as David Ortiz, Bill Mueller, and Mike Timlin and jostling Kevin Millar loose from an agreement with the Chunichi Dragons of Japan's Central League. Epstein correctly guessed that besides being productive players, they could withstand -- and actually thrive in -- the harsh glare of the Boston media and the sky-high expectations of the fan base.

Ortiz, Millar, and Mueller succeeded in Boston beyond all expectations. Once he received regular playing time, Ortiz became a slugging revelation, electrifying Fenway with his big bat and infectious smile and humor. Mueller hit .326, edging out teammate Manny Ramirez (.325) for the American League batting title. And Millar cemented his reputation as a fun-loving, locker-room cutup who rallied the team with the command to "Cowboy Up." The 2003 Red Sox scored 961 runs, 54 more runs than any other major league team. Boston also led all teams in hits, doubles, batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage. In fact, they posted the highest team slugging percentage of all time -- .491 -- topping the .488 mark set by the legendary 1927 Yankees.

Although there were no games on the schedule, Boston's rivalry with the Yankees raged on through the winter. During the 2003–04 off-season, Epstein made a flurry of moves resulting in three notable additions -- and there was one monumental trade that was not completed.

First, there was the matter of getting a new manager. On October 27, two days after the Florida Marlins defeated the New York Yankees in the 2003 World Series, Grady Little’s managerial contract was not renewed, and the Red Sox began looking for his replacement. After interviewing several candidates, including Angels bench coach Joe Maddon (who later settled in Tampa Bay), the Red Sox hired Terry “Tito” Francona, a former player who had managed a bad Phillies team for four seasons starting in 1997. In Boston, Francona was fairly unflappable, running the team with a steady hand yet still keeping things light in the clubhouse. He had a warm, easy rapport with his players and the media, a receptiveness to progressive ideas, and a desire to use the information he received.

Epstein had also been in touch with teams who were looking to shed some of their more expensive contracts. The Red Sox GM began talking to Arizona Diamondbacks GM Joe Garagiola Jr. about Curt Schilling. The burly right-handed pitcher -- the co-MVP of the 2001 World Series -- had told the Diamondbacks that he would waive his no-trade clause if he and his new team could agree to a contract extension. Schilling wanted to go somewhere familiar and comfortable, and to a contending team. He mentioned the Yankees and the Phillies (who he had pitched for from 1992–2000), but Schilling said he would not consider the Red Sox.

However, once he learned that Terry Francona was being considered for the manager's job in Boston, Schilling added the Red Sox to his list of possible destinations. A meeting was arranged. The Red Sox presented Schilling with an introductory letter. It stated, in part, “There is no other place in baseball where you can have as great an impact on a franchise, as great an impact on a region, as great an impact on baseball history, as you can in Boston.... The players who help deliver a title to Red Sox Nation will never be forgotten, their place in history forever secure.”[5]

The letter emphasized the team’s commitment "to create a lineup that would be relentless one through nine” and to create a pitching staff that was similarly relentless. “You are the key to the plan; in fact, you are the plan."[6]

There was the famous Thanksgiving dinner that Theo Epstein and Assistant GM Jed Hoyer had at the Schillings' home in Arizona, where the trade was eventually finalized. Schilling and the Red Sox agreed on a three-year contract with the provision that Schilling would receive a $2 million bonus if the Red Sox won the World Series during any of those three seasons.

Schilling quickly embraced his new team and its traditions, interacting with fans online and filming a couple of commercials -- one in which he practiced affecting a Boston accent and another in which he played a hitchhiker in the American Southwest. Asked where he was headed, he said, "Boston. Gotta break an 86-year-old curse."

A few weeks after trading for Schilling, the Red Sox landed one of the game's elite closers, former Oakland reliever Keith Foulke, signing him to a three-year deal in December. Foulke's 43 saves for the A’s led the American League in 2003; he also had a 2.08 ERA. Foulke already had a relationship with Francona since the new Boston manager had been Oakland’s bench coach in 2003.

Only two days after saying good-bye to Grady Little, the Red Sox placed left fielder Manny Ramirez, who had made periodic noises about wanting to be traded, on irrevocable waivers, meaning that any of the 29 other teams could have him as long as they assumed the remainder of his contract—five seasons and approximately $100 million. No team filed a claim. Although Ramirez was one of the best right-handed hitters in baseball, the new ownership group believed that the eight-year, $160 million contract Ramirez had signed with the old regime was too expensive.

The Red Sox had also been talking with the Texas Rangers about shortstop Alex Rodriguez, who had been voted the 2003 American League Most Valuable Player. In December 2000, Rodriguez, then only 25, had signed a historic 10-year, $252 million contract with the Rangers. Texas had finished in last place during each of the three subsequent seasons, and Rodriguez wanted out. He wanted to play for a contending team.

By mid-December, it was rumored that a trade involving the two disgruntled superstars was all but complete. Boston would send Ramirez to the Rangers in exchange for Rodriguez, then ship shortstop Nomar Garciaparra to the Chicago White Sox for outfielder Magglio Ordonez. It would be one of the biggest trades in the history of baseball. However, the deal fell apart because Boston wanted to restructure Rodriguez's contract. A-Rod was willing to accept millions of dollars less to come to Boston, but the Major League Players Association refused to give its consent, saying the Red Sox proposal would lessen the contract’s overall value.

About six weeks later, the Yankees stunned the baseball world by swooping in and completing a deal with the Rangers for Rodriguez, countering Boston's acquisition of Schilling with a mega-trade of their own.

Headlines in Yankeeland crowed that New York had bested the Red Sox yet again: “Summer Or Winter, The Yankees Show The Red Sox How To Win" (The New York Times) and, “This Rivalry Always Has The Same Ending” (Newark Star-Ledger). The back page of the New York Post boasted, “A-Rod Steal Is Bombers' Best Move Since Babe."

The Yankees also signed free agents Gary Sheffield (outfielder) and Javier Vazquez (pitcher). Sheffield was confident the Yankees would once again be playing in the World Series.

-- Excerpted by permission from Don't Let Us Win Tonight: An Oral History of the 2004 Boston Red Sox's Impossible Playoff Run by Allan Wood and Bill Nowlin. Copyright (c) 2014 by Allan Wood and Bill Nowlin. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.