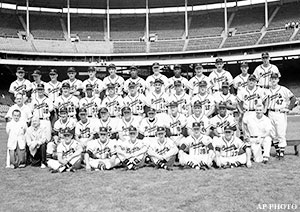

Meet the screwballs in charge – pitchers Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette of the Milwaukee Braves, a righty and a lefty joined at the hip, both who felt Casey Stengel tried to railroad their careers as young pitchers. Meet the sluggers -- Henry Aaron and Eddie Mathews, two teammates whose opposites were extreme, but whose differences brought them closer together instead of ripping them apart. And meet the beer swiggers -- Milwaukee, the town, the team and the time -- the first team to relocate in the 20th century, the first team to come to a new market, move into a new stadium and draw 2 million a year -- led by a visionary owner named Lou Perini, a construction man whose blueprints for baseball's future were liberally imitated by young Bud Selig, who grew up in Milwaukee during the High Life years of the Braves.

This is the story of baseball's greatest underdog -- the team that stopped the New York City baseball dynasty, when the Big Apple wore the World Series crown for eight long years. The rest of the country wanted a piece of the action, too, and Milwaukee's heartland tailgating, fan base and hometown support proved that small markets can win, too, if you build it right. In 1957, the Braves beat Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford and the rest of the Yankees in seven games, with Burdette and Aaron leading the way, upsetting Stengel's baseball machine, and making him regret the moment he came to Milwaukee and dared utter the phrase, "This place is bush league." Author John Klima tells this fascinating story in Bushville Wins! Here is an excerpt:

Milwaukee sportswriter Lou Chapman caught a cab from the Commodore Hotel in New York City to Yankee Stadium. It was a miserable, murky October day and the city was in a lousy mood. The Yanks were trailing the Series and now the news that had been anticipated for months was finally official -- the Brooklyn Dodgers were outta here, off to Los Angeles. The cabbie was beside himself. First it was the Giants now it was the Dodgers. This had all started when the Braves moved from Boston to Milwaukee. He couldn't imagine New York City as a one-team town. Who would the Yankees beat up on?

Tough break, Chapman said, but everyone knew it was coming. The ballplayers had all day to think about it. Tarp covered the field and a steady rain wiped out the workout before Game 6. Manager Fred Haney confidently predicted the Braves would win in six while Yogi Berra assured New York this thing was going seven. The big question for manager Casey Stengel was if Mickey Mantle could play. "I dunno," he said. "We sure need the kid but if he ain’t fit to play, nothing we can do."

One thing was for certain: the Yankees weren't so worried that it got in the way of a good time. Lou Chapman caught another cab back to the hotel later that night. While at a stoplight, he glanced at the cab next to him. There was Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford ----faced in the backseat and having a blast. It became one of Chapman's favorite war stories. "They exchanged greetings," Chapman's son Richard said. "But then again, those guys probably told him to ---- off." But they probably had a smile on their faces while telling Chapman off.

Mantle liked Chapman enough that he allowed him to visit his hotel room for an interview. Chapman wanted to know if Mantle could play. Mantle, laid up in bed, several sheets to the wind, was blurry, bloodshot, and hung over, but he was a helluva guy. Mantle respected how Chapman went the extra mile to get the story. They didn't call Chappie "Gumshoe" for nothing. Mantle mumbled a vow that he would be ready to play. Then his eyes glazed closed and he blacked out. Chappie, sport that he was, made sure that the photograph taken of him interviewing Mantle while he was completely hammered was never published. He saved the photo for the rest of his life. That was the way of the world then. Good writers and good ballplayers trusted each other.

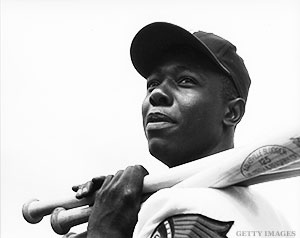

The following day, Milwaukee camped out in front of TVs and radios to follow Game 6. They were itching for a party and enjoyed their newfound nickname. "Downtown TV fans expect the value of hayseed to skyrocket on the nation's baseball market Thursday when our 'Bushville, USA' team goes to harvest," the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote. The first toast of the day came when Bushville learned Stengel had decided to keep Mantle out of the lineup. Several beers later, another toast went up when Henry Aaron came to the plate to face Yankee right-hander Bob Turley, with the Braves trailing 2-1 in the top of the seventh.

Nobody had ever had such a great Series so quietly. Aaron had hit safely in all five games with two home runs, but Turley handled him in his first two at-bats of Game 6. He struck him out on a curveball in the second inning and got him on a ground ball in the fourth. That had lowered Henry's average to .380 in the Series, swinging the bat so well that keeping him off base twice was a moral victory. "I was seeing the ball well," Henry said, and he didn't need to say any more than that.

All season long, Aaron listened to critics call him an undisciplined free swinger. The way the chorus made it sound, you'd think Henry would try to drink a High Life with the bottle cap still on. But Turley knew Henry had a very good knowledge of the strike zone. Henry laid off and Turley fell behind in the count, 3-1. Aaron was the leadoff guy and Turley still led by one run. This was a fastball count. There would be no secrets, no surprises. Turley was nasty -- broad shoulders, thick trunk and thighs, and a loose arm -- he was just the kind of fire-throwing short arm the Yanks built their firing squads around. No need to dime Henry -- Turley reared back and challenged him with a letter-high fastball ... and Henry cracked a gunshot that sounded like Mickey Mantle at his best. The ball was out of the ballpark faster than Eddie Mathews could pound a beer. It was the hardest ball Henry had hit in the Series, a home run to left-center field over the 402 mark. Some estimated the ball traveled 425 feet. New York partisans said the only right-handers who hit a ball that far in that direction were Joe DiMaggio and Hank Greenberg. All that mattered was it tied the score, 2-2.

But leading 3-2 in the ninth, Turley walked Mathews with the tying run to bring Aaron back to the plate. The Casey at the Bat moment of the Series had arrived. Once again, there were no surprises, a fastball pitcher against a fastball hitter, the game and the Series in the balance. Turley was covered in sweat, his heavy pinstripe flannels hanging off him like the branches of a tree. Henry cradled his lumber and expected a first-pitch fastball. He got it and took a violent rip, fouling it straight back for strike one. The crowd reaction at Yankee Stadium told the story of the emotion. The fans in Milwaukee pounded their beers on the tavern bars in frustration and anticipation. You could have called in the fielders and let them take a knee. This was man against man.

Turley reared back and threw another fastball. There was a little something extra on it, so quick that it made the previous pitch look like a changeup. Henry flinched. He never flinched. That's how strong Turley's arm was. Plate umpire Jocko Conlan’s call sounded like a Supreme Court judge banging his gavel. Strike two!

Aaron never stepped out of the box. He just wanted the next pitch. He was always a guess hitter and admitted so. He had seen all of Turley's stuff and he knew there was no way Turley was going to throw him a fastball for the third consecutive time. But as Henry Aaron's Alabama stride style forefather Piper Davis once bellowed, "Element of surprise, my dear brother!" Turley stunned Henry when he did just that. The bat never moved. Jocko Conlan called strike three. Nobody -- nobody! -- managed to take the bat out of Henry's like that. "He threw me a beautiful pitch – a fastball about at my knees," Henry said. "I was expecting something inside. I was sore at myself, not Turley."

There would be a Game 7.

When the Braves trudged into the clubhouse with worried faces, Haney walked into the room and answered the question before anyone asked. "Burdette tomorrow," he announced.

The writers scurried to Lew Burdette's locker. He had the calm demeanor of a man who already knew he was pitching Game 7 of the World Series at Yankee Stadium. It was the single greatest plum in all of pitching, but there was a catch. Burdette would have to come out on two days' rest, which even in days of the four-man pitching rotation was uncommon. The short rest didn't bother Burdette one bit, or at least that's the way he made it sound.

Somebody wanted to know if Burdette was a better pitcher now than he had ever been. Lew's big eyes lit up and a big sarcastic smirk came over his face. He looked a little demented, unstable, but that was part of the act. At least people though it was part of the act. "Yeah," he said. "I'm bigger, stronger, and dumber."

-- Excerpted by permission from Bushville Wins! by John Klima. Copyright (c) 2012 by John Klima. Excerpt authorized by Thomas Dunne Books, an imprint of St. Martin's Press, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.