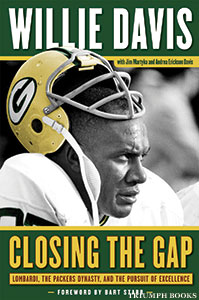

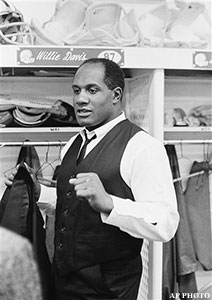

Willie Davis was one of the NFL's strongest, quickest, and most agile defensive linemen and a team captain who helped Vince Lombardi's Packers win five championships. In addition to being enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Davis distinguished himself after his playing career by becoming one of the most respected businessmen in America. He served on the board of directors for Fortune 500 companies, taking part in various foundations, and speaking to audiences of all ages about his experiences. In this excerpt of his autobiography Closing The Gap: Lombardi, the Packers Dynasty, and the Pursuit of Excellence, Davis explores the racial dynamic of being a black player for Green Bay in the 1960s.

There were four of us black players, which was more than several other teams in the league had in their organization.

I would say that nobody had more impact in creating diversity in the NFL than Coach Lombardi. It was partly because he took a new approach, almost playing ignorant to any kind of racial tension in the league. He didn't buy into debates or arguments about his drafting, trading (or in the case of Willie Wood) letting black players walk on. Right from the start, he treated us as equals, just players competing for a spot on the team. He chose not to see color in an era where most chose to look the other way in terms of blacks. It was as if he felt the best way to fix the problem of segregation and racism in the league was to actually pretend it didn't exist -- at least to us.

The other impact he had on the issue stemmed from his success. Coach Lombardi stayed true to his belief that the best players would earn the starting positions on his Green Bay Packers team and that was final. It didn't matter what school you came from, how successful you were in college or the pros in previous years, your time and experience in the league, or your race. If you were the best man and gave him the best chance to succeed, you would earn the starting spot. With the field wide open like that, those blacks that were on the team were truly given an opportunity to let it all out and work hard. As such, many of us during the next few years became contributing players.

And we won.

It would be interesting to have seen how the issue of blacks in the league would have faired if we didn't have as much success as we did. That probably helped diversity in the league more than anything. Coach Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers had so much success during the next eight years -- adding more and more black players each season -- that the rest of the league knew they had to keep up. It was as if the owners took a look at Coach Lombardi's formula and said, "Hey, I gotta get some of those!" Pretty soon, all the teams opened up shop, allowing all positions on their teams to be earned by the best competitors.

Coach Lombardi never really talked to any of us about his true feelings on the issue of black players. But he gave us enough to know how he felt about it. We never really understood why he was so open while other coaches and managers weren't, but we thought part of it might have to do with him being a tremendously dark-skinned Italian. He had experienced his own forms of prejudice, or so we heard, especially when arriving in Green Bay, a town that wasn't used to blacks, Italians, or really anyone other than Polish, German, and some Scandinavian. It wasn't aggressive prejudice by any means, but when he first arrived, Coach Lombardi was not a popular choice to take over the franchise and he received some backlash. Sometimes in the world of sports that backlash can get ugly. At first, the fans were more inclined to run him out of town, and sometimes there are fans that get a little too involved and their actions and words go too far.

I knew that I was going to have a fair shot in Green Bay, which eased a fear I had in coming over from Cleveland. In Cleveland, diversity wasn't much of a problem. It was a city that was fairly integrated with a professional football team that was fairly integrated for its time. Plus, our best player, and arguably the best player in the league, was Jim Brown. Race wasn't an issue.

I was worried that wouldn't be the case with the Packers. That being said, I can say with all honesty that I was never insulted or called any kind name by anyone in the Packers organization -- relating to my race at least! There were some players that I could tell were a little more uncomfortable at first than others, players who worked with you in practice and then went their separate ways once the pads came off, but they kept quiet. Then, there were players like Bart Starr who went above and beyond to make the black players feel comfortable, to feel like we were part of the team. During the next couple of years, it became the norm in Green Bay.

That was partially because of Coach Lombardi's philosophy of fairness. It was partially because nothing brings a team together more than winning. It was also partially because of our environment -- the city of Green Bay and its people -- the greatest fans on the planet.

I feel awful saying it now, but I expected it to be bad. This was the Siberia of football, and last I had heard, there wasn't a booming black population in Siberia. I heard that there were literally a small handful of black resi- dents in the city of Green Bay, less than 100. That constituted less that 1 percent of the city's entire population. Its reputation was that of a small town with a redneck population that was just fine staying behind in the times. One of the jokes floating around the league at the time said it all.

"Green Bay? Well, you know you can put shit on your shoes and still go to the formal."

That's what people thought of a town they knew nothing about. And for us black players, we assumed the reason there was such a small black population was because they simply didn't want us there. That's the only reason, I thought, that African Americans wouldn't settle there. Other Midwestern cities, including Cleveland, were experiencing significant growth in pockets of blacks. There was still a great deal of segregation in these cities, like Chicago, Minneapolis, and even Milwaukee, but there were at least communities where local black residents could feel comfortable. I assumed, as did the other three black players, that if the black population hadn't made it in Green Bay, there must be a significant reason. I feared that we four black players, who somebody joked made up 4/5 of the black population in the city, would not be welcomed.

I was dead wrong.

With the exception of a couple of incidents between guys being guys at the bar, there was no other trouble. To say I was surprised is an un- derstatement. At a glance, Green Bay was very similar to many of the cities I had seen in the South, where not just segregation, but blatant racism still ran rampant. It was the state of the small town back in the early 1960s. There were indications that times were changing, but not rapidly, and not in small towns. As I said, I expected the worst, and instead, what I experienced most was curiosity.

There was some hesitation among the residents to approach me or any of the other black players. We were always met with stares and whispering. But, there was something unusual about it. It didn't feel cold or malicious. It felt more like trepidation. I began to realize that a lot of these folks did want to talk to us, but they were uncomfortable. They didn't know how to approach us.

I was told by many residents, usually after having to gently nudge them into a conversation, that I was not only the first black person they had ever talked to, but also the first they had ever seen in real life. As we talked, they would stare at me from head to toe, fascinated by how different I looked compared to the pale white population of the North. I could tell they didn't want to be too obvious about their curiosity, but they often failed miserably. I swear there were times I almost expected them to ask if they could touch me!

With each conversation I had with a local resident, I could see an enlightenment start to form in their eyes. They had no idea about black people except for what they saw on TV, which at that time was typically even more negative in its representation of the black community. They had no real life experience with black people out here and they were perplexed and fascinated by us. They were also innocently naïve.

"Maybe all those things I heard about you people aren't true," was a rather common phrase I heard in the beginning.

It wasn't something I was upset about or even took the wrong way because as I soon found out, beyond their shyness and inexperience, the residents of Green Bay were some of the nicest people in the country.

The longer I stayed there and got out in the community, the more comfortable the residents got in talking with me. Not only were they fascinated by me and the other black players, they all wanted to be our best friends. I can't tell you how many times I had a beer bought for me or how many times bar or restaurant patrons argued to see who could sit next to me. I also had dinner invites to their homes on almost a daily basis. Many times, I accepted.

The race issue actually led to more humorous moments than anything. In a long-standing tradition, as Green Bay East prepares to face off against Green Bay West in one of the oldest high school football rivalries in the country, they will invite the captains of the Packers team to give a speech. They called it their "color day" because all the players wore their uniforms and all the students wore the team colors. It was yet another example of a community that valued its traditions, and I was glad to take part along with Bob Skoronski, the offensive captain.

As we were introduced, I was met with extra long stares and even some whispering mixed in with the applause. When I told the crowd, "It's a real pleasure for me to be here for your color day," the whispering turned to polite laughter and the cheering got louder. In fact, the crowd went nuts. It didn't hit me why right away, and then Bob told me what I said and how this innocent crowd probably took it. All I could do was smile and laugh along with them, another chapter in what would be (and still is) a long-standing love affair with the Green Bay fans of all ages.

-- Excerpted by permission from Closing The Gap by Willie Davis with Jim Martyka and Andrea Erickson Davis. Copyright (c) 2012 by Willie Davis. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase at Triumph Books, Barnes & Noble, Indiebound and Amazon.