During the bloodiest years of the civil rights movement, Bear Bryant and Joe Namath -- two of the most iconic and controversial figures in American sports-changed the game of college football forever. Bryant was the legendary coach in the South who was facing a pair of ethics scandals that threatened his career, and Namath was a cocky Northerner from a steel mill town in Pennsylvania. Together they led the Crimson Tide to a national championship. Here's an excerpt from Rising Tide: Bear Bryant, Joe Namath and Dixie's Last Quarter that details Bryant's arrival in Tuscaloosa as the new coach in 1957.

The new coach had arrived at Friedman Hall early, moving to the front of the deep, narrow room and repeatedly glancing at his watch. He was not about to begin early, and he assuredly would not start a second late. Tardiness for him was the sign of a deep moral failing, an unforgivable character flaw. "It reflected sloppiness and a lack of commitment," Bryant biographer Keith Dunnavant wrote.

Finally it was time.

"How many of y'all have girlfriends?"

They were football players, weren't they? Almost all of them had girlfriends, some more than one. Maybe the new coach was just asking a friendly question, a prelude to some clever down- home southern bon mot that would break the ice and get everybody loose and relaxed. Get the new regime off to a good start.

"Well, all y'all who raised your hands might as well pack your bags right now, 'cause you won't have the time to become football players."

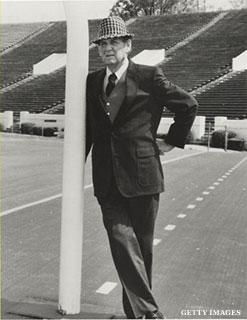

No one laughed. Paul "Bear" Bryant's face was only just beginning to develop a crease or two, still decades away from its familiar deeply lined look -- almost like a sheet of paper that had been crushed into a tight ball then smoothed into a flat sheet again. In December 1957 Bear was still close to his physical prime. He was forty-four years old, almost six-four, roughly 220 pounds, and ruggedly handsome. Everything about him seemed big and powerful -- high forehead, large ears, wide powerful shoulders, thick hamlike hands, sturdy legs. He looked like a coach who could get physical with his biggest players -- really get down without pads and go one‑on‑one with a guard or a tackle and win. He looked it, he could do it, and on occasions when he wanted to make a point, he did it. Even in an expensive tweed suit, a white shirt, and a Countess Mara tie, there was nothing about Coach Bryant that breathed a trace of softness or suggested he couldn't kick the ass of any man within hollering distance.

If there was anyone who doubted that statement, one look into his clear, cold blue eyes would set them straight. He seemed to look at the world with his chin slightly tilted down so that his eyes were skewed up, forcing him to furrow his forehead. It wasn't a calculated expression, but it had a chilling effect. Richmond  Flowers Jr., who was recruited by Bryant, recalled that when you talked to Bear you tended to look up at him and he tended to look down at you. Others who knew him agreed: He had a gaze that was difficult to meet, the kind of penetrating intensity that made a man afraid to look into his eyes directly because it might be interpreted as a challenge, and fearful to look away because it might be taken as a sign of weakness.

Flowers Jr., who was recruited by Bryant, recalled that when you talked to Bear you tended to look up at him and he tended to look down at you. Others who knew him agreed: He had a gaze that was difficult to meet, the kind of penetrating intensity that made a man afraid to look into his eyes directly because it might be interpreted as a challenge, and fearful to look away because it might be taken as a sign of weakness.

On the morning of December 9, 1957, every player crammed into a classroom in Friedman Hall, the athletic dorm, was looking at Bryant. They had heard the stories about the coach -- the tales about Junction Station in Texas, his take‑no‑prisoners method of coaching, his record of turning losing programs into winning ones. But they had not seen him in the flesh until that moment. Now, sitting in classroom desk chairs, standing in the aisles and crammed against the walls, some dressed in khakis, penny loafers, argyle socks, and letter jackets, others in slacks, button- down shirts, and V‑neck sweaters, they waited for a sign of what was to come.

He talked a little about himself, about why he left Texas A&M, a team that had fallen just a few plays short of winning a national championship, for a team that was setting new records of futility at a proud football school. He had come to Alabama, his alma mater, for one reason, and it wasn't money. No, he said, "I could buy or sell any one of you. I came here to make Alabama a winner again."

And that meant a new philosophy and a fresh start for everybody. He made a guarantee and a promise. "Everything from here on out is going to be first-class, which includes living quarters, food, equipment,  modes of travel. And my staff and I are going to see that you play first-class football." He said that he was only interested in first-class boys on his team, the kind who regularly wrote letters to their parents, always used "yes, sir" and "no, ma'am," said their prayers at night, and went to church on Sunday. He demanded boys who took pride in how they looked and how they acted, ones who were excited about representing a great school and determined to represent their family and hometown with real class.

modes of travel. And my staff and I are going to see that you play first-class football." He said that he was only interested in first-class boys on his team, the kind who regularly wrote letters to their parents, always used "yes, sir" and "no, ma'am," said their prayers at night, and went to church on Sunday. He demanded boys who took pride in how they looked and how they acted, ones who were excited about representing a great school and determined to represent their family and hometown with real class.

If a boy knew he did not fit Bryant's definition of a first- class player, if he wasn't ready to give maximum effort, Bear had some advice. "If you're not committed to winning ball games, to making your grades, go ahead and get your stuff and move out of the dorm, because it's going to show. Pull out so we can concentrate on the players who want to play."

Beyond that, Bear didn't talk about the x's and o's of football. There would be time for that, and time for them to get to know him and him to get to know them. Right now, he said, "I don't know any of you and I don't want to know anybody. ... I'll know who I want to know by the end of spring practice."

-- Excerpted by permission from Rising Tide: Bear Bryant, Joe Namath and Dixie's Last Quarter by Randy Roberts And Ed Krzemienski. Copyright (c) 2013 by Randy Roberts And Ed Krzemienski. Published by Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY.. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase by the publisher and Amazon.