You do not spend much time around Kirk Gibson without encountering the glare. It is, in fact, the first thing you notice about him, peering like darkness from beneath his red cap, surrounded by a day's growth of stubble. The glare is softened perhaps by the fact Gibson is now 54 years old, but it is chilling nonetheless. As a player the glare seemed fueled by some inner volcano that erupted at the slightest failure. The image of him then was as a wild-eyed lunatic seething over every fly ball to center field, slamming his helmet, throwing his bat and stomping off to the clubhouse to channel his rage on a hapless folding chair.

As a manager his eyes do not boil. He does not throw chairs. He says he is not that man anymore and yet the glare lingers, leaving in the air a hint of discomfort that recently caused the team’s CEO Derrick Hall to turn to his general manager Kevin Towers and jokingly say: “I dread the day we would ever have to fire him.”

Not that they have to worry. Gibson is doing something no one dreamed possible: He has turned the Diamondbacks into winners. They sit in first place in the National League West, all but certain to win the division with many of the same players who lost 97 games last season. It might be the most remarkable story of this baseball season, even if it reads like a predictable sports script: intense former player takes over a broken-down ballclub and by the force of his fiery will leads it to a championship.

But it is more complicated than that. Just as the man is more complex than the glare would have you believe.

"I just smile and laugh when all people think they know about Kirk is the way he was as a player," Gibson's friend and Diamondbacks bench coach Alan Trammell says. "There was so much more to him, he just didn’t let anybody in."

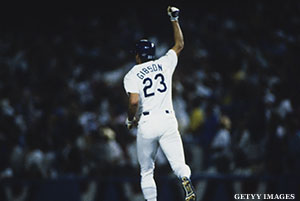

In those days Gibson was known as much for his refusal to sign autographs and his belligerence with journalists as for the home runs he hit. Several sports writers from those days say he was the most difficult athlete they ever covered. Yet many of those same reporters wrote glowingly of him when he pulled a mediocre Los Angeles Dodgers team to the World Series in 1988. And those spurned fans nonetheless leaped to their feet in Game 1 of that Series when he limped to the plate with a pulled left hamstring and a swollen right knee and somehow hit a game-winning home run with a lunging, one-handed swing. It was a shot so unimaginable it spawned two of the greatest broadcast calls ever: (Vin Scully, "In a year that has been so improbable the impossible has happened" and Jack Buck, "I don't believe what I just saw.")

Still the player was hard to grasp. Several of his Detroit Tigers teammates said they wearied of his tantrums. Others stayed clear. What was the point of angering a man so tormented by imperfection? Most agree his temper was a flaw born of a compulsion to win. And so he was forgiven his tempestuousness because, after all, winning makes everything better.

It also helped that Tigers manager Sparky Anderson recognized Gibson's competitiveness but understood the baseball skills were not refined in the years Gibson was an All America wide receiver at Michigan State. He famously told the young Gibson to sit next to him on the bench during games and slowly over two stints with the Tigers Gibson came to build an understanding of the sport that matched his fire off the field. By then injuries had ruined the player who crushed booming home runs. He retired in 1995 then returned in 2003 as a bench coach for Trammell who was then managing the Tigers. Last year he was named interim manager of the Diamondbacks. Over the winter the job became full-time.

He has matured, people who know Gibson say. But the intensity lingers. In trying to describe this, his third base coach Matt Williams fumbles for words before lunging forward with his eyes wide, mouth open and fingers radiating from his forehead "like that" he says.

"The unwavering desire he has," Williams continues, clearly frustrated to quantify an emotion he lives every day, "it's, well, unwavering. I just can't find any other way to say it."

Williams stops and looks around. Several of the D-Backs players are in the batting cage beneath the stands taking a second round of batting practice. At some point they will set the pitching machine to spit out curveballs, something teams rarely do during the season when hitters are trying to maintain their swings.

"He has them believing they have a chance to win every night," Williams says. "They feed off of Gibby's intensity."

The fact is, Gibson has changed, or maybe he is working more to show that hidden side Trammell talks about. The Arizona players do not see their manager as a raging madman. For instance, catcher Miguel Montero calls the intensity "Gibby being Gibby," before adding: "He lets us play, man."

Gibson has not torn into them after losses. He hasn't cursed or thrown chairs or bats or anything. The team is so young most of the players don't even know what he was like as an athlete. All they really understand about his career is the home run in 1988. The only remnant of those days is the glare.

"He lets you know you know he's mad in other ways," pitcher Joe Saunders says. "It's like disappointing your parents when you walk in the door."

The Diamondbacks had been losing when they arrived at Washington's Nationals Park three weeks ago, their streak of losses up to five in a row and there was some concern as to how Gibson would handle the downturn. This was his first time in the pressure of a pennant race as a manager and the player at times like this was often at his most volatile. But when reporters found him in his office a few hours before the game, already dressed in uniform with his cap pulled over his eyes, he seemed relaxed. He smiled slightly through the stubble and glanced at a reporter he sees every day, chuckled and said in a voice that always seemed a little higher-pitched than his look that the man was "strange."

He paused then smiled more.

"I know it, so am I," he said.

It was an awkward moment, a joke that didn’t quite work but nonetheless showed a very different Gibson from that of the 1990s. The losing would not throw him into a frenzy. When asked how loose he seemed, he replied: "I’m tight every day."

"I'm serious," he added. "When the game starts and you are a player you have a feeling about yourself. I still have that regardless. We’ve been playing decent. There’s no sense we are getting uptight or nervous or agitated. I haven’t seen signs of that. It would be out of character for us."

That night, after the Diamondbacks lost their sixth in a row Gibson did not thunder into the clubhouse and yell. He did not complain about the fact they couldn't hit Nationals pitching. Instead he told the players to skip batting practice the next day,maybe a lighter approach is what they needed.

And when they won that next night he cancelled batting practice again. Then when the winning continued for another night he scrapped it once more and again an evening later as the wins piled up.

"I will never forget how hard it was to play this game," Gibson later says in a rare moment of introspection. He is in his office, talking about trying to pull the D-Backs from their slump and suddenly the words start spilling out. "There's a lot of good highlights that are played about me ad-nauseum but the reality of this is I was an average player who did some good things at the right time. I had a lot of crappy times. I totally understand and relate to what they are going through. They over-try and get frustrated. I think the longer I am in the game that can be counterproductive. I used to be really intense and went as hard at things as hard as anybody and reacted to failure as violently as a person can do it.

"And this year..." he continues before stopping. He thinks for a moment the glare still there before continuing, "I've just done a lot of reading over time and try to see how people approach those situations and just how I've become -- I just try to be understanding."

He is asked about the tantrums, the throwing of the helmet "and the kicking of the bat?" he says, nodding solemnly.

"That was part of my game. I played hard and maybe somewhat that was part of the football that was still very prevalent in me, because that's what you do in football when you get frustrated: You hit people. So I came into the game, I was pretty aggressive and maybe that intimidated some people, added an edge. But I think I'm better at saying what I have to say in a better way."

Then Gibson begins to speak about his coaches -- a collection of former all-stars in Trammell, Williams, Don Baylor and Charles Nagy -- saying he wants them to offer their opinions, to not be afraid of him and that he has to understand they have something to offer. He says the same goes for players who are free to come in and make any comment they wish, flattering or not.

"Anyone know what a scotoma is?" he asks and everybody in the room stands still, expressions stunned because Kirk Gibson is asking if anyone has ever heard of a "scotoma." Finally he says: "Scotoma's like a blind spot, so when you look at things through my eyes ... like you could look at something and I wouldn't see it, but to you guys it might be very clear. To my staff and my players it might be very clear So you have to search that out. That's the kind of approach I like to take."

A moment later Gibson clears the room. He wants to prepare for the game. This is the most anyone will be getting from him about what lingers behind the glare.

It was early in the Diamondbacks spring training this year and hail was falling. Elsewhere, other teams' managers were scrapping morning workouts, telling their players to stay inside. It was cold, it was wet. Nobody wanted to be outside. Everybody, that is, but the Arizona Diamondbacks, who were on the field, gloves in hand, running through drills even as the icy rain pelted down around them.

Kirk Gibson wasn't leaving a moment wasted.

He had obsessed over this spring training, planning it for months, calling Towers almost daily in the winter with questions about the schedule, their conversations stretching for 30 and 40 minutes. Would they have enough fields? Was there time for a workout and a trip across town from an exhibition game?

After awhile Towers didn’t bother to say hello when Gibson's number appeared on his phone. Instead he just said: "Gibby, is this going to be about spring training again?"

But there was a culture that needed to be changed and Gibson was going to take every moment of February and March to do it. For too long, he told people in the organization, the Diamondbacks had forgotten about fundamentals. The approach was wrong. People weren't serious. Several times he called meetings with his coaches, having everyone fly into Phoenix for discussions about the spring plan. He and Towers called for a meeting of the entire organization that included every minor league manager, hitting coach, pitching coach, scout, minor league team broadcaster, general manager and public relations man and laid out a philosophy for how he wanted the Diamondbacks to play. Much of this had to do with things as mundane as how to take leads off first base, how to run with two outs or how catchers throw to second, but there was going to be a unity in how everything was taught so when players began trickling up to the major league team there would be no adjustment, they would fit exactly what Gibson wanted them to be.

Spring training was nothing like what the Diamondbacks had ever experienced. It started with the weight room, which Gibson, Towers and the coaches hit every day at 5:30 a.m. "You didn't want to be the one who didn't do it," says Nagy the pitching coach. Soon the players saw the coaches showing up early and arrived earlier themselves. Once practice started the workouts went on for hours and the instruction was endless -- rundowns, pickoffs, relays from the outfield. In the afternoon exhibition games, the D-Backs were terrible. At the time it led to a concern the team wasn't very good. Now looking back, Diamondbacks executives realize that GIbson worked the players so hard in the morning they were exhausted by game time.

And it wasn't just the workouts. There were lectures. Every few days a different coach stood before the team and talked about his specialty. One day it might be Baylor the batting coach talking about situational hitting or Nagy discussing pitching with runners on base. Once Gibson allowed a group of Navy SEALs to address the players. The SEALS talked about Afghanistan and those times on their missions when things start to go wrong. They said they had an expression for such times. They call it "DWI" or "Deal With It." Gibson liked that and soon "DWI, Deal With It," appeared on the clubhouse whiteboard.

Sometimes Gibson didn't take the players onto the field, leading them instead to a meeting room where a screen was pulled down and films from the exhibition games began playing. "This is constructive, so don't be sensitive," Gibson advised before launching into diatribes about the right and wrong ways to approach an at-bat.

All of this comes off more like a football training camp than a gentle spring training and in a way it does seem the old football player spills from Gibson. But it was also the only way he knew how to do it. For while a lot of this was football, a lot of this was also Sparky. Trammell can still remember the game in Baltimore back in the 1980s when the Orioles executed a perfect relay on a ball hit to the left field fence -- each throw crisp and to exactly the right player. Watching from the dugout, Sparky was so taken by it that the next day he took the entire Tigers team to the outfield, all the way to the fence and lectured them on the proper way to make a relay from the outfield wall.

"It's just imbedded in us," Trammell says. "It's the way we were brought up in the minor leagues and now it's Kirk's philosophy too. I think we are thankful we had Sparky throughout our lives, we were just taught a little bit differently. With Sparky, the Bible was the scoreboard. The scoreboard told you what you needed to do, what base you needed to throw to, where you needed to be. And you might say 'Oh, it's so easy,' but you see people make mistakes all the time. There are times when the scoreboard tells you to be aggressive and there are times when it tells you not to be. This is all we know. This is what we grew up with."

Often around the D-Backs you hear the phrase "old school" or "hard-nosed" when folks talk about Gibson. People around the team like to say how the team "grinds out" its victories and there is a lot of truth to this. Once the players adapted to the new philosophy -- an event that most say occurred after a team meeting in Los Angeles when rather than berate the players Gibson told them to "look to help each other out" -- the wins did start coming and they have often been grueling affairs pulled out with a late run. The D-Backs play with such intensity it is easy to see them winning a playoff series in October even without the pitching of the Phillies or Milwaukee's powerful lineup.

But the temptation is also to believe that Gibson is all about managing by what baseball people call "the gut," relying on instinct rather than the more modern statistical analysis. Those who know him say the truth is actually something quite different. He absorbs everything, filtering through matchups and rows and rows of numbers on the laptop he keeps open at all times on his desk. Nearly every move in the game is calculated. Little that happens comes as a surprise to him.

"He's got the whole game planned out before it starts," Towers says.

In the future, this might be what makes the difference for Gibson as a manager. At some point the intensity might wear thin with players, as the spring training bootcamps will be too much. But there is no substitute for preparation. His mind is what will ultimately sustain him.

By the fourth night in Washington the losing was long forgotten. Arizona was at the start of a streak in which it would win nine in a row and essentially destroy any race for the division title in the National League West.

Gibson was feeling good. And so while his coaches lingered over throwing and hitting schedules and most of his players still lingered in the clubhouse, he hobbles down a flight of stairs from the clubhouse and to the indoor batting cage. His knees are worn down, a few years ago he had surgery on his neck. He hadn't swung a bat in four years, he said, mainly because of the neck surgery, but suddenly he is struck with the desire to do so.

He lifts the cage's netting, steps inside, picks up a batting tee, places a ball on the top and swings. THWACK. The ball flies into the netting. Gibson reaches down and picks up another ball. THWACK. "Double down the third-base line!" he shouts.

Given the wobbling stance and the way his feet stumble around the cage, this must have been what it looked like that October night in 1988 when he took a few lumbering warmup swings in the Dodger Stadium tunnel before heading out to make history.

A few players gather and watch as their manager keeps smacking balls off the tee. THWACK. "Home run!" he cries. For a moment the glare is gone. The players look away and stifle chuckles. Gibson smiles through the stubble. Then the smile disappears. He calls a player over. "Let me show you where you hit the ball on the bat ... " he says.

Kirk Gibson is serious again. In three hours a game will start, a game he expects to win, and there's so much to be done. He looks up, spots a visitor who is not a player and glares. It is not an unfriendly look but it is not welcoming either.

It's just Kirk Gibson.