This is the first in a series of Tuesday essays by columnist Patrick Hruby.

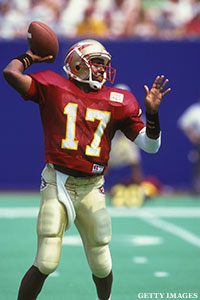

Even today, he still has the jersey, red and faded and unremarkable, a reminder of the day his dreams went awry. He wanted to be a quarterback. He always had been a quarterback, and damn good one, too: winning the Heisman Trophy, leading his team to the national title game in the Rose Bowl, appearing on the cover of a video game, beating defenders with his arm and his legs. Teammates described him as a leader, disciplined and competitive, mature beyond his years. Heck, he even looked the part, handsome and clean-cut, with showbiz-dark features and politician-grade hair. On the field and in his gut, Eric Crouch was perpetually under center, the ball in his hands, and when he showed up at the 2002 NFL draft combine, he hoped to be evaluated as such.

Instead, they handed him a red jersey.

No. 13, it read.

RB, it read.

At Nebraska, Crouch had excelled in a option offense, pitching and running and throwing, taking hits and giving them. The option can’t work in the pros. He stood six feet tall, taller than Hall of Famer Sonny Jurgensen, as tall as Super Bowl-winner Joe Theismann. Too short to play quarterback. Twenty-two teams spoke to Crouch, and each one thought they knew what was best. We think you might make a good receiver, said the Oakland Raiders. We think you’d be an awesome safety, said the Tennessee Titans. Crouch took it all in, an extended elegy for his athletic identity, one deflating job interview at a time. In return, he said everything he knew they wanted to hear, about fitting in and getting a shot and doing whatever it takes. He had a fiancé and an infant daughter and an uncertain future ahead of him. He was 22 years old. He wanted very badly to belong. So he put on the red jersey, No. 13, and drilled with the running backs. With the defensive backs. With the receivers. And with the quarterbacks as well, just in case. He ran a killer 40.

A few months later, the St. Louis Rams picked Crouch in the third round of the draft, made him a instant millionaire. They asked him to play receiver. He was elated. And miserable. He would spent the next decade trying to get back under center, and his life in football would never be the same.

In other words: he would never be Tim Tebow.

"I think I could have been a great NFL quarterback," says Crouch, 33, now a playground equipment vendor. "I battled some injuries. I took a lot of bad advice. I played a lot of different positions. If I could change one thing, I would have been pretty forthright about saying that quarterback was going to be my position. I'm going to play quarterback or not play at all."

When dissecting Tebow's wild ascension to national folk hero status and an unlikely perch atop the AFC West, most discussion focuses both on what the Denver Broncos quarterback can do (win games; inspire teammates and Internet memes; give John Elway angina; run -- not scramble -- as if controlled by a real-life version of "Madden NFL's" truck stick) and what he can’t (drop back like Peyton Manning; read defenses like Tom Brady; throw a pass half as pretty as Jeff George and JaMarcus Russell; throw a pass half as pretty as the median frat brother on the average intramural flag team). Mostly ignored, however, is the importance of what Tebow didn’t do.

Namely, the former Heisman Trophy winner did not enter professional football earnestly agreeing to play fullback.

Or tight end.

Or -- gack – strong safety.

Instead, Tebow believed in himself. Shrugged off the helpful position-switching advice -- read: incredulous derision -- proffered by the likes of Jerry Jones and Mel Kiper, Jr. Didn't sweat an ungainly throwing motion that owes less to Aaron Rodgers than Mr. Rogers. Discounted his inexperience with running a pro-style passing offense. He went all-in on what he did best at Florida -- playing quarterback -- and expected skeptical NFL talent evaluators to follow suit. In doing so, Tebow helped create an opportunity that so many other players like him never had, an opportunity that so many others never had the sheer sanguine bullheadedness to demand.

He got his shot. The ball in his hands.

"I love seeing that," Crouch says. "I feel like I was a very similar type of player coming out of college. But I was never given that kind of opportunity. It says a lot about Tim Tebow to say ‘I know I can play quarterback and I want to play quarterback.’ That is brave for a 23-year-old."

Brave for the Broncos, too. Definitely different. Maybe even a little crazy. Traditionally, this is what happens when the square peg of the talented collegiate option quarterback meets the round hole of the pocket passing-oriented NFL: if a player is lucky, he's hammered into the sport's preexisting template with all the subtlety of King Kong playing whack-a-mole; if a player is unlucky, he's discarded from the toy box entirely. In the 1970s, the Miami Dolphins made Freddie Solomon a wide receiver. In the 1990s, the New York Jets made Scott Frost a safety. The same league that treats transcendent athletic ability the way Countess Bathory treated virgin blood couldn’t find a place for run-pass dynamo J.C. Watts, and drove Heisman Trophy winner Charlie Ward into the NBA's waiting arms.

Beau Morgan, Darian Hagan, Tommie Frazier: talented option quarterbacks all. None played a regular season down in the NFL. Too small. Can’t consistently throw from the pocket. Don’t fit the prototype.

Consider Antwaan Randle El. For him, the pressure to conform came early. In high school. Every school wanted the speedy, dual-threat prep star; most, like Notre Dame, wanted him to play receiver. Maybe cornerback. Only Nebraska and Indiana promised him a shot under center. The Cornhuskers subsequently signed Crouch. Randle El became a Hoosier. The staff believed in him, starting with head coach Cam Cameron. You’re a quarterback, they said. You’ll be our quarterback. That was all Randle El needed to know. "When you hear it from everyone, when you’re backed like that, it makes a difference," he says. Three years into his college career, Randle El was on pace to finish in the Big Ten's career top 10 in both rushing and passing yards; nevertheless, he spent the summer before his senior season learning how to run routes, planning a switch to wide receiver, fearing the NFL would otherwise not have a place for him. The grand experiment lasted all of one game, pretty much fizzling after one play. "I’ll never forget the very first play," Randle El recalls. "We had a run-pass check: if you see eight [defenders] in the box, run the go route. Oh my goodness, we worked on that all week. So the defense brings the safety down. I beat the corner and I'm scot free, running down the sideline. The crowd was so loud. It would have been a wrap."

He laughs.

"Our quarterback didn't check to the pass. I played back and forth at quarterback after that."

Randle El was fortunate: when the Pittsburgh Steelers later asked him to line up as receiver, he already knew how to play the position. More importantly, he bought into the switch. He ultimately thrived, playing 10 seasons with the Steelers and Washington Redskins, even throwing a gadget touchdown pass in the Super Bowl. By contrast, Crouch wasn’t able to make the same adjustment. He didn't much want to. And football -- violent and consuming, brutal and demanding -- is a game of want. Playing quarterback got his motor running, his adrenaline flowing. Playing receiver? Not so much. During training camp with Rams, he would leave work dejected, come home defeated. His daughter would wonder why daddy was so sad and silent. Following a gruesome preseason leg injury, Crouch retired, giving back a $395,000 signing bonus. The Green Bay Packers called. We'll give you a shot at QB. The day before Crouch left for training camp, the team signed Akili Smith. Change of plans. Can you play defense? Crouch quit again, came back, learned to play safety, worked very hard on backpedaling. He latched on with the Kansas City Chiefs, bounced to NFL Europe. He found himself Germany, playing for the Hamburg Sea Devils, watching quarterbacks Ryan Dinwiddie and Casey Bramlett warm up. Hamburg coach Jack Bicknell -- who once coached another too-small quarterback, Boston College’s Doug Flutie -- took notice.

Eric, you sure you don’t want to play quarterback for me?

Crouch laughed it off. He didn’t know if Bicknell was serious, couldn’t remember the last time someone asked him that. Not since college. They never discussed it again. "But every day, I thought about it," Crouch says. "Every day, I watched those quarterbacks warm up and thought, 'That should be me.'"

That should be me. In an indirect and vicarious way, Tebow is playing for Crouch. And Randle El. And all the rest. They’re a fraternity, after all, a league of All-American rejects. They know the sting of being shut out, the frustration of not conforming to type, the cruel finality of thanks, but no thanks. In life, it’s one thing to struggle and fail and learn your limitations; it’s another to have them thrust upon you. They know that Tebow getting an opportunity in the first place is unusual; they grasp that Denver actually tailoring its offense to his unconventional skill set is downright miraculous. The NFL is a passing league. Defenders are too fast, too strong. The option is a gimmick. Option quarterbacks are a joke. They’ve heard it all, from scouts and coaches and talking heads, the white noise of the sport. Even now, with the Broncos atop their division, John Elway seems to regard Tebow with all the enthusiasm of a prisoner of war lauding his captors on videotape. "I don’t know if what Denver is doing can work in the long term," says former Dallas Cowboys coach Barry Switzer, a successful option coach at Oklahoma. "There’s a big question mark there." Crouch understands. He has been around the game, attributes much of his inability to stay healthy as a pro to the numerous hits he took in college. Growing up, Elway was his favorite player.

"I get it," he says. "If every team runs the same system and looks for the same kind of player and they’ve been doing it for years, it’s hard to change. If you have $60 million tied up in your starting quarterback and you run an option play and he blows his shoulder out, the owner is going to go, 'What are you thinking?'

"On the other hand, if you're not using your players' strengths, then you're probably missing out on a lot of opportunities. I commend the Broncos for doing that. I think they’re doing the right thing. You can try to shape someone into whoever you think they might be. But being open and understanding about what a player's strengths are helps the team. If you see a guy is very good in shotgun, put him in shotgun. If he does well running the option, let him run the option."

Randle El agrees. Look at it like this: every year, a handful of NFL teams are happy with their quarterbacks. Most clubs aren't. They don't have a Drew Brees, can't find a Ben Roethlisberger. Nevertheless, they continue to build and plan and draft as if the likes of John Beck and Chad Henne are minor glitches in an otherwise perfect piece of pro passing software, as if the next Elway is about to walk through the locker room door. Wouldn’t it make more sense for some of those squads to give option quarterbacks like Tebow a shot? Wouldn’t it be smart to take advantage of an untapped collegiate talent pool, and perhaps win games in a different way? Apple didn’t trump Microsoft by beating Windows; they became Silicon Valley’s 21st century standard-bearer by creating the iPod and iPhone.

"We've been knocking on the door," Randle El says. "At some point, we’re going to blow it down. You're going to see about 10 teams that have guys like Tebow, guys that can throw the ball and run it. Even if you get a guy that doesn’t work out, somebody else will take a shot."

Another laugh.

"I could be that next guy. You never know. I'm 32 and I can still wing it."

Once a quarterback, always a quarterback. Earlier this year, Crouch came out of retirement to play for the UFL’s Omaha Nighthawks. His daughter is now 12. He has a 7-year-old son. In addition to selling recreation equipment, he works for a medical device company. He isn’t getting any younger. Still, Crouch was excited. He loves football, loves coaching younger players, sharing what he’s learned about offense and defense and, yes, backpedaling. In his very first game, he tore the meniscus in his knee while making a cut, untouched. His season was over. Another unlucky break. Only that's not what Crouch remembers. He remembers lining up behind center, in the shotgun, 10 years and nine surgeries and one red practice jersey after walking away from the Rams, starting his first professional game at quarterback. Just like Tebow. At last.

Near the end of the season, he shared a moment with Nighthawks coach Bart Andrus, a former Titans offensive assistant. You don't have anything to prove, Andrus told him. You started at the highest level. As a quarterback. You can do it.

"It was a tremendous feeling," Crouch says. "I can't even explain it. I had never really been told that."

-- Patrick Hruby is a culture writer for the Washington Times. His work has appeared in the Best American Sports Writing series. Follow him on Twitter @patrick_hruby and contact him at PatrickHruby.net.