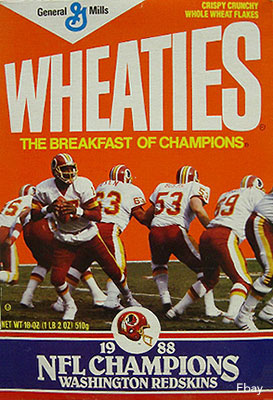

From 1981 to 1992, Joe Gibbs coached Washington to three Super Bowl victories, making the team the toast of the nation's capital, both among the political elite and the city's majority African-American population. Hail to the Redskins by Adam Lazarus features an epic cast of characters: Hard-drinking running back John Riggins; the dominant, blue-collar offensive linemen known as "the Hogs" who became a cultural phenomenon; Joe Theismann, a model-handsome pitchman whose leg was brutally broken by Lawrence Taylor on Monday Night Football; gregarious defensive end Dexter Manley, who would be banned from the league for cocaine abuse, and Doug Williams, the first African-American quarterback to win a Super Bowl. Here is an excerpt:

As he had following their victory in 1983, President Reagan did personally congratulate the Redskins upon winning Super Bowl XXII. Instead of meeting the team on the tarmac at Dulles, he invited them to the White House three days later. But before their trip to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Redskins players and coaches were met by six hundred thousand people in front of the District Building. Amid freezing temperatures, fans gathered on rooftops, looked through open apartment building windows, stood atop benches, hung from traffic lights, trees, and D.C. landmarks just to catch a glimpse of the champions. Snapping the wooden barriers at the base of the dais, rowdy spectators -- thirty-one people were arrested and two dozen others required minor medical treatment -- rushed the stage as players appeared.

"I haven't seen it like this since the hostages came back," said Mike Davis, an official for the city council chairman.

In addition to John Warner, Congressman Steny Hoyer (D- MD), and Washington, D.C., mayor Marion Barry -- who warned the advancing fans, "Somebody’s going to get hurt," and urged "Come on, back up, back up, take two steps back" -- Joe Gibbs, Dave Butz, and other Redskins stars addressed the crowd.

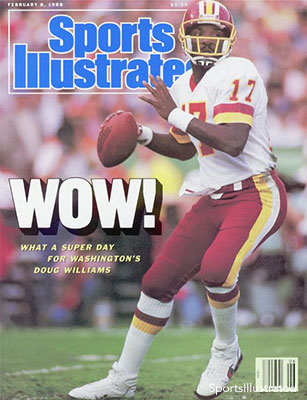

The most exuberant, most raucous cheers, however, were "We want Doug! We want Doug!" People wanted to see and hear from Doug Williams, who limped to the microphone on crutches; his hyperextended knee still ached.

"I consider myself a real, real lucky person," Williams told the crowd. "Three years ago, there was only one football team that gave me an opportunity to play and that was the Washington Redskins."

Williams's humility that day -- he insisted that the game's MVP award "could have been given to a lot of people" -- and the grace he showed when he was benched in favor of Jay Schroeder won over Redskins fans just as much as his tremendous play that season did. And to the African American community the outcome of Super Bowl XXII signified a watershed moment.

"There probably isn't an African American sports fan in America who doesn't remember where he was on that day," former Sports Illustrated managing editor Roy S. Johnson said years later. "Just as we remember where we were when Martin Luther King was killed, where we were when the Civil Rights Act was passed."

But within the Washington, D.C., area, Williams's triumph carried a special meaning. By 1988, the nation's capital was in crisis, with no segment harder hit than the city's African American population.

"White flight" robbed the city of its tax base. The crack epidemic was surging, and "black-on-black" violence would soon plunge the city toward the title "murder capital of America."

The city's once-promising mayor, former civil rights leader Marion Barry, not only struggled to remedy the growing problems, but rumors about his own drug and alcohol abuse had already surfaced.

Even the sports world was not immune. The heart-wrenching death of D.C. metro area hero Len Bias -- the University of Maryland All-American basketball player who overdosed on cocaine two days after being selected second overall by the Boston Celtics in the 1986 NBA Draft -- disillusioned the entire region.

"All of this pride, all of this connection, everyone looking up to [Len Bias] because he's representing many African Americans in D.C. -- and then he dies," said Dr. Charles Ross, the University of Mississippi's Director of African American Studies. "It was almost like, to those black folks in D.C., that he's one of them ... and they can't get themselves together, they're not winners. ...

"So I think Doug Williams came along at a time when many African Americans needed a hero," Ross observed. "As the [1987] football season continued to move forward ... and they get to the Super Bowl, all of this optimism now can be shifted to him. ... Doug Williams really resuscitated that hero component that people were looking for."

The day after the Redskins’ championship rally, Williams visited Howard University, the historically black school located in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C. At Burr Gymnasium, 2,500 students, faculty, and local citizens attended "Doug Day" to see Williams, who spoke to the crowd for forty minutes. Over constant flashbulbs clicking, shouts of his name, and thunderous applause, Williams discussed his similar education at Grambling State, overcoming aches and pains, the media scrutiny he faced, and his performance against Denver. Some of the loudest cheers came upon mention of the scary knee injury he suffered just minutes before rewriting the Super Bowl record books during the game's second quarter.

"When you fell down ... and hurt your leg, we went down, too," D.C. Council member and civil rights activist Frank Smith Jr. told Williams in front of the crowd. "And when you rose up, we rose with you."

-- Excerpted by permission from Hail to the Redskins: Gibbs, the Diesel, the Hogs, and the Glory Days of D.C.'s Football Dynasty by Adam Lazarus. Copyright (c) 2015. Published by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, IndieBound and iTunes. Follow Adam Lazarus on Twitter @lazarusa57.