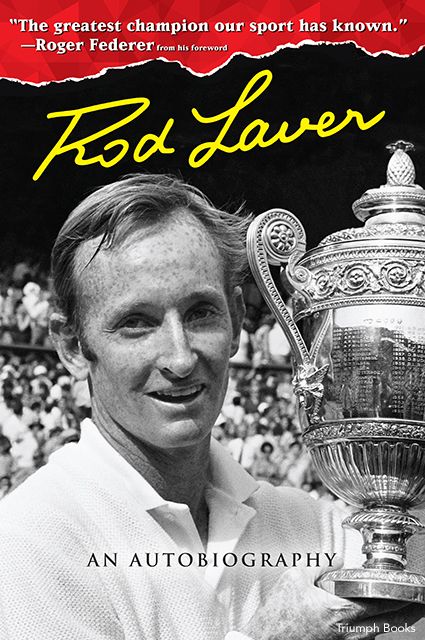

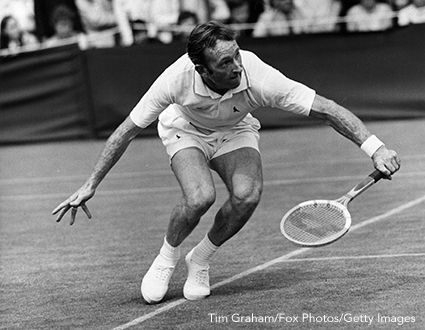

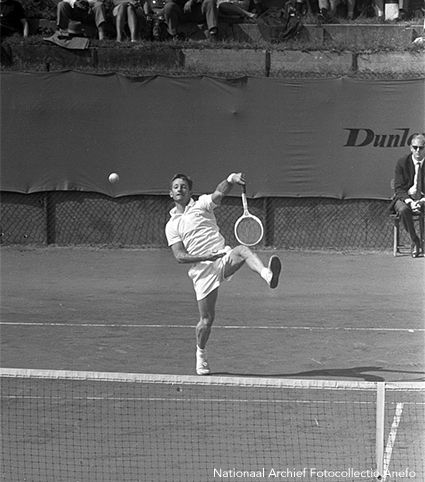

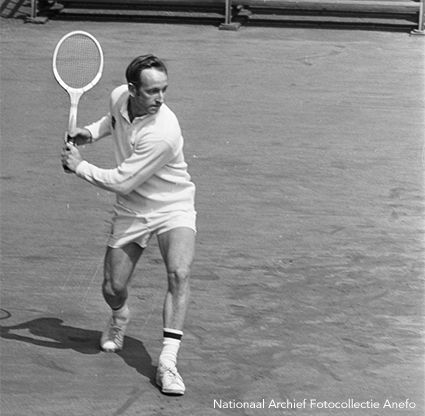

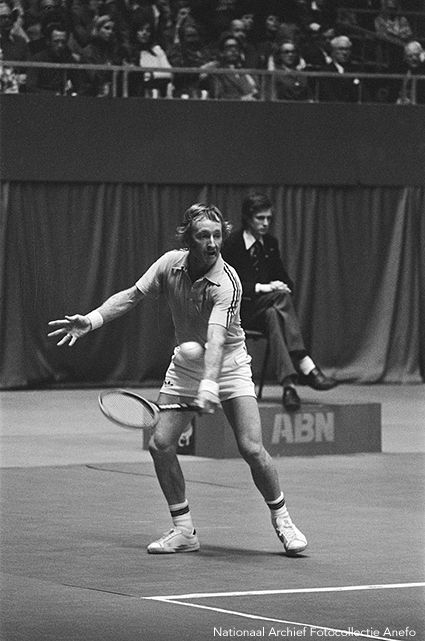

In 1962, Rod Laver became the second man to capture the Grand Slam -- winning the Australian, French, Wimbledon and U.S. titles in a single year. At the time, only amateur players were allowed to compete in those Grand Slam tournaments. The "open era" of tennis, which allowed professionals to play those events, began in 1968. Laver decided to turn pro in late 1962, meaning he missed five years of participating in the major tournaments. In 1969, Laver secured his second Grand Slam, and no man has done it since. In this excerpt from Rod Laver, An Autobiography, the man known as the Rocket recalls the way 1962 unfolded for him.

My results all year qualified me to be the top seed at the United States championships. The persistent offers from the pro ranks were pleasant, if unsettling, distractions from my preparation to win the US tournament and the Grand Slam. Truth to tell, I was certainly keen to win the Slam, though far from obsessed about it. "Philosophical" best describes my state of mind when considering the prospect. If I achieved it, great. If not, the sun would still rise tomorrow.

Through Ken Rosewall, the IPTPA (the professionals' governing body) made no secret that I was top of its wish list, and with a war chest of £67,000 they were also targeting Roy Emerson, Swede Jan Eric Lundquist, Mexico's Rafael Osuna, Manuel Santana of Spain, and Germany's Willie Bungert and Christian Kuhnke. I told them once more that I'd be making no decision about whether I would or wouldn't turn pro until after the U.S. titles and Australia's Davis Cup defence in December. The ageing professional Pancho Gonzales also offered me a minimum $50,000 and a maximum $100,000 to take him on in a one-year head-to-head pro tour at venues all over the world. I turned him down for the same reason that I'd said no to the IPTPA, and, more than that, I had reservations about dealing with the temperamental Gonzales.

I hoped coming out and stating that I was not interested in becoming a professional just yet would earn me some peace. No such luck. The approaches from the professionals kept coming, as did persistent queries from reporters pressing me about what my future held. The press even got on the blower to my father in Gladstone. Dad played a straight bat, giving nothing away even though we had discussed the pros and cons of turning professional many times. "We would like Rod to stay amateur, but it's up to him to use his own discretion," he said. "Actually, it doesn't worry the family in the least one way or the other. We'll leave him to make his own decision. After the excellent year he's had it wouldn't surprise me if a big money offer was made to him, and it would be a big thing for a young fellow not used to a lot of money to turn down a big pro offer. Rod has a pretty true idea of everything. We hope to have him home for a week after the American tournaments and we'll have a family discussion then."

At Forest Hills I was raring to go. I played forceful, precise tennis and had straight sets wins against Elezer Davidman of Israel, Eduardo Zuleta of Ecuador, Bodo Nitache of Germany, and my old Davis Cup opponent, Tony Palafox of Mexico. By taking me to four sets, including a 13–11 second set, American Frank Froehling, who had a booming serve and forehand but a suspect backhand that I preyed on, gave me the contest I probably needed at that stage in the quarterfinals.

I was honoured, halfway through the tournament, to be contacted by the great Donald Budge, who, as one who had achieved a Grand Slam and knew better than anyone the pressures involved, suggested that I might benefit by joining him for a day and a night at a secluded resort in upstate New York where we could relax away from the championship hubbub, have a gentle hit-up together and shoot the breeze. We did all that, and had a meal and saw a movie. It was the ideal way to decompress. I was a bit surprised a few weeks later when I heard that Don had been putting it about that he and I had played a deadly serious match and I had nearly beaten him. I thought, "What!" Don was 47 and a decade and a half past his prime, and our "deadly serious match" was a series of innocuous taps to each other across the net. Don was a bit like that. I think he had trouble existing out of the limelight after his career ended, and anyone having a conversation with him knew very quickly and in copious detail all the great things he'd achieved in tennis. People would see him coming and say, "Here comes the Grand Slammer." I promised myself that if I did manage to win the U.S. title, I'd never give anyone a reason to say that about me.

After I'd accounted for Rafael Osuna 6–1, 6–3, 6–4 in the semi, I readied myself to play the final against the man I knew in my heart was always going to be there to try to foil my Grand Slam: Roy Emerson. I could not help harking back to when Ken Rosewall deprived his great mate Lew Hoad of a Grand Slam at the United States titles, and wondered whether Emmo would do a Muscles on me. I knew that he'd be trying to.

The evening before the final, the Tennis Writers' Association of America staged a dinner to honour Sir Norman Brookes, one of Australia's finest players who in his career between 1898 and 1920 claimed all the major titles, a stalwart of our Davis Cup side and president of the LTAA from 1926–55. When he was presented with the Immortal Tennis Award for the lasting impact he had made on our sport, he spoke eloquently, and never more so than when he said he wanted an end to the amateur–professional divide so the world's best players in either camp could play against each other.

"I only hope I will be with you long enough to see an open championship," said Sir Norman. Happily, he was. He passed away on 28 September 1968, at age 90, exactly 20 days after the inaugural U.S. Open championship final. There were other awards doled out that night. Pancho Gonzales was given a Presidential Citation by the People-to-People Sports Committee for being the "Tennis Ambassador of the United States" and I won "World's Most Popular Tennis Player," which mystified me a bit because I was one of the more introverted blokes on the circuit.

Next day, against Roy Emerson, my strategy was to avoid my usual slow start and attack with my power game from the outset, to try to overwhelm Emmo and put him away in three sets because his superior fitness could be decisive if the match went to five. What was it Harry Hopman said? The fittest bloke will normally win the fifth set, so I wanted to end the match before then. In the first set I broke Roy's serve and won the first two games, always my objective in any match to get off to a good start and put pressure on my opponent, and claimed the first set 6–2. My service and drives were going exactly where I wanted them to, and this was instrumental in me winning the second set 6–4.

Then, as I knew he would, Roy rallied and began attacking me ferociously. I wilted under his accurate serves and volleys and made errors, and he won the set 7–5. His passing shots were always good and the grass court – Forest Hills was still grass in those days – was bouncy and suited him. I had to win the fourth. I just couldn't risk the match going to a fifth set, when I'd become a sitting duck for Roy. I took the ascendancy and unleashed every shot I knew and found myself leading 40-15 and serving for the match. There's no other way to account for what I did next. When I served and ran into the net to deal with Emmo's sitter of a forehand volley return, I had the wrong grip and I smashed Roy's return ... right into the net. Such setbacks have the potential to change the course of a match. I reined in my emotions, took stock, settled down, and thought of nothing but getting my first serve in. I did that, and Roy returned. I volleyed deep to his forehand. His passing shot went long down the line. I had won the match in four sets, 6-2, 6-4, 5-7, 6-4.

The Grand Slam was mine. In my jubilation I threw my racquet high into the air then ran with my arms outstretched to hug Emmo, who was waiting for me at the net with a big grin, as happy for me as he was no doubt disappointed for himself. As we walked off the court, Don Budge rushed over and shook my hand. "Welcome to the club!" he boomed, and I think he may even have meant it. He was certainly generous when he told reporters who invited him to compare us as players, "I'm glad I never had to play such a fine left-hander with all the shots. And I must praise Rod's and Roy's sportsmanship. I think some of our boys and other players could learn from them."

I was swamped by back-slappers and when reporters asked me how it felt to be the best player in the world, I told them I wouldn't know because there were guys named Hoad, Rosewall, Sedgman, Gonzales, Trabert and Segura whom I hadn't beaten, because I hadn't played them. I also knew that making up the 128 players in the major amateur tournaments were fellows who were not really up to standard, young blokes with a tennis racquet who travelled the world entering tournaments and rarely lasting a round.

There was no official dinner, no victory waltz, at Forest Hills. I was much happier to front up at the bar at the clubhouse there and shout anyone who wanted to have a drink with me. I know one bloke who'd earned his beer was Emmo.

Once more, the Australian media besieged Mum and Dad, and my mother offered one reporter the following gem: "Success hasn't changed Rod. He still calls me Mum." I don't know what else I could have called her.

I played in the Pacific Southwest tournament at the Los Angeles Tennis Club on my way home to Australia after the United States championships in New York. In the crowd and at the various functions were a number of celebrities who were serious tennis devotees, and seemed as much in awe of the players as we were of them. There were some big names I'd never thought I'd ever meet in my life, such as my childhood cowboy hero John Wayne, who shot up the open air picture show in Rocky where I was a front row regular, Charlton Heston, Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Lloyd Bridges, Dinah Shore ... These stars could handle a racquet and had courts in their backyards, and Kirk and Charlton invited me and some of the other players to their homes for Sunday tennis days and barbecues.

When reporters told me that a wax likeness of myself was being sculpted to stand beside Don Bradman's in the Sports Hall of Fame section of Madame Tussaud's wax museum in London, I turned bright red and ducked for cover. When I finally saw it, I had to admit the dummy wasn't a bad likeness ... they'd taken enormous trouble to get my facial features, legs and bulging left forearm right, and in the end I was proud to be included in such exalted company as Bradman, not to mention Madame Tussaud's galleries of kings, queens, emperors, movie actors, rock stars and serial killers.

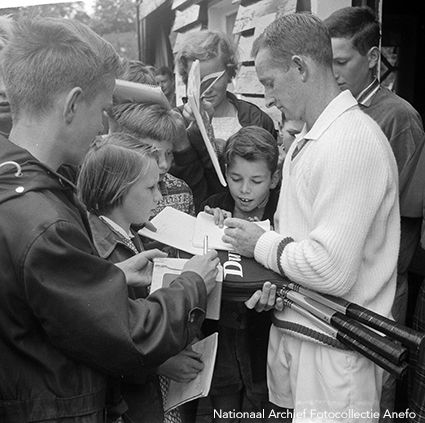

When I landed at Rockhampton airport on 27 September, I saw through the plane window a crowd of more than 1,000 people crammed five deep by the terminal. There were TV crews and photographers milling about. I wondered who they were there to see. When I disembarked, and there were Mum and Dad, my sister Lois and my brothers and friends, I realised they were there to see me. Amid all the hugs, kisses and back slaps, and cries of "Good on you, Rocket Rod!" and "Welcome home, digger!", Mayor Pilbeam, resplendent in his heavy chain, officially welcomed me home and presented me with a two-metre-long replica tennis racquet and the keys to the city. (Not that I've ever known what you're supposed to actually do with such keys!) When I was called upon to say a few words, I told the people of Rocky the truth, that I took strength from knowing that they were supporting me from afar, and this gave me confidence in big matches. I said that winning Wimbledon and the Australian title and representing Australia in the Davis Cup was a dream come true and every day I thanked my lucky stars. Claude Farmer, who had bought the Marlborough property from Dad, piped up and said if it wasn't for him I might still be out at Langdale ring-barking trees.

On the Saturday, there was a procession in my honour. I was plonked in a convertible sports car alongside Mayor Pilbeam and driven down East Street escorted by police on their motorbikes, the City Band and a tribe of local junior and senior tennis players in their whites holding their racquets high as we made our way to a civic reception at City Hall. Thousands of people lined East Street, cheering and clapping. I was truly overwhelmed. From there, I was whisked to the Criterion Hotel to be guest of honour at a luncheon hosted by the Central Queensland Tennis Association. You'd think I'd be better by now at public speaking, but my shyness took over and after mumbling a few words of thanks, I sat down with relief to a hearty meal. That night I was feted at the local speedway and did a lap of honour on the back of the motorbike of Queensland speedway champion Ivan Mauger. Days later I saddled up for the Queensland Hard Court Titles and beat Emmo in straight sets in the final, then teamed with him to down Wimbledon runners-up Fred Stolle and Bob Hewitt, who'd returned briefly from South Africa, in the doubles final.

By the time I returned to Australia, I had all but decided to turn professional as soon as the Davis Cup was done and dusted. Frank Sedgman and Ken Rosewall, who were acting on behalf of the IPTPA (Muscles was the secretary and treasurer), had made me a very good offer, upping the ante from what I'd been offered before the Grand Slam win. Still, I tossed and turned over my decision. One day I'd think becoming pro and guaranteeing my financial future was a no-brainer at my stage of life, and then I'd convince myself that I loved playing in those fabulous major tournaments at Roland Garros, Wimbledon and Forest Hills too much ever to say goodbye to all that. Money was definitely a factor making professionalism tempting, though. I wanted to secure my future, to be able to buy a home and perhaps settle down one day, make some investments. And my family wasn't flush with funds. Mum and Dad had helped all they could, buying my racquets, balls, shoes and clothes, and dropping everything and driving me to tournaments when I was a kid. Somehow, they made all that happen.

And these days I was always welcome to stay with them when I was touring in Queensland. They asked for nothing, and were perfectly happy with their life, their home and town, but I wanted to repay them by making them financially secure, perhaps buy them a better car. Whatever contortions I was going through in my head, publicly I didn't let on how I was feeling or give any indication of what I might do. I sounded out Frank and Ken, as well as Lew and Ashley Cooper, about what life would be like on the pro circuit, but the only people I told what was really in my heart were my parents and brothers, when I took some rest and recreation in Gladstone after returning from America and we talked long into the night about the importance of making the right decision.

I left Gladstone knowing I was going to turn pro. Having now achieved all there was to achieve in the amateurs it became obvious that I had to take on new challenges if I wasn't to stagnate. And didn't I owe it to myself and my family to profit from my talent? I'd been warned that it was inevitable that I would struggle at first on the professional circuit, every newcomer did, but if I ended up making it there was the chance to sock away a lot of money. That trip home to see the family, to fish and water-ski a bit with Bob and Trev, and to stay, as in the old days, with the Shepherd family for a week or two, cleared my head, brought me down to earth and put tennis, and life after tennis, in perspective.

I decided I wanted to play against the best players and also save some money. When I retired from tennis, I didn't want to be forced to put my name on someone else's sports store in Rocky, or trade in on my reputation by selling life insurance, or run a pub like many Australian champions in all sports ended up doing. LTAA president Norman Strange declared that he was resigned to losing me. "If Rod Laver turns professional, we wish him well. It is a personal decision Rod has to make, and we don't want to come into the picture. Rod has given Australia years of great service to amateur tennis and the LTAA is grateful. His loss would be regrettable but not tragic. There are many fine young players waiting to step into the Davis Cup squad. That is why Australia is the envy of the tennis world." It was comforting to hear Norman's conciliatory words. I had a feeling that Harry Hopman, an amateur to his bootstraps, might not be so understanding if I turned my back on the system that had made me and took the professional plunge.

-- Excerpted by permission from Rod Laver, An Autobiography by Rod Laver. Copyright (c) 2016. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.

Popular On ThePostGame:

-- Jim Palmer: How He Became Iconic Jockey Underwear Model

-- How Oakland A's Helped Launch 'Hammer Time' And Mrs. Fields Cookies Empire

-- Tommy Lasorda: How Dodger Icon Met Fidel Castro At Start Of Cuban Revolution