This week, Michigan hockey coach Gordon "Red" Berenson announced he was retiring after 33 years behind the bench. He leaves behind the greatest legacy in Michigan hockey's long and enviable tradition – but it all hinged on a couple lucky moments that changed the course of history.

Berenson loved the game from the start. When he was a 6-year old kid in Regina, Saskatchewan, for Christmas his parents gave him new skates, new gloves and new shin pads. He was so excited, he called his best friend – at 6 a.m.

When his friend's mom answered, she asked, "Do you know what time it is?"

Berenson replied, "Yes -- but this is important!"

Hockey has always been important to Berenson. And if you grew up in Regina, Saskatchewan, it probably would be to you, too. Regina, the provincial capital, is a tight circle of a city with no sprawl to speak of, which 180,000 farmers, politicians and businessmen call home. For more than a century, Regina's main businesses have been grain and government, neither of which is terribly thrilling to watch.

But if you're a hockey fan -- or better yet, a hockey player -- Regina's the place to be. The list of Saskatchewan natives who've played in the NHL runs 12 pages long, a remarkable feat for the only province west of the Maritimes that's never had an NHL franchise. The list includes Sid Abel, Ace Bailey, Johnny Bower, Glenn Hall, Eddie Shore, Bryan Trottier, Theo Fleury and a guy from a tiny town called Floral -- a town so small it's not even listed on the atlas index -- named Gordie Howe.

Berenson and his friends would skate outdoors on Regina's natural rinks and ponds all day, and go home for dinner with their skates on so they could rush back out to play some more as soon as they were excused from the table. When the snow drifted up to the top of the boards they shoveled it off, and when the 40 mile-per-hour winds rushed across the plains from Alaska, they leaned hard into it and kept skating. "Some days," Berenson recalls, "skating into that wind felt like you were going up hill."

While he was still in high school, the Montreal Canadiens invited him to turn pro as soon as he graduated, but the staunchly independent Berenson decided to conduct a thorough investigation of U.S. colleges. In the spring of 12th grade, he and his hockey buddies trotted down to the only library in town to search for the school that had the best combination of academics and hockey. Berenson knew the college for him when he saw it.

"It was pretty clear Michigan stood at the top," he says. "After I came down on a visit, I came back and told the other guys, 'This is where we're going.'"

And just like that, a pipeline of 14 blue-chip hockey players started running from Regina to Ann Arbor.

Berenson's decision came with a price. Frank Selke, the Montreal GM who had drafted Berenson -- and in whose name the NHL gives the annual award for the best defensive forward -- warned him, "If you go to an American college, you'll never become a pro."

Fully aware he might be sacrificing the dream of every Canadian boy to play in the NHL -- and for the Montreal Canadiens, no less -- Berenson didn't flinch. After sitting out the two semesters the NCAA required then, and playing one semester for the Canadian national team, Berenson suited up for his first game on February 5, 1960, against Minnesota.

"Ninety seconds into his first game he takes it all the way down the ice and scores," his former coach Al Renfrew told me. "Mariucci says, 'Man, at this rate we're going to lose, 60-0!'"

Almost. Berenson assisted on another five minutes later and scored a third later in the game. They had seen the future of Michigan hockey, and it looked bright indeed.

He scored 43 his senior year, in just 28 games. That's still a Michigan record, even though they usually play ten more games now. Berenson was simply the best player Michigan has ever produced.

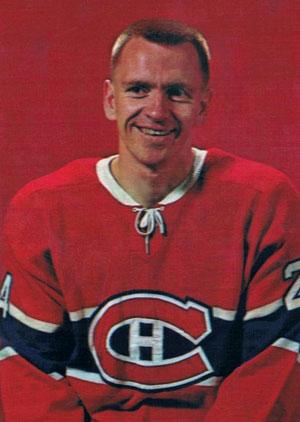

His senior year ended in disappointment when Clarkson upset Michigan in the 1962 NCAA semifinals. Minutes after Michigan won the consolation game Saturday night, Berenson got a ride to play the next night for the Montreal Canadiens. With that game, he became the first college player to go straight to the NHL -- and proved Frank Selke wrong. Berenson also became the first NHL player to wear a helmet who hadn't already suffered a head injury.

Three years later, Berenson's Canadiens played the Chicago Black Hawks in the 1965 Stanley Cup Final. One day Berenson was holding Bobby Hull's line in check in the seventh game to win the grail, the next day he was sitting in Michigan business school classroom starting on his M.B.A. (There is drama in Berenson's final games.)

Although his B-school classmates didn't know who he was, Berenson remembers "very clearly what a good feeling it was to be there. I was preparing for life after hockey."

But his NHL career lasted 17 years. "I always thought about what I'd do when it was over, but for one reason or another, it hasn't ended," he says. "I was lucky. With expansion and the WHA, I played until I was 38."

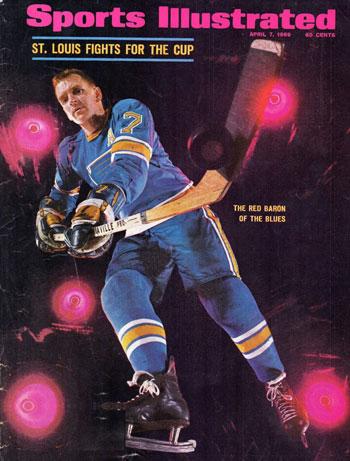

Along the way, he was named to six All-Star teams, played in the famous 1972 Summit Series, served as an assistant captain in Detroit and the captain in St. Louis, and once score six goals in one game, still an NHL record for a visiting player.

One year after Berenson hung up his skates in 1978, St. Louis named him head coach. In 1980-81, his first full season, he was named NHL Coach of the Year. The next season he was fired, which shows you what the NHL is all about.

Michigan athletic director Don Canham had tried to recruit Berenson to take over his alma mater's team twice before, but both times Berenson was under contract to NHL teams. When the Berensons brought their oldest son, Gordie Jr., to Ann Arbor in the spring of 1984 on a campus visit, Canham got word that the Red Baron was on campus, and hurriedly invited him down to his office to offer him the head coaching job once more. The third time was the charm. Berenson took it.

"Red was brought in to save the program," said former PR man Jim Schneider. "If he didn't, it was gone."

That might be an overstatement, but not by much. The once-proud Michigan program found itself on the bottom of an upstart league, the CCHA. The situation was undeniably dire.

"I never saw myself as a college coach -- but then I never saw myself as a coach," Berenson says. But there he was, the fourth Michigan captain to be named coach, standing up at his first press conference to tell people how he intended to restore the emaciated program to its former robust health. "My first goal is to change the image of the program," he said. "I have a good feel for Michigan, the tradition, the excellence, and what I call a 'Michigan kid.'"

He rebuilt it, but he did it the right way, which takes longer. He honored the scholarships of the players he'd inherited. He followed the NCAA's countless rules – even the stupid ones – and he graduated his players.

Six years later, Michigan finally returned to the NCAA tournament – and kept it up for 22 straight years, an NCAA record. Under Berenson, Michigan won 20 CCHA league titles, went to 11 Frozen Fours, and won the NCAA title in 1996 and 1998. Perhaps most impressive: Four players from those national title teams would graduate from Michigan's medical school.

That is how you do it.

And that's why his players will tell you Berenson was invariably more proud of what they did off the ice than on it. Perhaps that explains why his players maintained a 90-percent graduation rate, until they started jumping early to the NHL – a victim of his own success.

Berenson knew what Michigan stood for, and he recruited players who understood that by turning the tables on them. Instead of telling them all the great things Michigan was going to do for them, he looked them straight in the eye and asked what they could do for Michigan.

Fifty-two years after Berenson started preparing for life after hockey, he will actually start his life after hockey, at age 77.

Nobody needs to ask what Berenson did for the game of college hockey, or Michigan in particular. The answer is simple: He did everything he could.

John U. Bacon is the author of four New York Times bestsellers. His latest book, Endzone: The Rise, Fall and Return of Michigan Football, is now available in paperback with an update covering the 2015 season and 2016 off-season. He gives weekly commentary on Michigan Radio, teaches at the University of Michigan and Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism, and speaks nationwide on leadership and diversity. Learn more at JohnUBacon.com, and follow him on Twitter @johnubacon.