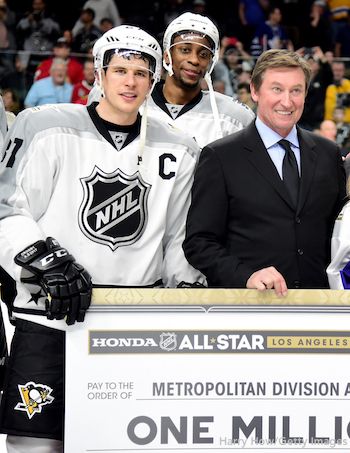

Wayne Simmonds capped a memorable NHL All-Star weekend in Los Angeles by becoming just the second black player to win the game's MVP award. For a league that has been needled for being so white for so long, this was a significant moment, an opportunity to spotlight its growing diversity at the same time it honored the 100 greatest players of all time as part of the NHL centennial celebration.

Just 10 miles southwest of this rollicking puck extravaganza, which had transformed downtown L.A. into Hockeywood, thousands marched outside terminals at LAX airport to protest the president's travel ban on those from seven predominantly Muslim countries. Sports can be a wonderful diversion, but it doesn't doesn't exist in a vacuum. As traffic thickened the closer you got to LAX and helicopters circled, it was impossible to ignore this confluence of fun and games with the grim reality that people were being detained at this airport and others, and in one case at Washington's Dulles International, a 5-year-old boy was separated from his mom.

Writers sometimes fall into the trap of forcing a storyline to align with a broader narrative, so it is a dicey proposition then to try connecting dots between a hockey exhibition and a pivotal moment in the history of the nation beyond the geographic proximity of what unfolded Sunday afternoon in Los Angeles.

But sports has shown that contact, connection and interaction can lead to understanding, empathy and inclusion, and that is a message any decent-minded person should appreciate, regardless of specific political persuasions, particularly in moments as volatile as the present. This is in no way an attempt to equate the magnitude of hockey with the travel decree, but the NHL All-Star festivities did illustrate how, within the league's own sphere, two of these storylines played out.

The NHL had been an easy punchline historically for its lack of black players. That was more a product of demographics than intentional exclusion, but the NHL has been aggressive the past three decades in its efforts to make the game accessible to more people from both a fan and participatory perspective. Simmonds was among four black players competing in this All-Star Game, another sign of progress.

The league, though, has never received enough credit for its international diversity. None of the countries included in the ban has a direct bearing on the NHL. Yet as a league that thrives on the contributions of stars from various nations, the effect and intent of the ban should resonate deeply. Will my country be next?

For some context, let's look at 1986, the year that Grant Fuhr was the first black player to be MVP at the NHL All-Star Game. If the league had wanted to select its 100 greatest players at that time, the list would've been nearly all Canadians. No Russians, no Czechs, no Finns, no Americans. Maybe one Swede with Borje Salming. Now such players are commonplace on rosters throughout the NHL, the captain of the L.A. Kings is from Slovenia and the first overall pick in last year's draft is from Scottsdale, Arizona. The game of hockey is better because of all this.

More than any other sport, hockey can be seen through the prism of the Cold War when distrust and division reigned. Consider Igor Larionov and Slava Fetisov. They were two of the Soviet players that faced the U.S. in the Miracle On Ice game at the 1980 Olympics and thus were viewed as the hated enemy. Then in the late 90s, they heard deafening cheers from American fans for helping the Detroit Red Wings win Stanley Cups.

In 1987 the NHL scrapped what had been its traditional conference-vs.-conference format in the All-Star Game to host Rendez-vous, a two-game series in Quebec City between its top players and the Soviet national team. The event grew beyond hockey to become a larger cultural exchange, and six months later, when the Soviets returned to compete in the Canada Cup, Wayne Gretzky arranged a dinner at his house where he served steaks and Molsons to a small group including Larionov and Fetisov. The Soviet Union was in the process of crumbling on its own, but this meeting with Gretzky might have accelerated the plans for these players to try joining the NHL. Long before George W. Bush coined the phrase, the Great One had walked the walk of being a uniter, not a divider.

When the NHL 100 was revealed Friday, the list included Russians like Alexander Ovechkin, and Czechs like Jaromir Jagr, who has always worn No. 68 as a tribute to the Prague Spring revolution of 1968, another reminder of how sports can be a platform for bigger issues.

The president's travel ban triggered a massive outcry globally, including athletes and coaches -- and the reporters who cover them. This led to some backlash with the hashtag #StickToSports gaining enough traction that it prompted Bryan Curtis of The Ringer to write a column about how the era of "stick to sports" is over.

Maybe that is for the best because sports isn't detached from the rest of society.

As Barack Obama said when the Cubs visited the White House in mid-January, "It is a game and it is celebration, but there's a direct line between Jackie Robinson and me standing here."

And as Red Smith, the iconic sports columnist who won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary, put it: "Any sportswriter who thinks the world is no bigger than the outfield fence is not only a bad citizen, but also a lousy sportswriter."

So call me bad, call me lousy, but it won't be because of passing on the chance to offer some perspective to the surreal weekend I just experienced in L.A.