Excerpted from INDENTURED: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA by Joe Nocera and Ben Strauss with permission of Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 Joe Nocera and Ben Strauss.

Sonny Vaccaro's favorite movie is The Insider, starring Russell Crowe and Al Pacino. The 1999 film tells the story of a former cigarette executive named Jeffrey Wigand, played by Crowe, who gains possession of hundreds of damning internal documents and becomes the first whistleblower from inside the tobacco industry. Pacino plays Lowell Bergman, a renowned television producer who relentlessly pursues and cultivates Wigand as a source as he prepares an expose of Big Tobacco for 60 Minutes, the CBS newsmagazine show.

"I must have seen the movie three or four times," Vaccaro says. "I was mesmerized by it. It inspired me."

By 2010, Bergman was gone from 60 Minutes and had moved to Frontline, the PBS weekly documentary show, where he was an on-air interviewer as well as a behind-the-scenes producer. He had also joined the faculty of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, where he organized a conference on investigative reporting every spring.

Vaccaro was by then some four years into his crusade against the NCAA. He'd had one important early success, helping to convince Michael Hausfeld to file the Ed O'Bannon lawsuit. But that litigation would surely take years to get to trial, assuming it wasn't settled first. From time to time, Vaccaro would get invited to make a speech on a college campus, and while he was getting larger crowds than he had at the beginning, his talks were not making much of an impact on the wider world. Not long after he left Reebok, he had lunch with James Gandolfini, the star of The Sopranos, who was considering playing him in an HBO film. That would certainly put his cause on the map, but while Gandolfini agreed to play the part, the film was still years away. When Gandolfini died suddenly of a heart attack in the summer of 2013 at the age of fifty-one, the movie still hadn't been made.

Then, in the spring of 2010, during one of his occasional forays to New York, Vaccaro had lunch with Armen Keteyian, an investigative reporter for CBS who specialized in sports stories and had done work over the years for 60 Minutes. Vaccaro asked Keteyian if he knew Lowell Bergman; Keteyian said he not only knew him, he would soon be heading to Berkeley to attend Bergman's conference. "Can you make contact with him for me?" Vaccaro asked. Keteyian came back from Berkeley with permission to give Vaccaro Bergman's e-mail address.

In June, Vaccaro e-mailed Bergman, requesting a meeting. He responded by asking Vaccaro to send him "something in writing" that would give some details about what he wanted to talk about. ("Saves a tremendous amount of time.") Vaccaro ignored Bergman's request, and instead sent Bergman a second e-mail: "Currently I am involved with the O'Bannon lawsuit as an unpaid advisor," he began. "It is this case and many other things I have witnessed over the years in sports at the highest corporate levels that are inconsistent with the ideals of amateurism in America on the collegiate level. I would like to meet with you not necessarily with a specific agenda but to discuss thoughts I have had over the years pertaining to the mix of amateurism and professionalism and to share my thoughts with you on the moral and ethical solutions."

He continued, "I know what you have done and who you are and what you stand for. Over the past four years I have been following a different path in my continuing fight against what is called today amateur athletics." Intrigued, Bergman set up a meeting for later that month. On the appointed day, Vaccaro and Pam made the two-and-a-half-hour drive from Carmel, where they were then living, to Berkeley -- only to be told that Bergman didn't have a lot of time, twenty minutes at the most. Instead, they spoke for two hours.

It didn't take Bergman long to realize why Vaccaro hadn’t tried to put his thoughts down on paper. That approach would never work with Sonny Vaccaro; he neither spoke nor thought in a linear fashion. No matter. What Vaccaro told Bergman shocked him -- just as it had Hausfeld and Jon King. “This guy is telling me that athletes only get one-year scholarships, so coaches can cut them. He's telling me about all the money being made in college sports and the athletes aren’t getting any of it. He’s telling me that they don't get workers' comp if they get injured, and that the NCAA gets around that by calling them ‘student-athletes,’” says Bergman. "I was dumbfounded."

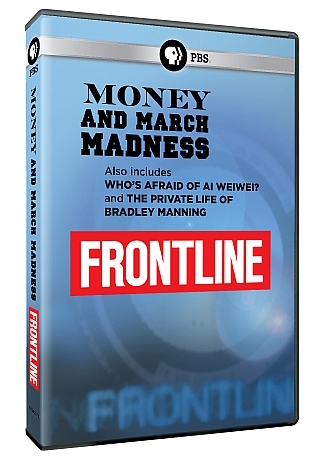

Largely on the basis of that meeting, Bergman decided to do something about the NCAA for Frontline. The story didn't run until March 2011 -- timed, naturally enough, to air just as the NCAA's March Madness tournament was getting under way. Titled “Money and March Madness,” it was only twenty-one minutes long. But it covered all the bases -- bases that were all too familiar to people like Andy Schwarz and Ramogi Huma, but were a revelation to the millions of people, even dedicated sports fans, who didn’t follow the ins and outs of the NCAA.

On camera, Andrew Zimbalist, a Smith College sports economist and author of Unpaid Professionals, his stinging critique of the NCAA, explained to Bergman the unfairness of the one-year scholarship. Best-selling author Michael Lewis, who had written The Blind Side, about an offensive lineman at Mississippi, described college athletes as “indentured servants,” echoing Schwarz and Jason Belzer. O’Bannon told Bergman about his lawsuit, while Vaccaro, in his usual excitable fashion, explained that he had left Reebok to "go after the complete fraud of amateurism in America."

Vaccaro had persuaded Chicago Bulls star Joakim Noah, who had played at the University of Florida, to speak to Bergman. “There is a whole lot of exploitation going on,” said Noah, who told him about the sense athletes had that the NCAA’s real mission was to nail them for something. (“Oh, this kid’s dirty,” he said, recalling things players would hear.) Noah had loved playing college basketball, he said, and he loved his coach, Billy Donovan, whom he was still close to. “Kids giving everything they’ve got, and doing it for their schools -- that’s a beautiful thing,” he said. "But who are these people making all this money, and shouldn’t the kids get a piece of it?"

Watching "Money and March Madness,” one gets the sense that the NCAA never saw it coming. And why would it have? March Madness usually brought it glowing press. The worst criticism the NCAA got in the non‑sports press was that the graduation rates were low -- something that Mark Emmert claimed to be addressing with the new ban on postseason play for schools that didn’t score above a certain number in their academic progress rate.

Emmert himself went on camera to defend his institution. He came across the way corporate spokesmen often do when confronted by a tough television interviewer: defensive, cautious, wedded to his talking points -- and a little shell-shocked at the questions he was being asked. No doubt, he expected Bergman to ask him about the NCAA’s $10.8 billion contract with CBS and Turner Broadcasting to televise the tournament. But he seemed surprised when Bergman asked him about his own salary, which he refused to divulge. (Instead, Bergman noted that Brand had been making $1.7 million when he died.) He bridled when Bergman asked his response to Michael Lewis’s contention that the way college sports treated its athletes was unjust. He seemed taken aback when Bergman handed him the document that athletes had to sign in order to play -- and asked whether this was why they didn’t control the rights to their own images. When Bergman asked him why the NCAA wouldn’t use some of its riches to fly players’ parents to the Final Four -- something Noah had complained about, noting that many parents couldn’t afford the trip -- Emmert huffed, “The NCAA doesn’t provide travel benefits for families.” Over and over, he kept insisting that “student-athletes are students, not employees.” Maybe in a friendlier forum this answer might have sufficed. But on Frontline, it sounded hollow.

Vaccaro contends that Bergman’s story was important not just because of its content but also because of its audience. A journalist completely outside the realm of sports, working for a media organization that was aimed at an elite, educated, nonsports audience, had looked closely at the NCAA and found it wanting. Issues of due process, injustice, and exploitation would resonate with this audience. Just a few years before, the White case had gotten almost no publicity. Yet the O’Bannon lawsuit was now getting exposure on PBS. “Things really started to feel different,” says Vaccaro.

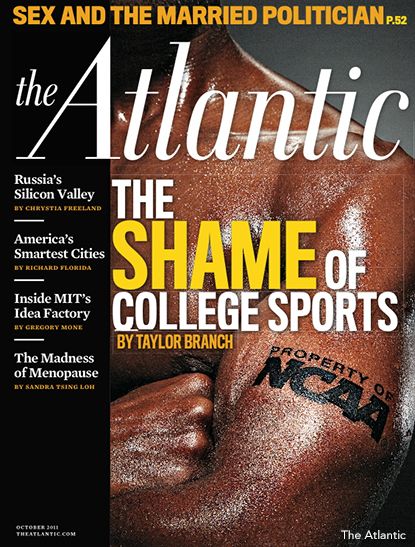

If Bergman was one of the first important nonsports journalists to delve into the inequities of the NCAA, a second one was right behind him. Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer Prize–winning historian best known for his three-volume history of the civil rights movement, had accepted an assignment from the Atlantic magazine to examine the NCAA. Branch knew a lot about sports, which was why the NCAA intrigued him; he had been a football star in high school, and had also coauthored Bill Russell’s fine autobiography, Second Wind. One of the first people Branch sought out was William Friday, the cofounder of the Knight Commission, who had spent some thirty years as the president of the University of North Carolina system; the two men had known each other since the days when Branch was a student at Carolina. A passionate believer in amateurism, Friday “positively exhorted me to take on The Atlantic project and rescue colleges from the NCAA’s money trap,” Branch later recalled in an e-mail. “His charge was literally to 'give the university back to Socrates,' which I took to mean restoring the primacy of academics.” That was Branch’s starting point.

As he worked on the story, however, “the scales fell from my eyes,” and by the time the article came out in the October 2011 issue of the magazine, Branch had arrived at a very different place. The cover image showed the sweaty torso of a muscular African American athlete with a tattoo on his arm that read “Property of NCAA.” The story was titled "The Shame of College Sports."

The real scandal in college sports, Branch wrote, “is not that students are getting illegally paid or recruited, it’s that two of the noble principles on which the NCAA justifies its existence -- ‘amateurism’ and the ‘student-athlete’ -- are cynical hoaxes, legalistic confections propagated by the universities so they can exploit the skills and fame of young athletes. The tragedy at the heart of college sports is not that some college athletes are getting paid, but that more of them are not.” In an online video accompanying the article, Branch said, "There is absolutely no justification, in principle or law or reason, why the people who are generating all of this money, these hundreds of millions of dollars, shouldn’t be entitled to a piece of it."

Branch was struck by the way the NCAA punished athletes for selling their university-branded football paraphernalia for tattoos (there was just such a case with a handful of Ohio State players in 2010), yet these same football players wore corporate logos of companies that were paying millions for the privilege. "Last season, while the NCAA investigated him and his father for the recruiting fees they'd allegedly sought," he wrote, "Cam Newton compliantly wore at least 15 corporate logos -- one on his jersey, four on his helmet visor, one on each wristband, one on his pants, six on his shoes, and one on the headband he wears under his helmet -- as part of Auburn’s $10.6 million deal with Under Armour."

It also did not escape Branch’s notice that the majority of athletes who played college football and men’s basketball were African American. “Look at the money we make off predominately poor black kids,” Dale Brown, the former basketball coach at Louisiana State University, told him. “We are the whoremasters.” In the most incendiary line in his article, Branch wrote that the NCAA lets off "the unmistakable whiff of the plantation."

Walter Byers had used that same word in his 1995 autobiography, but the country hadn’t been ready to hear it. Now it was. In the months after his article came out, Branch was the country’s most visible NCAA critic. He was invited onto television shows and college campuses to detail his critique. His article was tweeted and talked about. Inside the NCAA, executives passed it around like samizdat. If Bergman’s Frontline story had caused tremors, “The Shame of College Sports” was more akin to an earthquake.

As the earth began shifting under the NCAA, Emmert and his staff seemed completely unprepared to deal with the new tougher scrutiny they were facing -- scrutiny that was suddenly coming not just from one-off magazine articles, but from the community of sportswriters who covered the NCAA, most of whom had always before accepted its version of reality. Sportswriters like Dennis Dodd at CBSSports.com, Andy Staples of Sports Illustrated, and the blogger Patrick Hruby became relentless critics of the NCAA. Longtime NCAA practices -- practices that had rarely been the subject of press coverage, much less criticism -- were now being held up to ridicule: the Harvard freshman women’s basketball player who lost a year of eligibility because the NCAA misunderstood the significance of a standardized test she had taken while living in England. The graduate student with a year of eligibility left who went to a different graduate school and couldn’t play because the NCAA refused to grant him a waiver from the rules that transfers had to sit out a year. The two years’ probation meted out by the NCAA to the University of Nebraska because the athletic department had violated a rule covering, if you can believe this, textbooks. Nebraska had mistakenly covered the cost of athletes' books that their professors recommended for their classes rather than only the ones their professors required, which was what the NCAA allowed.

The deference the sports press used to accord the NCAA was replaced by withering commentary. Pat Forde at Yahoo.com started using the phrase “College Sports, Inc.” whenever he wrote about commercialism. Staples’s articles, often dripping with sarcasm, stressed the NCAA’s inconsistent application of its rules, many of which he clearly found to be idiotic. (“Welcome to the maddening world of the transfer athlete at the mercy of the NCAA, where the rules apply as written -- unless they don’t,” he wrote in one of his stories.) Dodd went straight at Emmert himself, even calling for him to resign in February 2013.

Writers who had never before thought to take on the NCAA began to see the sports beat differently. One such journalist was Jon Solomon, a college football writer for a relatively small newspaper, the Birmingham News in Alabama (he has since moved to CBSSports.com). In 2011, he wrote a six-part series examining how college athletes were treated, a series that flowed from one central idea: “There was a lot of new money flowing into college sports,” he says, “and the paper wanted to know what the athletes thought about it. Who was speaking for them?” He wrote stories about health insurance for college athletes, Ramogi Huma’s efforts to build an organization that would advocate for players, and the NCAA’s commercialism committee. When he learned that a former Duke basketball star named Jay Williams had once authored a paper documenting how the Duke jersey with his number 22 had generated more than $1 million in sales for apparel companies and Duke, Solomon wrote about that too. By 2013, he was writing almost exclusively about the NCAA, with an emphasis on the O’Bannon case and other NCAA-related litigation, about which he was one of the acknowledged experts among the press corps.

Sportswriters were not the only ones piling on. Coaches used to live in fear of the NCAA, yet in December 2012, John Calipari, the controversial Kentucky basketball coach known for recruiting "one and done" freshmen -- players who leave for the NBA after a single season in college -- felt emboldened enough to write a blog post harshly critical of the NCAA for its rules about food. Athletes were only allowed to eat university‑provided food the three times a day they were at the training table -- and couldn’t even bring snacks from the training table to their rooms. “We’re signing billion-dollar agreements and moving teams across the country for money, and we’re worried about a kid eating a sandwich at night,” he wrote. (Calipari later wrote a book in which he described the NCAA as a crumbling empire, comparing it to the Soviet Union just before the Berlin Wall fell.)

At USA Today, a reporter named Steve Berkowitz created a database of coaches' salaries and athletic department revenue, which became a much- covered annual event. Brad Wolverton of the Chronicle of Higher Education began to write deeply reported stories that burrowed far inside university athletic departments. One of his most memorable articles, published in the summer of 2012, was about the culture of academic counseling, which had grown enormously since the NCAA stopped requiring minimum SAT scores in 2003. Wolverton built his story around a University of Memphis football player named Dasmine Cathey, who could barely read when he got to college, struggled academically throughout his four years, and, despite badgering from the academic support staff, remained several courses short of graduating by the time his eligibility was up. He was working as a deliveryman.

No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. INDENTURED is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Joe Nocera on Twitter @NoceraNYT. Follow Ben Strauss on Twitter @benjstrauss.