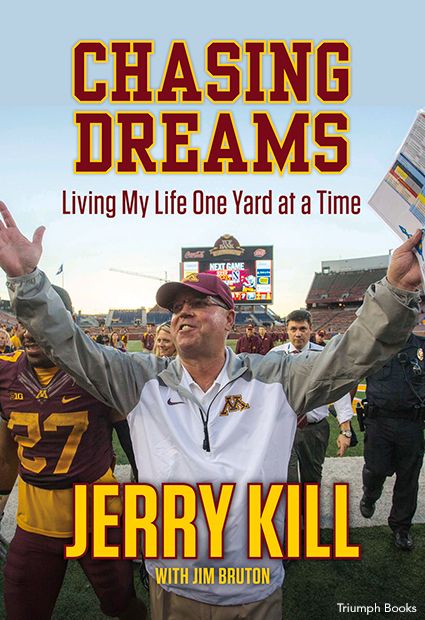

In Chasing Dreams: Living My Life One Yard at a Time, legendary football coach Jerry Kill, with the help of co-author Jim Bruton, explains how he has managed to fulfill all of the responsibilities of his position throughout his career. By always putting the players first, he's maintained a reputation for being more than just a coach who wins, but one who leads, teaches and cares. Kill's coaching career spans more than three decades, and in that time he touched countless lives up until his sudden retirement in October 2015 due to health issues related to epilepsy, a condition that had caused four seizures on the sidelines during games.

When I was offered the job at Minnesota, we never had any family discussions about whether I shouldn't take the job because of the epilepsy. We never discussed the bigger stage, the more stress that might be involved, or anything like that. It seemed like a great opportunity to go to the Big Ten conference, and we took it.

My health issues, including the seizures in the beginning, were more of an annoyance than anything else. They kept me off the field, and I didn't like it. Still, after all I had gone through to that point and over the coming years, I only missed one football game. My mind was on football, not something I didn't even understand.

Before Minnesota, we never spent any time trying to find out what was going on with me. For me, my take on it was a "seizure disorder." I never called what I had epilepsy. I said it must be a seizure disorder from fatigue.

I had a couple doctors tell me a few things about what I had, in St. Louis and again at Northwestern, but to be honest, I never paid any attention to what they said. I didn't have time for all that. I mean, if no one else in the medical profession could really understand and explain the whats and whys, how was I supposed to get it?

For me it was simple. As I mentioned, I figured I overworked myself, never got much sleep, my body would get tired and run down, and I would have a seizure. It was more of a mental thing in my brain -- at least that was my take on it.

There are some among my family and friends who did feel that my workload would be greater. I never felt that way. I was always up for any challenge. At Southern Illinois, I collapsed on the field, and at Northern Illinois I had the seizures but not as publicly. But how would it be at Minnesota, where I was more in the spotlight with the massive media market in the Twin Cities?

When I had my first seizure there -- at least that people knew about -- my first year at Minnesota, it got a lot of attention. And there was a woman -- Vicki Kopplin, the head of the Epilepsy Foundation in Minnesota -- who wanted to get to me and talk to me.

She wanted me to get involved with the Epilepsy Foundation and be kind of a figurehead for the organization, that kind of thing. Initially I thought, I'm not doing that. I will lose my job. If people know all about my history, it won't be good.

Well, Vicki didn't give up. She kept at me. I mean, she kept trying to get an appointment to see me for about two years. She had been very persistent, and finally I agreed to talk with her. I gave her 15 minutes. She was telling me about this gala that was coming up and how I could help all these people. She went on about how I could be a great ambassador for epilepsy, and she was very persuasive.

Finally I said, "Okay, I'll go to the gala." So I went to the gala to help them raise money. At the event they had adults and kids speak about epilepsy and things they had gone through, and I thought, Wow, this is something to hear all these people. I thought, How good do I have it? What I heard about some of the kids was just terrible. With their problems, their future was so bleak. It really hit me hard. I felt so bad for some of the people who were there.

I spoke at the event and I told Vicki I would help her, and we became a team. It wasn't long before people were reaching out to me for advice. I met a lady named Deb Hadley whose daughter had died of epilepsy. And she wanted to get it out there that people were dying from this disease. I met her after her daughter died, and she just wanted to talk to someone. I was there for her and was really moved by her experience.

This was kind of how it all began with the Coach Kill Chasing Dreams Epilepsy Fund. I give Vicki all the credit. There is another person named Mark Evenstad, a great donor, who was in influential in getting our fund going.

Rebecca was instrumental in starting the Go-Pher Epilepsy Awareness Game at TCF Bank Stadium -- a game that strives to bring awareness to epilepsy -- and it really got things rolling for the foundation. Eventually, down the road a ways, this connection ended up saving my life.

At Minnesota, there was no question I was on the big stage. Everything I did was evaluated and scrutinized. It has been my practice that I never personally follow what the media says or writes. I don't read it and I don't watch it. But I do have someone who checks it for me, mostly to be sure if I am quoted, it is the right quote. The reason I stay away from it is that I feel the media has the right to say what they want to say. And I was told a long time ago that if you are going to worry about what everyone says about you, it isn't going to help you. As a coach, it seems best to put yourself in a bubble and worry about your football team and nothing else. If you don't read or listen to the media, what you don't know isn't going to hurt you.

Probably the only exception for me is things written by Sid Hartman of the Star Tribune. Sid has been around so long, and we have such a good relationship, that I totally trust him. Sid might stop by with an article he wants me to read, and I'll do it because it's Sid asking or giving me something to read.

There was one writer who did get to me some with something he wrote. It was an article by Jim Souhan of the Minneapolis Star Tribune that ran on September 15, 2013. Souhan said some pretty nasty things about me without any personal knowledge of what I was going through at the time. (Since the article, Rebecca and I have made amends with Jim and moved on.)

The article came after the Western Illinois game, when I had a seizure on the sideline. It was a Tuesday, and I was back at work getting ready for practice. I had put my practice clothes on and walked out, and there was no one in the office or anywhere around. Something was going on, but I didn't know what. So I went to the player' lounge and saw some people there watching something on the television.

The program was Outside the Lines, and they were talking about me and a sportswriter from Minnesota. I couldn't figure out what was going on. Why were they talking about me on that program? ere were some national gures talking about Jim Souhan and blasting him, and I thought, What the hell am I doing on Outside the Lines, and what does this have to do with Souhan?

Someone then told me there was an article in the paper that Souhan had written about me. When practice was over, Jim came over to me and said he wanted my reaction to his article. He never really apologized, and I told him, "Jim, you can write whatever you want and say what you want. I can't do anything about that. If there comes a time when I feel I can't coach the game, then I'll walk away." Well, I hadn't read the article yet.

When I got home that night, I said to Rebecca, "What do you know about this article by Jim Souhan?" And she said, "You don't want to read it." I told her, "Well, Jim Souhan came up to me after practice and kind of wanted to talk about it." So I then read the article, and my first reaction was, "You've got to be kidding me! He has no idea what I've been through."

The article basically said I was an embarrassment to the university and no one should have to watch someone "flipping around on the ground." I mean, it was brutal. I recall saying, "Man, he has offended every disabled person in America." And that’s when the fireworks started. I never talked to him after that, until recently.

After the article, I got letters, and people contacted me from all over the country. It was absolutely unbelievable the people who reached out to me because of the article. I had so much support from people. There were people who privately told me they had epilepsy but had not revealed it to anyone out of fear of losing their jobs and friends.

I was angry and also offended for all the other people who Souhan had attacked with his article. My reaction was not good, I admit that, but I didn't let it eat at me. I mean, what was I going to do?

As I look back, Souhan's article did more for epilepsy than a hundred good articles. He brought more awareness to epilepsy than could ever have been imagined. There is no doubt that because I was on a big stage, it got so much more attention. If I had been a normal person, little likely would have been said after the fact. Because I was a major college football coach, the attention to the article was so much greater, and the effect it had on people was unbelievable.

-- Excerpted by permission from Chasing Dreams: Living My Life One Yard at a Time by Jerry Kill With Jim Bruton. Copyright (c) 2016. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.