Nicholas Horbaczewski is a grown man. He has two degrees from Harvard.

And he really said this:

"What would real life Mario Kart be if you were flying through the air at 80 miles per hour? That's where we're going."

Horbaczewski is CEO of the Drone Racing League, which launched Jan. 25 in the basement theater of Brooklyn's Wythe Hotel. The brick hipster building stands in the midst of graffiti-lined streets. Manhattan skyscrapers rise on the opposite side of the East River.

The setting was fitting for the Drone Racing League's debut. On the outside, a professional racing league for unmanned air vehicles sounds alternative. On the inside, like the Wythe Hotel's basement, which features a modern bar and a 70-seat theater, the Drone Racing League has the feel of a mainstream product.

"You see a lot of the coverage of drone racing saying, 'Is this the sport of the future?'" Horbaczewski says. "If that's the article you're writing after watching it, it's not compelling. No one goes to a Broncos-Patriots game and writes, 'Is football really entertaining?'"

Ironically, DRL's first YouTube video is titled "The Sport of the Future." But the DRL says it is focused on enticing fans right now.

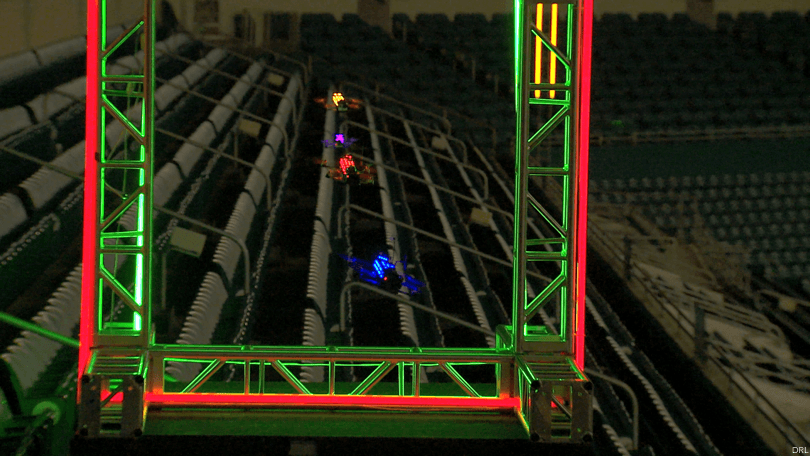

Drone racing is what it sounds like -- and more. Three-dimensional robots fly as fast and as precisely as possible from a start line to a finish line. Venues are three-dimensional and expand beyond the pilot's field of vision. Pilots use VR goggles to get a POV video feed from a camera in the cockpit of the drone, and they dictate the vehicle's movements with a remote control.

"A lot of it we can't talk about because we patented the heck out of it," Ryan Gury, DRL director of product, says to the launch party crowd.

DRL's first test came in a "preseason" race at a venue called "Gates of Hell." Horbaczewski and his staff turned an abandoned power station in Yonkers, New York, into a 3D venue.

From there, DRL turned to Sun Life Stadium, home of the Miami Dolphins. Real estate developer Stephen Ross, owner of the NFL franchise and stadium, invested $1 million into DRL through his RSE Ventures. DRL's official opening race at Sun Life Stadium will go live on the Internet Monday.

"We always say drone racing is basically a real-life video," Horbaczewski says. "If you think about racing games growing up, and you take all those things, and you layer it on, and you think about all the things that can make it interactive, you can do a lot of with it.

"We're not just trying to create a new sport. We're trying to create a whole new form of entertainment that blurs that line between the digital and the real and makes a real life video game."

Drone racing has gained steam the past decade as the unmanned vehicles have gone mainstream. Horbaczewski saw the sport for the first time in February 2015, one month after leaving his position as senior vice president of revenue and business development for Tough Mudder. By April, he went "all in." Investors such as RSE Ventures, CAA Ventures, Hearst Ventures, Strauss Zelnick (CEO of Take-Two Interactive Software) and Matthew Bellamy (lead singer of Muse) filed in.

By mid-December, Horbaczewski was ready to go with a TV-caliber video crew in Miami. DRL filmed its first race shortly after Monday Night Football, using ESPN equipment already in place. By January, the league was officially underway.

From a business standpoint, there are a number of holes, and Horbaczewski admits decisions will need to be made on the fly. For the time being, DRL races are filmed live, but edited and published afterwards. On-site attendees are VIPs. The majority of the public will see the races recorded on digital platforms (YouTube, TheDroneRacingLeague.com).

"There's a traditional sports league model, which is sponsorship, media rights, licensing," Horbaczewski says. "That's how pro teams make their money. No one could ever show up to an NFL game again and the NFL would be just fine. Live attendance is a form of fan engagement.

"This illusion that only millennials use YouTube isn't true. It's a pretty wide group of people that see content and distribute it on the Internet. We live in a world where there's thousands of opportunities for distribution."

In its current state, the DRL provides pilots with a new drone for every heat. This keeps the product fresh, but it also stalls some of the on-site experience. On top of that, in a setting like Sun Life Stadium, the course zips under tunnels and into concourse ramps, which means fans in the stands need the video board to see the action.

"At Monday Night Football, I'm spending 60 percent of my time watching the Jumbotron because enough thinks happen on the field that I can't perceive because I'm too far away," Horbaczewski says. "I'd say it's about 60 percent for drone racing too.

"No one goes to a Formula One race and says that was the best live race I've ever seen. This isn't Hamilton. It's a hard to follow race. We want this to feel like downs in football. There's a TV break."

Drone racing is similar to eSports. As Horbaczewski notes, both rely on technology (notably VR goggles), both started with informal gatherings and both are operating without full TV contracts.

But should drone racing align its approach more with traditional sports or eSports? Horbaczewski does not have the answers. Yet.

When asked if there was equal money to sign contracts with ESPN or Twitch, he said: "This is a bit of a dodge, but I'll be honest, one of the exciting journeys over the next year is finding who our audience is. This could be teenagers who are really into technology. It could be 25- to 45-year-old racing fans. Race fans have found us. It's been fascinating."

At the launch event, Horbaczewski and his staff were quick to hammer down the fact DRL is recruiting beyond the demographic of 18- to 29-year-old hipsters. The first batch of racers in Miami spread across age groups and included a father-son duo.

Steve Zoumas, who goes by the racing name, "Zoomas," is a DRL pilot by night. By day, the father of three co-owns a Long Island general contracting business with his brother.

"I think that's the future with all the technology and everything," Zoumas says of drone racing. "When you turn on the news, they're talking about drones, whether it's good or bad. We want to promote the good and show people it's not all just some idiot flying a drone in and around an airport."

Adds Horbaczewski of the diversity of racers: "I might be a stockbroker or unloading boxes at Macy's by day, but when I put on those goggles, I'm a competitor."

The DRL comes with comedic elements to its serious races. Drones do crash. After all, there is something fun about robots exploding.

"For some spectacular crashes for pictures, we loosen the bolts and we put some plastic parts on and fly them as fast as we can into something hard," says Tony Budding, DRL director of media. "The real crashes do happen, but we enhance the Hollywood fashion."

With the funding that it is pulling in, the league has the luxury of smashing its product into walls for buzzy social media hits. The obvious long-term goal is to establish a leading entertainment brand in America, and potentially worldwide society. It has a six-race season scheduled for this year. The Miami race will go live Monday, an abandoned Los Angeles mall is set for "Level 2" and three other regular-season venues are expected (Detroit, Mexico City and Auckland, New Zealand, are all in consideration). A world championship will cap off the inaugural year.

"There's an abandoned amusement park in Japan that I think you can just have the most epic race through," Horbaczewski says. "Sweden has a full subway station in Stockholm that's abandoned. You could carve an incredible track through there."

Horbaczewski can imagine all the courses he wants. The base of the DRL comes back to the simplest aspects of what racing fans -- specifically Nintendo fans.

"What did you love about Mario Kart?" Horbaczewski asks. "Everybody loves the red shell. Everybody loves the power boost. Everybody loves that when you crash, you're not out of the race. That little cloud just picks you up and puts you back. It's basically a time penalty. All those things are coming to DRL."

Three-dimensional, robotic, color-changing, racing machines whizzing through stadiums, malls and subway stations at 80 mph is crazy. And it just may be crazy enough to work.

-- Follow Jeffrey Eisenband on Twitter @JeffEisenband.