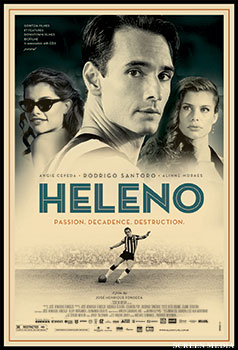

The film Heleno, starring Rodrigo Santoro and set for limited release Friday, chronicles the life of one of the biggest soccer stars in Brazilian history. Heleno de Freitas was the pre-Pele idol of the soccer-mad South American country. He played for the storied Rio de Janeiro club Botafogo, scoring a staggering 209 goals in 235 appearances. If the World Cup hadn't been cancelled in 1942 and 1946 due to World War II and its aftermath, Heleno might have been a world champion.

But this is not a movie about soccer.

Heleno was as troubled off the pitch as he was magnificent on it. He chased women, did drugs and drank in excess. Dead at 39, Heleno left a legacy that became embellished in Brazil until it was hard to tell what was real and what was not.

Now Heleno is as much myth as he is man. And that's precisely what attracted Santoro and director José Henrique Fonseca (below) to the story. They had the rare opportunity to re-tell the story of a legend to a generation that had only heard snippets of the tale.

"There weren't a lot of paparazzi, not a lot of social networks and all that," Santoro tells ThePostGame. "It was a different time, and this guy stood out like crazy."

Fonseca's film starts where Heleno's story ends. This is the part with which many Brazilians are familiar. His brain crippled by his longstanding use of the drug ether and his body torn apart by advanced syphilis, Heleno died alone and broke in a sanatorium.

After a particularly jarring opening scene in which a desolate Heleno appears on the brink of death, the movie transitions back to a wonderfully choreographed soccer game in which a young Heleno is masterfully controlling the pitch. The movie continues in that forward/backward fashion, slowly adding piece after piece of the story until the puzzle is complete.

In this way Heleno isn't a linear story. Rather, as Fonseca likes to say, it's a "mosaic."

"I didn't want to make anything lurid, I didn't want to shock anyone," Fonseca tells ThePostGame. "I just wanted to understand how a guy was trapped in his own behavior."

Heleno's reckless attitude, the same one that manifests itself on the pitch in ways both positive and negative, precipitates his social and emotional downfall. He tries to have it all: Chasing multiple women, drinking heavily and inhaling ether.

"He was like a prince among society," says Santoro, a Brazilian actor who is probably best known to American audiences as the Persian emperor Xerxes in 300.

These activities naturally intertwine and serve to accelerate Heleno's life. As the movie progresses, Heleno is going faster and faster, ever more recklessly. And when he is at his fastest he is literally speeding; in a car on the beach, where he proposes to his girlfriend Silvia (Alinne Moraes).

Heleno and Silvia's relationship becomes marred by infidelity and the agony of separation. Shortly after Silvia gets pregnant with their only child, Heleno is sold to the Argentine club Boca Juniors and forced to move to Buenos Aires.

The tragedy of Heleno is beautifully contrasted with a re-created Rio de Janeiro. Two centuries ago, when Napoleon stormed through Europe, Prince Regent João VI of Portugal fled to Rio and made it the temporary capital of his empire. During Joao VI's short stay, Rio was modernized and transformed into a beautiful South American cultural and intellectual paradise. This was how Rio appeared in the 1940s and 1950s, during Heleno's prime.

The city has changed drastically during the last half century, and not always for the better, so Fonseca spent months determining how to present Rio as the idyllic metropolis it once was. His work pays off in the form of lovely scenes on the beach and classic cuts of Heleno speeding through the streets of the city, with the mountains rising in the background.

Fonseca's decision to shoot the film in black and white, while not a popular one with Brazilian film financiers, also adds to the aura of the period.

The combination of Heleno's tragic cult hero and the film's black-and-white style have drawn comparisons to Martin Scorsese's 1980 classic, Raging Bull. Like Robert De Niro in Raging Bull, Santoro went through intensive preparation for his role: Not only did he take soccer lessons, he lost 28 pounds in a month-and-a-half and consulted with doctors on how best to depict a man dying of syphilis.

Because there is almost no footage and few teammates left from Heleno's playing days, Santoro and the producers spoke with as many witnesses of Heleno's tragic brilliance as they could.

"Everything that we heard in the interviews, it didn't matter if the person hated him or loved him, said good things or bad things about him, one thing that was most present was passion," Santoro says. "It was something that made me understand that this guy definitely left his mark. His presence was very strong, and whatever he was doing, there was something about him that people were intrigued by."

Surely, audience members will leave theatres with differing opinions on Heleno. And that is fine with Fonseca. Not trying to tell the definitive Heleno story, Fonseca was simply presenting the details and encouraging viewers to make their own determinations.

The myth of Heleno hasn't been eliminated with the release of the movie. In fact, now it may be stronger than ever.

"We heard so many bad stories [about Heleno], you wouldn't even believe it," Santoro says. "It's incredible. We thought, 'How are we going to paint this guy? This isn't a bad boy or a good boy, there's no such thing. How do we portray what he was going through in those situations? Why do you think he did that? Why did he react like that?' That was our work."

Heleno opens in New York, Los Angeles and Miami on Dec. 7.