This excerpt is from "Death Comes to Happy Valley: Penn State and the Tragic Legacy of Joe Paterno" by Jonathan Mahler. Copyright (c) 2012 by Jonathan Mahler. Excerpted by permission of Byliner Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

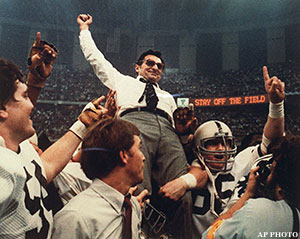

IN 1983, IT FINALLY HAPPENED. Thirteen years after being slighted by the president, Penn State beat Georgia in the Sugar Bowl and became the nation's No. 1 football team. On their return to Pennsylvania, the ninety-mile stretch of interstate from Harrisburg to State College was lined with fans cheering the team bus as it passed. On campus, fifteen thousand students packed the Old Main lawn for a pep rally. The chants of "We want Joe" brought defensive tackle Joe Hines to the podium, laughing. The emcee led the crowd in a new chant -- inadvertently coining a new nickname, too -- for the real Joe: He yelled "JoePa!" and they answered "terno!"

Paterno eventually came to the microphone. "We're number one, not only in football -- we're number one in many, many things, because we are Penn State," he said.

A couple of weeks later, Paterno rode through downtown State College on a snowy Saturday morning in a convertible Cadillac, the grand marshal of the official "Love Ya Lions" parade. Behind him, his Nittany Lions threw white souvenir footballs into the crowd from the back of a flatbed truck. Paterno was no longer just a cult hero; he was a national celebrity. The faces changed at the informal Saturday night dinners the Paternos traditionally hosted for friends and colleagues after home games. The crowd was composed, increasingly, of prominent alumni and other Penn State and VIPs from around the state. Paterno became friendly with Senators John Heinz and Arlen Specter and several other politicians. Maybe he was destined for a career in politics after all.

At the end of the 1986–87 season, Penn State got another shot at a national title, facing the top-ranked Miami Hurricanes in the Fiesta Bowl. In the intervening period, college football had exploded, thanks largely to an antitrust lawsuit brought by the universities of Oklahoma and Georgia -- with encouragement and financial support from Penn State -- against the NCAA.

The NCAA had long served as a middleman between the colleges and the TV networks, not only unilaterally determining which games could be televised but dispersing revenues from those games as it saw fit. In their lawsuit, Oklahoma and Georgia charged that this amounted to an illegal monopoly. A majority of Supreme Court justices agreed, striking down all of the NCAA's existing TV contracts. Teams and conferences were now free to negotiate their own deals with the networks, subject only to what the market would bear. The market would bear a lot. Three times as many games were televised in 1984 as in 1983. New bowl games also appeared overnight, complete with corporate sponsors offering huge payouts to participants.

The Fiesta Bowl agreed to pay each participant in its 1987 game an unprecedented $2.2 million. To set the game apart, it was played not on New Year's Day, when the big bowl games had historically taken place, but during prime time on Friday night, January 2.

Even before the two teams disembarked from their respective planes in Arizona -- the Hurricanes, infamously, in combat fatigues; the Nittany Lions in jackets and ties -- the storyline had been written. Just as the Nittany Lions were the defenders of the endangered "student-athlete" ideal, the Hurricanes represented an affront to it. As Paterno biographer Frank Fitzpatrick later described the matchup, it was "a showcase for all that was right and wrong with college football."

Everything about the two teams could be made to conform to this narrative. The Hurricanes wore gaudy green-and-orange uniforms; the Nittany Lions wore classic navy blue and white. The Hurricanes played in a major city, the Nittany Lions in a cute college town. The 'Canes were known for racking up penalty yards and running up the score. (They'd recently thrashed Notre Dame, 58–7.) According to the pre-bowl coverage, Paterno was still fuming at his team for earning a few late-hit calls during the season. Even their respective styles of play were easily made to fit their contrasting archetypes: The Hurricanes relied on speed and passing, the Nittany Lions on the more conservative approach of running and defense.

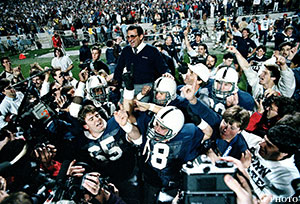

Fifty-two million people watched—a new record for a college football game -- as the Nittany Lions won in the final minute, stopping a late Miami drive with an interception on the one-yard line.

In many ways, the 1980s was Paterno's decade. It wasn't just the two national championships. The explosion of the college game was reverberating across the country, awakening once sleepy programs that were suddenly eager to access the piles of money and national TV exposure available to winning teams. Corners were cut, and scandals proliferated. The NCAA canceled Southern Methodist University's entire 1987 schedule, administering the so-called "death penalty" to the program after it was revealed that players were being paid through a slush fund approved by top officials at the school.

The more corrupt college football grew, the more it needed Joe Paterno. In 1986, he became only the second coach in the magazine's history to be named Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated. (John Wooden was the first.) "In an era of college football in which it seems everybody's hand is either in the till or balled up in a fist, Paterno sticks out like a clean thumb," wrote the magazine's Rick Reilly. The following year, the Philadelphia Inquirer's Sunday magazine put an even finer point on it: "Paterno is the only hero the sport has got at the moment," the magazine's editor wrote in a letter prefacing a 1987 cover story.

At Penn State, the cast turned over every few years as old players graduated and new ones arrived, but Paterno remained the one constant, outshining them all. His likeness was everywhere, from "Cup of Joe" mugs to "Stand-Up Joes" -- life-size cardboard cutouts that had become a popular item at tailgate parties. He was Happy Valley's beloved father figure -- JoePa. It was strange. You could still see him -- famous molder of men, coach of two national championship teams, bulwark of integrity against the polluted waters of college football -- walking to campus in his khakis and navy windbreaker, as if nothing had changed.

Was it possible that nothing had?

-- "Death Comes to Happy Valley: Penn State and the Tragic Legacy of Joe Paterno" by Jonathan Mahler is available on Amazon.com.

Popular Stories On ThePostGame:

-- Slideshow: Joe Paterno Through The Years

-- Did Media Get It Wrong On Joe Paterno?

-- Time To Strike Against The NCAA

-- Still Scarred By Two Wars, American Hero Daniel Rodriguez Chases His College Football Dream