You will not die tomorrow.

You repeat this to yourself as your withering body greets the procession that stamps its way over the shiny white floor to your bedside to say goodbye.

Your brain's been leaking blood for two weeks, but you're still sharp enough to have convinced yourself that it's the opposite. They're saying hello, dammit, and you'd swear by it, and you say out loud how nice it is that so many of them are taking the time out of their busy days to do it.

Your father rubs his eyes. The flight from Germany has caught up to him early. Your mother, who lives down the street and has been with you since the stroke, sits in silence, watching over you through the glass walls that separate you from innumerable machines and workers dressed in white.

Your daughter, Megan -- 16 years old, if you can believe it -- comes in and out of the frame. She never seems to stop moving, taking care of something, gathering the latest information. She's in control of this whole gig. Your open heart surgery, your two bouts with cancer, now this. She's seen as many cold, sterile corridors as you.

The rest of them keep filtering in. Your twin sister, Kirsten. The rest of your relatives from Boston, where you grew up. Your infielders, your pitchers, your AA sponsor.

Faces, sometimes clear, sometimes blurred, depending on the hour. Faces you've shaped into smiles with ease in the past -- just an inappropriate joke away -- not smiling today. You're sure they think they're not allowed to. Normally, you might tell them they're wrong. But you'll save that energy for tomorrow.

You've had two heart tests already today, and they show that the infection of the artificial valve that was put in three years ago has caused swelling. The minor stroke that landed you in this bed two weeks ago had you slurring and unable to move for a few days. The doctors had to wait out the bleed as long as they could before pumping you full of thinners that would let them go back in and replace the bad valve.

Megan told you this and you nodded at the words, but here you are: cracking wise, staggering around the ICU with a walker. It's nothing new, this mantra: fall down seven times, get up eight. It's the chorus you wrote, one of your favorites to sing, and when you leave this hospital, you'll sit down at the piano and belt it out louder than ever.

The visitors continue to march in. To them, you're the classic hard-luck pitcher, the guy who's already labored into the extra innings of life, scattering a run or two but doing all he can to keep himself and his team in the game.

You don't have the energy to tell them it won't go down like that this time, that you've got a lot more left in that 52-year-old right arm. So you'll do what you always do. You'll get up.

You rise and look out the window of your enclosure. There's no view of the Victorian rooftops or the hills rolling their way to the Golden Gate to fill you with get-well-card nothings. There's not a lick of sun in sight. This comforts you more than the kind words of a nurse or the wisdom of a daughter who has become a woman before you, maybe in this very room, and you smile, knowing there are still two things you can be sure of.

The fog never lifts before noon in San Francisco in May.

And you, Stefan Matthew Wever, will not die tomorrow.

Errant champagne spray, white dots of beer foam, thick plumes of cigar smoke and a mass of bodies, still in sweat-soaked jerseys, mixing together, rolling around in the damp, ripe carpet. Teammates hollering, posing for pictures with index fingers raised, and drinking the fatigue away. It might have been the ultimate baseball cliché, but on that night, Sept. 11, 1982, it was their cliché.

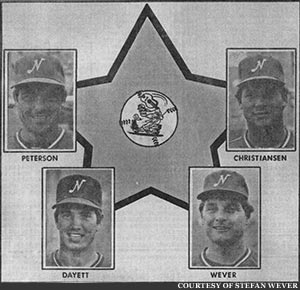

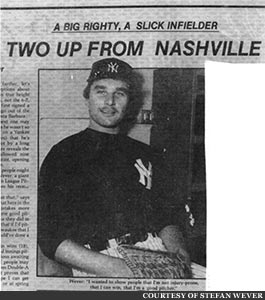

The Nashville Sounds had just beaten the Jacksonville Suns for the Southern League title, and the tiny clubhouse at Greer Stadium was being ripped from its Double-A moorings, floating up through the soupy Tennessee air to heaven. Stefan smiled, overseeing his first real victory party while standing in the middle of the room, the quaking celebration's six-foot-eight, 240-pound epicenter.

He was the team and league MVP. Sixteen wins in the regular season and two more big ones in this playoff run. An earned-run average of 2.69. More than 200 strikeouts. And, better than all of that, the stirring notion of what might be to come in George Steinbrenner's Bronx.

He had been patient, never resting to think about what it would feel like to climb atop a pitcher's mound before 55,000 with the 4 train rumbling in the shadow of the big courthouse and the lights -- so many lights -- bouncing off the timeless white of the façade. He knew the 1982 Yankees were playing out a pathetic string and that they were pitching-poor. But he also knew that his command of a 95-mph fastball, his diving forkball, his improving changeup, the health he'd shown throughout the summer and his growing maturity had made him their best young arm.

Still, this was the New York Yankees, and Stefan was still in Double-A. Which meant that he'd drag his suitcases, his baseball bag and a major league hangover to the airport later that morning, catch a flight back to San Francisco, finish his Bachelor's in English at Berkeley during the winter, and meet his buddies again the next March in Fort Lauderdale for spring training, where he planned to lay claim to the No. 1 spot in the rotation for Triple-A Columbus before the poor catcher even felt the sting of his first heater. One more good year and he'd be primed for the big club. No, make that the biggest club.

Stefan was only 24, but he'd seen his share. Watching him on the mound, fans and opposing hitters might have thought everything came easy for him, but his awe-inspiring numbers at Lowell High School didn't inspire much awe from college recruiters. Their reports read that he was pitching against a bunch of San Francisco stiffs, so his masterful senior season and the two-shutout doubleheader against Lincoln only got him as far as UC Santa Barbara -- a dot on the Division I map known more for gnarly surf breaks than championship hardball.

But after you fall down, you get up.

He toiled in the classroom, set on achieving straight A's to keep up with the throng of MAs and PhDs that had been springing from his family tree for generations. He pitched well enough against the big boys on the Gauchos' schedule to rise above overmatched teammates and the school-record 17 losses they hung on him. By his junior year, he was a legitimate scout magnet, and while minor elbow problems and the fear that they would some day become major kept him out of the first round, the Yankees came calling in the sixth.

Raised in Boston until he was 12, Stefan never imagined he'd feel anything but defiant hatred of everything pinstriped. Yearly communal suffering amongst his Red Sox brethren was a birth right. Playing for the Yankees? Ha! That would never happen.

But in 1979, the dastardly Yankees were offering Stefan a signing bonus of $15,000. He held out for $16,000, and soon enough he was off to rookie A ball in the upstate New York hamlet of Oneonta, the beginning of the climb to a dream.

Crisp Oneonta spring nights bled into steamy summer ones in high-A Fort Lauderdale. By 1981, Stefan had made it to Nashville by way of cruising through lineups with an ERA of 2.00 and 80 strikeouts in 81 innings.

Teammates were from all over: sons of Iowa farmers, Bible-belters, ghetto survivors and poverty-stricken Dominicans. Stef was the left-coast liberal, often the lone voice crying in the wilderness of 10-hour bus-bound arguments about abortion, homosexuality and the death penalty.

He learned how to keep it civil. And he learned that success in pro ball, as in life, is about how you get up after you fall down. The examples, and the cautionary tales, were close by. Todd Demeter, the Yankees' second-round pick the year Stef was drafted, got more than two hundred grand, a record bonus at the time (the rumor was that four Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises were part of the deal). He was a big outfielder -- six-foot-four, 200 -- who was expected to get bigger and hit towering home runs for Yankees World Series winners for years. Todd's father, Don, played 11 big league seasons in the 1950s and '60s. Todd had the pedigree and the right-handed power.

But as the steadfastness of his Christian beliefs grew, so did his strikeout total. He'd saunter to the plate with two runners on and two out and the team trailing by a run, pop out to the second baseman and walk back to the dugout in what seemed like a blissful trance of serenity. He was out of organized ball after seven seasons, having never made it past Double-A.

Then there was the skinny 18-year-old from Indiana who was picked in the 19th round of that '79 draft. Stef and the rest of the team would cringe while watching the hapless Hoosier flail his way through batting practice in Oneonta, barely getting the bat around on rookie-league fastballs. But something about this kid was different. An engine burned hot inside, incapable of slowing down. Donnie Mattingly was sure he'd be a big league star, and his exhausting sessions in the batting cages and on the back fields of baseball outposts made sure he was right.

And Stefan? When he arrived in Nashville, he was still a typical wild hard thrower as capable of walking six batters as he was striking out 12. He got by because of weak competition -- all the stuff and no clue how to use it. When he got hit hard, he'd look for any excuse. A slippery mound because of the previous night's downpour. A sore neck because his roommate loved to crank up the air conditioner. A bedeviling inability to grip the ball because of the sweat caused by the humidity. None of it mattered to his Double-A pitching coach, Hoyt Wilhelm, a 60-year-old Hall of Famer who made it through 21 big-league seasons with nothing more than a knuckleball and some serious guts.

It didn't take long for Hoyt to teach Stefan all he'd need to know. The salty coach didn't care about the pressure points of fingers on the seams of the ball or pronation or optimal leg positioning or repetition of delivery. He cared about one thing: what was going through a pitcher's head while he had the ball in his hand. "Just grip it and throw it," Hoyt would say, and the frankness of his gaze and the certainty of the cadence of the words were enough to belt any pitcher in the jaw with how simple it all seemed to be.

All Hoyt wanted was for his guy to battle, to know that the talent in his arm was good enough and the power of his conviction -- the confidence to take that arm and go right after hitters without hesitation and without fear of failure -- was everything else. "When a guy makes it to first base," he told Stef, over and over, cracking a Cooperstown grin, "you want him to turn right, not left."

Stefan had listened, and now the Nashville Sounds were champs and the big righty was presiding over a serious party that had no end in sight.

It was around midnight when the clubhouse boy tapped Stefan on the shoulder, pointing him to the closed door of the manager's office. Johnny Oates sat behind his desk, and Hoyt, still wet from champagne, pulled up the chair next to Stef. Both elders had glares etched into the faces that would feature kind smiles of encouragement on most days. Their grim silence told Stefan something was wrong. "Weve, I'm sorry to have to tell you that there's been a change in plans," Johnny said. "You won't be seeing any of your friends at the airport when you arrive tomorrow." Stefan didn't catch on right away, but a slight twinkle in the manager's eye gave him the opening to play along.

"Why's that, Johnny?"

"Because you'll be landing at JFK on your way to Yankee Stadium."

The grown men hugged and laughed and cried. Hoyt told Stefan that no one had ever deserved it more. Stefan walked back by the lockers in a daze, shook hands, packed his things, opened the door that led outside and walked into the still-warm early-morning air of a lifelong dream.

In 1964, when Stefan and Kirsten Wever were 5 years old, their mother and father went to see a matinee of "A Hard Day's Night." Mom, Dorothy, was a piano player, chamber singer and music teacher. She wanted to see what The Beatles hype was all about.

On the way out of the theater, the Wevers bought tickets for the whole family to see that night's late show. "You need to hear this music," she said, with a seriousness he hadn't seen from her. The next week, Dorothy showed Stefan a C chord on the piano. The week after that, a C minor. The week after that, a C7, and so on. He was hooked on all of it: music he could hear but also touch and make his own; the work and time that would go into to mastering those eighty-eight keys; the innovative melodic progressions, lyrics, instrumentation and personalities of John, Paul, George and Ringo, whom he was convinced had descended in a spaceship, just so happening to crash into a cobblestoned street in Liverpool where a few guitars had been left out with the previous night's rubbish.

He hopped into the taxi at the airport curb 18 years later, almost chuckling while telling the driver, "Yankee Stadium." Then a pause. Then, with appropriate dramatic emphasis: "Players' Entrance."

He looked out the window at a cloudless sky, perfect for the Sunday afternoon game that had already started, and allowed himself to wonder, just for a second, what his big-league locker might look like. This time he let the chuckle happen.

The cab rumbled along over potholes. The only noise escaping the front of the car was incoherent Brooklynese barking from the intercom, but if Stefan were to sit back now and soundtrack the scene, he would cue up some Fab Four right as The House That Ruth Built came into view. "Why leave me standing here?" Paul would sing at that instant. "Let me know the way."

The astonishing thing was how the way already knew him. His feet had hardly hit the pavement (not that he noticed) before he saw them crowding around him, already asking for autographs. Stef couldn't sign because he was holding eight months of clothing in five pieces of luggage, but he heard them. How could he not? They knew how to pronounce his name. They recited his numbers from Nashville. "Go get 'em, big guy," they shouted. He told them he would.

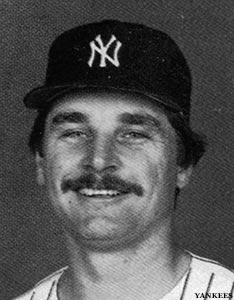

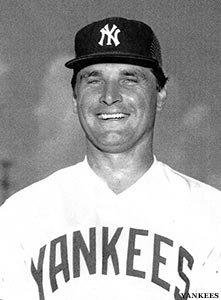

It was the second inning out on the field of the old ballpark as he navigated the dark basement corridors within. The empty clubhouse spread out before him like a cavernous jewel box. He had figured on a locker in a marooned corner, maybe by the toilets, and a uniform number of 93 or 84 or something fitting for a former spring training afterthought who might only be in the Bronx long enough to notice the graffiti.

And then the whirlwind: His locker was in between Dave Winfield and Goose Gossage, two players headed for the Hall of Fame. He had No. 25, last worn by Tommy John, who'd been an All-Star three times and already had close to 20 years in the bigs. He suited up in slow silence, savoring the feel of the cloth, before walking through the tunnel to the light of the dugout. He first saw Sammy Ellis, the Yankees' pitching coach, whom Stef had worked with in instructional league a few years back. Ellis introduced him to the manager, Clyde King. He spent the rest of the day rooting for men he didn't know, faces from TV and baseball cards that had come to life as they descended the steps before him and slapped his hand: Winfield, Ken Griffey, Graig Nettles. The Yankees beat the Brewers 9-8 in the bottom of the ninth.

Winfield and Gossage, when not besieged by writers whose beltlines encroached on Stefan's limited space, were friendly neighbors, tossing chit-chat his way. Ron Guidry, the staff ace, the former Cy Young Award winner, walked over, extended his hand and said, "Welcome to the New York Yankees."

On the charter flight to Baltimore that night, Stefan was handed his meal money: more than $600 for the long road trip ahead. He watched his new teammates as they pulled out their money clips, almost in unison. He would have to get a big-league money clip, now, wouldn't he? He'd also have to buy new suits. Six-foot-six Winfield spent the flight listing the best Big & Tall stores in the cities of the American League.

It got even better at the hotel, a luxury high-rise. Stef was supposed to room with Jay Howell, a rookie up from Triple-A, but the team's traveling secretary, Bill "Killer" Kane, pulled him aside to tell him the team's backup catcher, Barry Foote, was taking a hiatus to be with his sick wife. Would Stefan mind taking Foote's room? Why, no, he wouldn't.

And, man, that room was something -- an ornate suite that overlooked the Inner Harbor. A gold-plated telephone hung from the bathroom wall. And his luggage, which he hadn't touched since arriving at Yankee Stadium that morning, was waiting for him in the front hallway. He turned the light on, took off his shoes, laid down and stretched out his long legs, sighing and thinking he might take a nap just for the hell of it -- to see if he'd really wake up in the same bed and the same body.

But the word was out, a serious poker game was on, and it didn't matter who had done the inviting. Stef was the host. Room-service beers and snacks arrived as if on a conveyor belt as the players filtered in: Lou Piniella, Bobby Murcer, Oscar Gamble, Willie Randolph, Jerry Mumphrey, Winfield, Gossage, Nettles. Stefan bluffed when he shouldn't have, forking over hundreds from that first big league paycheck he hadn't yet received and laughing through it all.

Sammy Ellis stopped by and Stefan told him his arm had never felt better, forgetting the fact that he was at over 230 innings for the season and that he had logged routine pitch counts of 130 and higher in most of his starts. "Don't worry, Stef," Sammy said. "You'll get in there soon."

Stefan cleaned up the party and watched the sun rise over Baltimore. He wouldn't be able to sleep for hours, but he didn't care. It was a night game, he was in the major leagues, he was the top prospect for the New York Yankees, and nothing would ever stand in his way again. He didn't think it. He knew it.

Years after his career was over, Stefan Wever decided to write a book.

His life had become so extraordinary that it had to be documented, and why not? Stefan had always been able to write songs, to find the right words to go along with the piano riffs that would come to him at odd times -- in the car or the shower or right before falling asleep. So he could do this, no problem.

But first, he'd need a title. He chose one that seemed to say it all, "My Right Arm," and began.

When I awoke on Friday, September 17, 1982, I felt like an 8-year-old on Christmas morning. It really set in when I opened the sports section of the paper (delivered, naturally, to my "suite") and went to the listing of Today's Starting Pitchers and saw: New York (Wever 0-0) at Milwaukee (Caldwell 15-11), 7:30 p.m.

I spent the day wandering through some super-mall in downtown Milwaukee feeling pretty good about myself. I bought some things with my newfound wealth (meal money) that I would never have considered buying the week before, like $50 sunglasses. I tried not to think about that night's game, but I didn't have much luck. Everywhere I went, I saw Milwaukee Brewers paraphernalia, and everything I read talked about the incredible offensive prowess of the team (something I would find out about first-hand a few hours later).

It had rained most of the day in Milwaukee, and we weren't sure if there was going to be a game. Some of the guys had assumed we wouldn't play because weather conditions were still bad in the afternoon, so they made tentative plans to go out that night. We finally got the word that the game was on, although batting practice had been canceled. All that meant was that I had more time to lounge around the hotel and think about the game.

By the time we got to Milwaukee County Stadium, I was ready to go. I received a few words of encouragement from some of the guys, while others left me to my own thoughts, either out of courtesy or because they didn't know or didn't care. The other pitchers knew, however, that this was the biggest night of my life.

Stefan wrote on and off for a year, describing his arrival at the chilly, misty ballpark and the mud-slicked mound he would be tasked with digging into and pushing off of for what he hoped would be all nine innings. As he pressed the pen to the notebook page, he took the reader with him into the bullpen, where he warmed up with such nervous wildness that he forced himself to pretend he was in Nashville again, staring in at the glove of a Double-A catcher. He wrote about making the slow stroll to the dugout and sitting there, dazed, while the top of the Yankees lineup went in order against Mike Caldwell.

Before I knew it I heard my name being announced as the starting pitcher for the New York Yankees, and my teammates were going out to play defense. I walked out to the mound slowly. This was it!

He put his pen down, not inspired or awake or confident enough in each detail, save the ones that still stuck him in the side like a jagged knife. He stashed the book on a high closet shelf after 15,000 words, figuring he'd get back to it when his schedule cleared and he could devote the energy and perspective that it deserved.

He never finished the book.

Stefan would be one of the few -- maybe the only -- pitchers to start his major league career facing two future Hall of Famers. It started when Milwaukee's leadoff man, Paul Molitor, stepped into the batter's box ...

A scalding surge of adrenaline.

I'll bet I can throw it a hundred tonight.

But Molitor gets enough of a pitch to send it through the right side for a six-hop single.

OK, fine. No problem. Get the next guy.

The Brewers' No. 2 hitter Robin Yount digs into the wet dirt by home plate and lashes a no-doubt double to right center. Molitor scores, and the Brewers lead 1-0.

Oh well. No shutout. Get the next guy.

Cecil Cooper. Stef throws him a good changeup, but even though Coop is fooled by the slower offering, swinging way too early and way too hard, the bat still catches the bottom half of the ball and lofts it to shallow left center. Stef cranes and looks behind him, sure he's gotten his first out, and watches in silence as Mumphrey breaks back as if it's going to the wall before realizing his mistake, charging, and overrunning the ball, which had dropped onto the soggy turf.

Shake it off. Do what Hoyt would do. Battle. It starts with a good pitch right here.

Ted Simmons steps in and more rainy-night blues ensue. Simmons hits a routine ground ball that skips under the legs of the shortstop, Andre Robertson, for an error that should have been the second out. Cooper lumbers to third.

Ben Oglivie flies out, but there are still runners on the corners with the American League home run leader Gorman Thomas striding to the plate wearing a scowl out of a Rapid City saloon.

Fastball, high. Ball one.

Changeup for a strike.

And then the twinge.

It's in his right shoulder. It's not a pop and it's not a burn. More a little tug, enough for him to know something isn't quite right. It doesn't hurt, but it's there. It's not going away.

Stefan stops for a second, walks to the back of the mound and leans down for the rosin bag.

No way in hell I'm having the trainer come to the mound during my Major League debut. No way they're going to peg me as the soft-hearted, injury-prone complainer I was made out to be before Hoyt toughened me up.

He focuses on the catcher, Rick Cerone.

Two pitches later, Thomas hits one over the fence.

Dammit. These guys just don't stop.

With his arm hanging like overcooked linguine, Stefan somehow retires the next two hitters but exits the first inning with his team losing 5-0.

In the top of the second, Piniella lines a ball to left field that looks like a double to start a rally, but Oglivie dives on the sopping grass and comes up with it. Caldwell, a soft-tosser, gets out of the inning unscathed, prompting a near-fit from Piniella in the dugout. Piniella paces up and down the concrete walkway in front of the bench, barking to himself about how a no-good pansy like Caldwell should never have gotten him out. He stops in front of Stefan, who's staring into his own bad fog. Piniella points to Stefan and addresses the team.

"You see this guy? He's making his goddamn major league debut, and you guys can't make a single play for him," Piniella says. "The other team makes those plays. That's why they're going somewhere and we ain't doing squat."

Nobody answers him, but Stefan is jerked out of contemplation and brought right back to the cold, hard bench, the water collecting on the dirt of the first-base line and the unexpected benevolence of a teammate he hardly knows. He nods his thanks at Piniella and charges up the steps.

The rest is a mixture of increasing raindrops and plummeting hopes. He throws three wild pitches. He gives up eight hits. He walks three batters. Twice he has chances for double plays, and twice the second baseman, Randolph, can't make the throw to first to finish them off.

With two out in the third and the Yankees trailing 7-0, King trudges to the mound, and Stefan knows why. Clyde sticks out his hand and Stefan hands him the ball.

"Not a bad job," Clyde says. "It wasn't all your fault."

Clyde pats him on the rear and Stefan walks back across the infield. As the rain continues, the stadium lights seem to dim.

And it's over. Just like that.

Stefan Wever loved to talk about adversity. It was the lesson he gave the pitchers of the Redwood High School varsity baseball team when he coached their first game in 2009. On that perfect March day, with the tree-lined peak of Mt. Tamalpais framed against the bright blue Marin County sky, he soaked in the warmth of the spring sun, his boys rapt on aluminum bleachers, and spoke of the events that had conspired to bring them together.

He told them about his Double-A season in 1982 and how much he had failed: the six losses; the nine home runs allowed; the more than 80 walks; the seven wild pitches. Then he told them about how much he had succeeded: the 18 wins; the 200-plus strikeouts; the Southern League title; the call-up to the Yankees.

He left the story there, giving the young athletes a fitting parable of how optimism and the ability to rebound from life's low points identifies character and defines what it means to be a winner. "It's not how you fall down," he told them. "It's how you get up."

Stefan Wever didn't tell them everything.

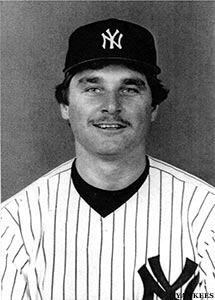

He didn't tell them about the aftermath of that night in Milwaukee, when the twinge in his right shoulder turned out to be a torn rotator cuff and torn labrum, when the two years of conservative rehabilitation at the behest of the Yankees took his 95 mph fastball and nine-inning durability and turned it into 85 and five, tops.

He didn't tell them about how he arrived at spring training in 1983 and the Yankees' new manager, Billy Martin, took him aside and said, "Stef, you're gonna be my No. 5 starter." That year, Stefan pitched only seven games at Triple-A and put up an ERA of 9.78.

He didn't tell them about the shoulder that never seemed to improve, even after rigorous offseason workouts, and limited him to seven games back in A ball in 1984. Then came the two-years-too-late surgery and the five-game comeback attempt with Double-A Albany-Colonie in 1985, throwing through pain until he made a final, crushing decision, picking up the phone one morning and dialing a familiar number in San Francisco.

"Mom," Stefan said, staving off tears, "I'm coming home."

The Redwood Giants didn't need to hear the details of the ensuing 23 years -- 23 years that had led their new coach to this motivational moment overlooking infield grass still damp with dew, but they could figure it out for themselves with Google and a free hour.

Stefan had wandered the hilly streets of his hometown looking for a new career and a new passion, but he often ended up escaping the fog of his deferred dream by finding a barstool instead of a use for his English degree from Berkeley.

He met a kind and gorgeous woman named Melinda and married her in 1988. Three years later, he and a friend turned their mutual admiration for the comfort of booze and dark places into a business. It was the Horseshoe Tavern on Chestnut Street in the Marina District, a yuppie phoenix sprouting from the ash and rubble of the Loma Prieta earthquake. Liquor flowed, money followed, and Stefan and Melinda, no longer worried about rent, bought in the lush, suburban hot-tub paradise of Marin.

Astute patrons who connected Stefan's Yankees portrait on the wall of the Horseshoe with the older, super-tall athletic guy pouring doubles behind the bar might strike up a conversation. They might end up likening the proprietor to Sam Malone, the big-league pitcher-turned-barkeep from "Cheers." Stefan got a lot of Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, too. That was Burt Lancaster's character from the movie "Field of Dreams," the one who lamented the fact that he had played only one game in the major leagues.

A few wiseasses full of Anchor Steam might even quote the flick, spewing forth hacky Lancaster mimicry before the rolling eyes of Stefan. "You know," he says, "we just don't recognize the most significant moments of our lives while they're happening. Back then I thought, 'Well, there'll be other days.' I didn't realize that that was the only day."

When he was feeling philosophical, Stefan compared his plight to that of a hypothetical Luciano Pavarotti who'd ruined his vocal cords on his first night as a tenor. "That's how I look at it," he said in an article on MLB.com. "It might be egotistical, but that's how I have to look at it."

If he wasn't looking back, he was looking sideways, never ahead. Megan was born in 1993, but the responsibility didn't stop Stefan from searching for his life's direction at the same old parties. It wasn't shocking, then, that Stef and Melinda had split up by the time their baby girl was 7.

One night when Megan was 12, Stefan, as usual, stayed at the Horseshoe, getting a solid heat on after hours with countless Miller Lites and a few bumps of cocaine. Next thing he knew, it was 10 in the morning and he was back in Marin, looking for his house. He hadn't even seen the police car until he had to stop. Did he run a red light? Well, probably. That's what the cop said, anyway.

It was Stefan's third DUI. He was facing prison -- automatic sentencing in California -- but he had a plan. He quit drinking and drugs that night, entered Alcoholics Anonymous and got a six-month ankle bracelet instead of a six-month cell.

Fall down? Sure. Get up again? You better believe it.

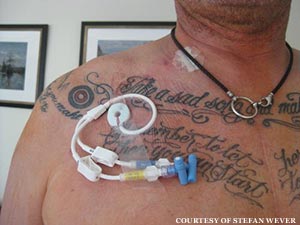

Stefan had considered sharing the bullet points of that R-rated curriculum vitae with the Redwood team on that March morning four years after he got sober. He'd thought about telling the boys they were getting a leader who had risen from the depths -- a man who'd lived up to promises, staying clean and serene and recommitted to reaching his potential. He'd thought about telling them that he was taking care of himself better, too, having had open-heart surgery in 2007 to replace a defective aortic valve. "I'm still not a perfect human being," he'd thought about saying, "but I talk a good game."

He'd thought about mentioning that he was playing piano again, writing songs and popping up at Café Bazaar near his bachelor pad in San Francisco for open-mic nights. He didn't bother offering them copies of "The Gardener," the full-length CD he had cut at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley at the end of 2008. In fact, if he had a Steinway sitting in front of him on the third-base line, he could have launched right into lyrics – "I felt so fragile, my suffering I can't overstate/But then I looked ahead and I finally stood up straight" -- that he was sure would have connected better with these malleable minds than the timeworn platitudes of any speech he could deliver.

But he'd decided that all that stuff would have to wait. A season was beginning, he was a varsity coach for the first time, and he wasn't going to lay too heavy a trip on these guys too soon. They had ballgames to prepare for. They had a team concept to buy into. It was time to take a losing program and make it a winner. Fast.

And he did it. When May rolled around, the Giants were playoff-bound, having already won 14 games in a season in which many of the parents and administrators expected five or six. The players listened to Stefan. They learned from his experience.

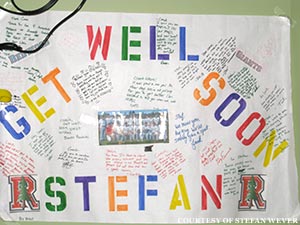

Of all the things he could have told them that he decided to blow off for their own good, there was one piece of information he couldn't hold onto any longer. On May 13, 2009, before a road game, Stefan summoned the boys down the right-field line. Everyone took a knee, and their coach explained why he had missed some practices. He explained why he had lost 40 pounds during the last few months. He explained why the gland in his hip was so swollen and infected and why he would have to leave the team the next day.

Stefan had been diagnosed with a rare, ultra-aggressive form of cancer called anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Even if the intense chemotherapy he'd soon face knocked it out, there was no guarantee it wouldn't return. The boys didn't cry, and Stefan pleaded with them not to. He was going to beat this and he'd be back coaching them the next season.

The Giants played hard that night, but they lost.

Megan Wever was blessed with her father's sense of humor. OK, maybe blessed isn't the right word -- burdened, cursed, hell, even doomed might have been more fitting. Stef always had a knack for saying the oddest, most off-putting thing at just the right -- well, wrong -- time. If you didn't know him, you might think he was looking for a brawl instead of good old shock value.

In a San Francisco Chronicle survey of random people on the street called "Two Cents," Stefan added a lot more than his when posed this question of the day: "What do you use your garage for?" His answer: "A BDSM dungeon."

In another, he and 10 others were asked, "What's your favorite place to visit in Southern California?" He deadpanned, "The departure terminal at LAX."

Maybe Megan didn't know how much she was like her dad until the afternoon she walked into the hospital room right after the diagnosis. He repeated the four strange words that had attached themselves to his body and mind forever: anaplastic large cell lymphoma. He told her what they'd told him -- that this type of cancer accounted for only 1 or 2 percent of all lymphoma cases.

Hell-bent on doing whatever she could to cheer him up, she looked him square in the eye, the man she'd always known as her "forever daddy," and let loose with the first bit of positivity she could muster: "Well, at least it isn't testicular."

He laughed as she knew he would, and she laughed, too, and maybe that was enough to get them through the day. Stefan knew that if McCartney were around to pick a line to sing, it would be, "Take a sad song and make it better," and here was his 16-year-old daughter doing just that.

She was there at Kaiser when chemo began in June. Stef told her it felt exhilarating, like it was the night before a crucial start. Soon he'd have the ball in his glove again with a chance to get a win: three months of CHOP, a four-drug cocktail designed to rid the body of the lymphoma. If that worked, the next step would take place at Stanford University in early September, where Stefan would be given a chest catheter and undergo preparation for a procedure that would remove his own bone marrow, clean it out, and let healthy stem cells "harvest" before being put back into his body. If that didn't work, nothing would. If it did work, he'd be home, cancer-free, for the holidays. He told her it wouldn't kill him, wouldn't even break him. He meant it.

One night in late June, home after the day's chemo and a week removed from his first post-diagnosis haircut, Stefan sat at the piano in his living room, playing a ballad in a minor key. He heard Megan creep into the room and sit down behind him. He knew she was watching as his nimble, elegant fingers found the right keys without effort and massaged them in perfect time. A lilting melody overtook the room and everything else. She began to cry but tried to hold it back, pretending to sniffle, clutching at the idea that she could still be the Megan he had taught her to be: ready to attack challenges with a stoic, hardened face that would shout at the world that she couldn't lose. No fear out there on the mound, or in life. No excuses. No tears, if you could help it.

She couldn't. She let go and he stopped playing and sat by her side, holding his little girl who had only so much courage left. He pulled her close.

"Megan, I'm your forever daddy," he said. "Nothing could ever take that away. Nothing will."

Megan stayed by his side. Dorothy helped navigate the new world of dietary specifications. Melinda provided rides and rediscovered companionship.

The chemo worked, and in September Stefan began injections of a drug called Neupogen that pushed the stem cells into his blood for the upcoming harvest. Then, another win. And again, Megan was there at his side, this time at Stanford in October, when the bone marrow transplant was deemed a success and Stefan was sent home for a month with almost no working immune system, wearing a mask that made him look like Darth Vader.

On November 5, 2009, Stefan's doctor told him (and Megan, of course) the good news: there was no more cancer in his body. He was at home and happy, already plotting out the starting lineup for the following Redwood season. He had gained back more than 20 pounds. Megan, who had transferred from Redwood to nearby Tamiscal High School where she was working on an independent-study-based curriculum that allowed her to be her father's 24-hour caregiver, was holding a 4.0 GPA.

Three months later, on Valentine's Day, the father and daughter were in the car, rolling down Geary Street to Dorothy's house for dinner. Stefan's cell phone rang, he answered it and pulled over. Megan wondered why he didn't play the call through the car's speaker system like usual, but she didn't ask him about it. He said everything was fine.

He was quiet at dinner until he broke the news to Megan, Melinda and Dorothy. The cancer was back. The women cried, but before he went home he swore he'd be OK. He'd make it through this, too. His doctor had mentioned a drug called SGN-35, not yet approved by the FDA, that he could receive instead of chemo. His oncologist told him that it had yielded good results so far. He said he couldn't wait to give it a shot.

Five days later, Stefan was approved to receive SGN-35 at Stanford as part of a clinical trial. He would take one pill each week for three weeks, take a few weeks off, take the pill again for three weeks and undergo radiation. Then he'd have another bone marrow transplant, but this time with marrow from an outside source. And he had a perfect match: his twin sister Kirsten.

"We're going into extra innings," Stef emailed a friend, "and I've always been pretty good in those situations."

By April, the cancer was gone again. The SGN-35 had been so effective that he didn't need the bone marrow transplant. It was tough for him to get out of bed in the morning, but he made it to practices and games. He lagged at the field, but the team did not. The Giants were winning. They were on their way back to the playoffs.

In the dark early-morning hours of April 28, Stefan woke up and got dressed, ready to head to the field. He walked into Megan's room and told her he was going to practice. She looked at the clock. It was 3 a.m. Before she could ask him what the hell he was talking about, she heard it. His body, back to its 240-pound playing weight, had fallen to the floor like a cut sequoia. He was next to her bed, breathing heavily and slurring. He couldn't get up, but he was trying and slipping down again. Megan had no prayer of lifting him, but she remembered one thing she had read during the long days of cancer recovery: that a 99-degree temperature or any other slight abnormality could mean death. She told him to stop trying to get up because he would hit his head.

She called 911 while he spit out incoherent insults and demands. Megan kept calm and explained in a clear, strong voice what was happening. Six paramedics arrived and put Stefan in a special chair. Megan called Melinda and the two got in the car, following the ambulance to Kaiser, where he was taken up to ICU, motionless, expressionless.

And barely alive.

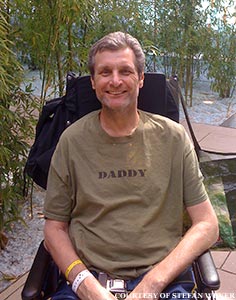

You love San Francisco because it's yours.

When you rise at 6 in your Inner Richmond house and you can't see the car parked across the street, you feel like the all-encompassing fog was placed there to enclose you in an impenetrable force field. You can operate on your terms in this crazy metropolis of hills and forests and bay and ocean and houses piled on top of each other -- it's the only claptrap chaos you've ever seen that makes any sense. You can take care of the necessities of the day with every purposeful stride. And believe it: you are striding again.

You knew you'd wake up that May evening in the room with no view, and you were right. And now, more than a year later, you're still here. The valve-replacement surgery after the stroke, the one everyone but you was sure would kill you, the one that got your father on a plane from Germany to say goodbye when you were convinced he was just saying hello -- it took nine hours. But Megan and Melinda were watching as you opened your eyes, and they heard you say something offensive the next day and knew there was no brain damage. You were back.

Maybe it was just another miracle, you surviving two go-rounds with cancer and now a stroke. McCartney would have sung right there on that ICU floor that in your hour of darkness, there was still a light that shined on you. He might have added a line about how much more work was in front of you. "No problem," you'd tell him. "Good things are ahead."

Like this: Two days before you were moved to a rehabilitation facility in Vallejo to regain the strength on your left side, redevelop muscle tone and reclaim your ability to write, type, speak, your Redwood Giants beat Drake 7-3 to win the Marin County Athletic League championship with your jersey hanging outside the dugout. The boys came to your bedside at Kaiser that weekend and brought you the pennant, hanging it next to the Red Sox banner Megan had pilfered from a nearby saloon.

And this: In early June, Megan graduated from high school. She was headed for the University of Oregon, where she was set on studying political science and sociology. She told you she'd enter law enforcement and ascend to the highest levels of counterterrorism. You were in no position to argue.

By the end of June you were back home; by August you were walking again; and by November you were driving, although you said you made sure all your friends were off the road first.

The Horseshoe had continued to thrive despite your absence.

You couldn't play piano anymore, but you could still sing, so you wrote more songs and had your friends from Café Bazaar come over to play them.

You had to quit Redwood because you couldn't play catch, couldn't see the ball until it was 10 feet in front of you, couldn't throw batting practice because you'd lose your balance, and couldn't hit fungoes. You recommended that the young man who replaced you on an interim basis, Jeff Packman, be given the full-time job right away, and the administration honored your wishes. The father of one of your players wrote you a letter. "You saved the program," he told you. You saved the letter.

But you couldn't give up on the game, not after reveling in the joy it had brought you when you went back to it after all those lost years. You knew you could still coach and teach, so you're doing it. You're back at Redwood, volunteering with the freshmen, trying like mad to rein in those unhinged hormones -- to get these kids to learn the mental part of the game early instead of late, like you did.

Well, you're not at Redwood quite yet. Not this morning.

There's traffic on the Golden Gate Bridge and fog so thick you can't see the Headlands until you're almost on top of them. But as always, once the 101 takes you through the Waldo Tunnel, the one with the rainbow painted on it, the fog vanishes and you're greeted with the overpowering sunlight of Marin. Only a few more miles.

You park and head to the field under a sparkling sky. Today's project is a pudgy left-hander named Robbie. He's maybe 5-foot-9 and a bit absent-minded, but he's got a great arm. That's why you took him out of right field and put him on the mound.

From afar, you've seen the problem. Robbie throws hard, has great stuff for a kid his age, but he likes to nibble. He likes to come up with tricks and passive ways not to get beat instead of digging in, rearing back and coming strong with everything he has every time, knowing that he's better than that fool with the bat in his hands -- knowing that his best should be good enough.

Now you're in his face for the first time, and he doesn't seem to like it. You're testing his manhood. You're telling him that a pitcher with a power fastball who doesn't have the stones to throw it right down the middle is a wasted body on a baseball field. You're telling him that just for a moment you'd love to see him forget everything he's been taught about mechanics, pitch sequences, location or the count.

"Just grip it and throw it," you tell him. "All you need to know is that when a guy makes it to first base, you want him to turn right, not left."

Robbie thinks about it for a second and laughs. You nod your head at him, squint at the blinding sunlight and watch. He nods back.

He turns, looks at the catcher, and lets it go.