The love affair between Geof Morris and the only college hockey team south of the Mason-Dixon line began innocently enough.

Morris, an Air Force brat who bounced around four different states before moving to Alabama 14 years ago, fell in love with the Alabama-Huntsville program almost immediately when he arrived on campus in 1997.

He called games for the school's student radio station during his senior year. He graduated in 2002 with a degree in aerospace engineering and then proceeded to travel around the country, following the team for 32 of its 34 games.

Even though Morris didn't have an official tie to a UAH program, Charger hockey had become part of him.

Then the team suddenly faced a death sentence.

School administrators announced in October they could no longer justify the annual $1.5 million the program required. Once the 2011-12 season was over, a team that had produced five national championships and made Huntsville the hockey capitol of the south would be downgraded to a club team.

Morris was already three years into a fight to save UAH hockey. Starting way back in 1999, he helped organize community rallies. He created and maintained a website and Facebook page. But for what? The program Morris loved would all but vanish. Coaches would be released from their contracts and student-athletes who came from all over North America to Huntsville for a first-class education and a collegiate hockey career would be thrown into limbo.

"I was ready to give up," Morris says. "I thought we were done. But there were people who said, 'Nope, this isn't the end for us.'"

Turns out, they were right.

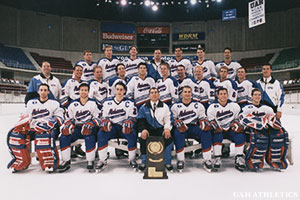

The UAH hockey program was founded in 1979 as a club team. During the next three seasons, the glorified intramural squad won three Southern Collegiate Hockey Association titles and captured the 1982 club hockey national championship. By 1984, UAH added two more national titles. Suddenly, a university known primarily for its engineering and business programs was on the map for a different reason.

Ice Hockey. In the south. In the 1980s. How?

With a population of 180,000 and the most Ph.D. degrees per capita of any place in the country, Alabama's fourth-largest city has become a high-tech destination because of its affiliation with NASA and the Redstone Arsenal Army post. That brought transplanted scientists and soldiers with northern hockey-loving roots to the land of Dixie.

"UAH hockey is the only reason why hockey is even in the area," says Jared Ross, who became the first Southern-bred hockey player to reach the NHL in 2008 after playing at UAH. "The program has brought national attention to not only the university, but also the greater area of Huntsville and even the south eastern region.

"When someone speaks of what Huntsville, Alabama, and the university has to offer, the hockey team is sure to come up."

The UAH program upgraded, first to Division II and then to Division I for four seasons. But when the Chargers found it tough to compete at the NCAA's top level and to keep pace financially, the program dropped back down to Division II.

The program's course changed again when the NCAA eliminated hockey at the Division II level, forcing the Chargers to compete at college athletics' top level.

But UAH survived and even thrived. For 10 years, UAH played as a member of College Hockey America, twice winning regular-season titles as well as winning two conference tournament championships. But that's when things slowly began to unravel.

Following the 2009 season, three teams announced plans to leave the conference. With the league depleted, plans to fold the league following the 2010 season were announced.

The choices were simple: Either find a place to play or face the difficult task of surviving as a hockey independent.

"You had to be honest with kids and you had to say, 'Listen -- there's a good possibility we won't be around in a year or two,'" says Danton Cole, who coached UAH from 2007-10. "You couldn’t go any other way with it."

Where UAH would play or even if UAH would play cut significantly into the talent pool Cole and his successor, Chris Luongo, faced. Cole, who now coaches the 18-U team for USA Hockey's National Development Program in Michigan, says the fact UAH didn't have a conference became an obstacle that became tough to clear.

"For the kids that have a lot of choices (of where to play), that's a black mark," Cole says. "That's something that you probably can't overcome with 80 to 90 percent of the kids."

In Cole's final season, UAH won the final CAA conference tournament, reaching the NCAA Tournament, where the Chargers were eliminated by eventual national runner-up Miami.

But with its conference folding, UAH had to apply for membership in the Central Collegiate Hockey Association, which boasted powerhouses like Michigan, Michigan State and Miami. The CCHA denied the Chargers' membership application, so UAH became the only Division I program to play outside the confines of a conference. With no conference ties, UAH was often at the mercy of its opponents, playing whenever and wherever it was told just to fill out its schedule. The Chargers finished their first independent season 4-26-2, playing long stretches away from Huntsville.

Last season, the Chargers were on the road for four consecutive weeks, playing in Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio before finally returning back to Huntsville. Bus trips took as long as 11 hours each way. By the end of the season only 10 of UAH's games had been played at home. Of those five series, only two were played while classes were in session. Those four games were played 5½ months apart.

By this time, the program was struggling to maintain its fan base in a city where hockey was not exactly king. "Any program where their future is unclear, your casual fans are certainly less likely to follow you," Luongo says.

Luongo hoped for better results in Year 2. But on Oct. 24, Malcolm Portera, the University of Alabama systems chancellor and interim UAH president, issued a memo to the school's faculty and students.

He cited tough economic times, saying the university was in an era when "universities must look at the value of every dollar we spend." Portera pointed to a hockey travel budget that is bigger than all of the other men's programs combined and an operations budget that cost the school three times that of all of the other men's programs.

"It has become obvious that, for the best interest of this university, our athletic department and the ice hockey program, we move the team from the Division I level back to its original classification as a club sport at the end of the 2011-2012 season," Portera wrote.

Morris was stunned.

"I never thought I would get to the point where I would see my own university kill the hockey program,” Morris says. “But that's where we got to this summer."

Luongo called his players together to break the news. At the time, UAH was 0-8-1.

"It was a sad day -- it was sad for the school and it was sad for the guys who have years remaining here," senior alternate captain Jamie Easton says. "It was just very disheartening that the school would just drop a program like that so much had been poured into."

Easton came to UAH from his hometown of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. He chose Huntsville more because of its business school, which is ranked in the Top 10 among federally funded economics and management programs. But UAH also offered Easton the change to play immediately, making the opportunity too good to pass up.

"I had the stereotypical, Alabama redneck idea in my head,” Easton said. “I knew it was going to be different. But it wasn't until I got down there that I really found out what the city was like and how knowledgeable and smart the people were."

Easton is one of two seniors on this year's Chargers’ roster. He has been among the upperclassmen asked to help hold things together once the decision to end the Division I program was announced in October.

It hasn't been easy.

The Chargers are 1-19-1 this season after being swept by Bemidji State over the weekend. In addition to being young and inexperienced, the uncertainty of the program's future has taken its toll. For freshmen like Kyle Lysaght of Marietta, Ga., it was tough not to think of leaving.

Around campus, Lysaght spoke with students about the program, asking them to back the team. The message was simple: We're here and we want to be here even if school administrators felt differently. Little did he know that Morris and the grassroots group determined to keep the program at the Division I level was gaining traction.

Morris and Huntsville resident Will Nickelson organized letter-writing campaigns to public officials. They asked supporters to remind university and community leaders what the program meant not just to the university, but also to the city.

Since the UAH program started 33 years ago, Huntsville had seen hockey become a mainstay. There were successful youth programs bursting at the seams. There was a minor league franchise that had become popular among local residents. There were adult recreational leagues. And then there were the Chargers, who had become part of the face of the university.

Morris has had opportunities to move with his career. But as attractive as the offers have been -- including one from a company in Denver -- UAH hockey kept him from leaving. So now, with the program facing extinction, Morris and his group had to fight.

The secret, Morris says, was to identify potential backers and meet with them. Morris learned the money to keep the program alive was there. All he had to do was tap into it and convince would-be donors that their investment would be worth it.

Support began to pour in. Morris, who had at times had become discouraged by the enormity of the task, began to see the chance for new life.

"It was heartening to see that there were people who cared about it as much as I did." he says. "Some people cared about it even more."

Supporters soon found an ally in new UAH President Robert Altenkirchen, who told the group he felt hockey was a unique part of the school's identity.

Supporters flooded the President's inbox with emails. Morris and others vowed that if hockey disappeared, so would the financial contributions they had made to the school since they graduated. Even Huntsville Mayor Tommy Battle got involved, as did state representative Phil Williams, who met with Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley about the program.

Over the past three years, the group has raised more than $546,000.

"It takes a lot of people pulling on a lot of oars," Morris says. "We all played our own part, but it's been really good to see everyone come together."

Hockey backers continued to visit with school officials, and following a meeting with Altenkirch on Dec. 6, they got the answer they had been waiting for:

"Members of The University of Alabama in Huntsville administration met this evening with hockey supporters, following discussions with Chancellor Malcolm Portera, and came to a consensus to work closely together to pursue institutional and community support to continue UAH hockey at the Division I level.

"Several scenarios were discussed to ensure recurring support is in place, and the two groups will continue to meet in the coming days to finalize a workable plan."

Somehow, a final push destined for nowhere resulted in a comeback no one expected. Although more details are expected to be released soon, the team that had been skating on thin ice for so long suddenly had new life.

Luongo hopes the recent turn of events will also lead to a turnaround for the Chargers. For young players like Lysaght, the decision secures their future and again restores the joy of being a student-athlete -- which Luongo says was the biggest crime committed during the entire ordeal.

The future finally appears secure at UAH, a school where fans and the program’s supporters have always looked up to their beloved Chargers. But now, it’s the players that have fans to thank -- not just for exuberant support at the rink, but for a second chance few saw coming.

It's a renaissance rarely found in this economy and in this era.

"You can’t put into words what it was like to hear that these guys met their goal and got what they wanted," says Lysaght. "They wanted to prove that hockey in Huntsville wasn’t going to go away."

Huntsville was always a place where young people came to learn about space. Then it became a place where young people could go to learn and play hockey.

Thanks to a true hockey believer and some of his friends, it's still a place where the stars align.

-- Jeff Arnold can be reached at jeffarnold24@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter @jeff_arnold24.