The story of Mark Slavin, the wrestling prodigy brutally murdered at the 1972 Summer Olympic Games, begins years before he was born -- during the Second World War ...

The Eastern Front, 1941-1943

Many thoughts crossed Grisha Czerniak's mind in the lonesome hours in the small army prison tent near Stalingrad, awaiting his death by a firing squad of his peers.

At times tears flooded his eyes, overwhelmed by the images of his two beautiful daughters he was destined never to see again. Other times, when a strange tranquility took over, he would quietly recall his father's thoughtful advice. Grisha's father had thoughtfully repeated to his son that strength was a heavenly blessing for the Jew in the difficult times that never come to an end; but these powers are to be executed in modesty and restraint, as power can be the cause of unimaginable plight.

So as an adult, Grisha would never strike a man, not even the crudest and most ignorant anti-Semites, not even the Germans he would capture beyond the enemy lines. He would powerfully strangle them, and then gently ease his grip as they acknowledged that silence would afford them the gift of life -- albeit in the cruel hands of army interrogators. He knew that death nested in the force of his fists.

This force would be executed more peacefully through public means, like the great weightlifting contests in the city of Gomel during festival times. Grisha liked the acting and would pretend to wobble under the weights. He would enjoy the laughter of the jubilant Jew-hating mob, then silence them in the blink of an eye with his decisive jerk.

So how did the angel of destruction enter his mind that night, as he returned from a week-long raid of enemy ranks?

"And where does one find a Jew if not in the kitchen?" cried out a despicable officer of the quartermaster, drunk as a peasant, as Grisha entered the dirty military kitchen to make some soup. He lost his temper, and in a single blow killed the disparaging man. Now Grisha was to be shot to death at dawn.

In his very final hours he would ponder about his beloved mother Masha-Esther and the lovingly embroidered kerchief in his pocket. She was a righteous woman of mystical powers, but these powers seemed to have deserted her in these god-forsaken times. She had told him not to part from the cloth as she believed that its owner would always return home safe from the battlefield.

Grisha was never to return the cloth to his mother. Like his father, she died of disease and hunger in Chkalov in the Ural mountains in 1942.

But when he woke up in the military hospital one morning in 1943 to see his wife Chasya's beautiful eyes, he would immediately hand it to her. He could not even smile as the pain of the metal shreds in his jaw was unbearable. But he could not think of any other reason for his life being spared but the blood-soaked hand-kerchief.

A strong hand had hurled him from his thoughts that fateful night.

"Hastened in putting the Jew to death? I hope you haven't forgotten the priest," Grisha barked at the figure he thought to be this executioner, who was accompanied with two other men. He was honestly amused. The camp was still in total darkness, and executions were strictly reserved for the crack of dawn.

"Shut up Czerniak," said the man. By God's grace, it turned out to be the commander of the division himself. He had heard of the great misfortune of one of his bravest men and rushed to the camp to bail him out. He held an apology letter carefully written by his personal secretary. All Grisha had to do was to sign and receive the bounty of life.

At first Grisha refused. He would not fight for a Russia that always discriminates against the Jew, be it the most loyal and brave man at her service. But the general was a clever and moderate man. He let Grisha curse for a while, then forced him to sign the paper.

The bounty of life turned out to be a short-term loan. He would be transferred to the ill-fated clearing units to which Stalin would condemn rebellious soldiers and officers he wished to see dead. Less than one in a dozen survived this honorable service of the motherland.

Grisha would look death in the eye time and again, his comrades dying while blessing their Messiah or cursing the Germans, Stalin or their own ill fate. But he soon came to the realization that death was not intended for him. He escaped it even in that massive explosion in Stalingrad, as the German bomb obliterated their barracks.

He would quietly smile as doctors assessed his condition and declared time and again that he would not live to see the next morning.

Minsk 1954 – Spring, 1972

With great love and affection, Chasya restored Grisha's love of life. She gave him four beautiful daughters. Though at times she was saddened by the absence of a male heir who could inherit her husband's unusual strength; Grisha did not spare a thought for this matter. Minsk of 1954 was still rebuilding itself out of the devastation left by the Germans, but he was surrounded by the elegant women who would frequent his thriving beauty salon. They would mischievously smile at him, although his eldest Anna was already working beside him.

Apart from the cream of Minsk's female beauty, the salon attracted the more courageous of Minsk's young Jewish men, who were hypnotized by Anna's splendor. Even 50 years later, when as a fragile widow she often visited Tel Aviv hospitals, elderly doctors would ask her daughters' permission to court her.

At first she seemed to have fallen for Misha Slavin, the smooth-talking son of a famous intellectual, Zalman, who once served in the provincial government as the treasurer. But she would ultimately choose Misha's younger brother Jacob, an electronics student who was more direct and sentimental in her love to her. She married at the age of 17, and within a year gave birth to a boy -- Mark.

Unlike Grisha, Chasya was far from pleased. She thought Jacob a light headed boy and envisioned Anna entering higher education and fulfilling the dreams she was deprived of by the war. Chasya did not wish her daughter the life of a teenaged housewife.

She encouraged Anna to return to work; and as she herself had just given birth to her fourth daughter, Maya, she would breastfeed both babies together. Her great desire was finally fulfilled by a boy. She was breastfeeding a male heir who was destined to own strengths even greater than his grandfather and great-grandfather.

But Anna was in love and had not intension of deserting Jacob. Beside her beauty, she had her own quietly persuasive powers, and she attributed his light-headed nature to youthful enthusiasm. Soon he would get on track, complete his studies, and receive a good job at the Gorizont plant, manufacturer of Eastern Europe's finest televisions and radio sets.

In a more liberal post-Stalin era, the gift of electronics would cross political borders for them. They could listen to the latest music broadcasted by the BBC World Service or Voice of America.

One day, a strange-talking American youngster entered the Gorizont plant. He was burning with the fever of Communist ideology. Grisha, who as a military hero was forced to join the party, was dismissive of this rhetoric, but Jacob took a liking to the young American. He may have been strange, but he had 45 rpm records of the emerging American singer Elvis Presley. The American's name was Lee. He would leave Minsk within a few months, and when he returned to his country, he would eventually murder John F. Kennedy in Dallas.

Visitors to the family home who saw little Mark dance to the tunes of Heartbreak Hotel or Love me Tender, or gaze with great amusement at paintings, could not imagine the mythical powers resting in him -- but the signs were soon to emerge.

They lived in the adjacent house to his grandparents, and one day he and his young aunt Maya were left to play with his other aunt Masha, only six years his elder, in charge. A snowstorm was raging outside when Masha noticed that Mark had disappeared. But as her fears were mounting, she suddenly heard a childish giggle outside. She ran to the window and saw her young nephew joyfully rolling around in the fresh snow.

As his athletic prowess became evident, his young aunts secretly wished he would choose to become a tennis player. Tennis seemed an intelligent, elegant sport that will complement their little Renaissance man.

By the end of elementary school, he would play beautifully on his big red accordion, listen to Tchaikovsky, read Pushkin and Majkowski. He would paint Minsk's beautiful forested landscape. But most of all, Masha loved to hear Mark sing Jewish and Russian folk-songs and, of course, their beloved Elvis.

Meanwhile, outside the home it was a darker world where Mark exercised his enormous powers. As happy and carefree and good-hearted he was among his loved ones, he would never fail to retaliate for the anti-Semitic taunts directed at him or his young brother Elik. Weeks and months would pass by with Elik and Mark daily engaging in brawls, and Mark never tired from teaching these ignorant thugs bitter lessons. They would learn to appreciate the strength of this smiling Jew.

Back at home the amazement at his power continued to grow. At 12, he could lift Jacob with both hands. This physical strength would not go unnoticed by sporting recruiters of the intensive Soviet Olympic sports system. At 14, he was sent to the Palace of Sports -- a school for the elite of Belarus' sporting talent.

Initially, he was not sure of his choice of sport. For a while he leaned towards boxing -- it seemed quite natural. Jewish Belarus had produced a line of illustrious boxing champions: War hero Vladimir Kogan was a seven-time champion of the Soviet Republic, Anatol Skladnovsky had won the Soviets a bout in a lucrative duel against the Americans, Vladimir Botvinik had won the Spartak Games, and Boris Prophas was a 3-time champion of the Republic.

One day, Grisha and Chasya were drinking tea in their living room, enjoying the company of their young grandchild David. Suddenly the house’s walls began to shake. It was strange as the weather outside was actually pleasant. They discovered the cause in Mark's room. He had stripped the seat-padding from an old deserted car and prepared a makeshift boxing bag which he hung on his wall. He was not aware that his fists now seemed to rock the house to its foundations.

Eventually, he chose Greco-Roman wrestling. It was the classical elements of the sport that truly captured his love, as well as the need to execute power with preciseness and tactical thought. He liked the drawings he saw in the old wrestling books he began to collect. Here, too, Minsk's Jewish community had produced sources of inspiration. In 1960, Oleg Kravayev was crowned Olympic Champion in Rome. Michael Mirsky was a 25-time champion of the USSR in several martial arts and author of 17 wrestling books. He would coach Mark into a great champion.

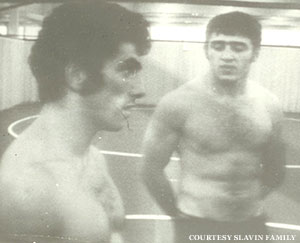

There is one definite theme that repeats itself in all the clear or vague recollections of people who remember the great Mark Slavin in his wrestling years in Minsk. No one remembers a child. No one remembers a teenager. The boy, who at the age of 12 had the physical strength of a grown man, matured in wisdom and thoughtfulness and purpose way beyond his years.

In a family dominated by women, he became a leader. Chopping firewood with a great axe in autumn, speaking passionately and decisively against the institutional anti-Semitism they confronted in the tense political climate of the early 1970s, drawing dozens of friends and admirers to the family home and leading them in song with his red accordion.

Today, when Mark's sister, Olga, takes his clothes out of the closet every now and then to air them out a little, she is often surprised. They seem so small. In reality, Mark was a wrestler in the 74kg division -- 163 pounds -- but she remembers him as a giant. Ten years her elder, he would not once hold her hand but would always carry her on his broad soldiers. With him she would encounter the world not from street-level, but riding a mythical titan.

From the perspective of time, she can see things she could not have appreciated as a child. She once found an old psychology book among his belongings. What did a carefree superstar athlete of the Soviet Republic find in what was considered a suspiciously bourgeois field?

Few of his loved ones ever saw him compete. In his free afternoons, Elik would visit the Sports Palace. Soaking in pride, he heard the spontaneous whistles and cheers as Mark's speed and power amazed all spectators. They marveled at the ease with which he would grind opponents -- fellow students at first, then soon established Olympic-level competitors.

But his family could never attend the big competitions. These were held in faraway parts of the giant republic. Glory came in the form of an excited phone call, a radio bulletin or a newspaper headline. Like in 1971, when Mark returned from the Ukraine as Junior champion of the Republic. Or later, when he achieved an improbable draw with Viktor Igumenov, the reigning six-time world champion.

In his years at the Sports Palace, Mark developed an abhorrence of Soviet-Russian culture. He grew closer to his paternal grandfather Zalman, who would tell him of the Hebrew classes he had taught before the war, classes that now were forbidden. Zalman talked about his sadness on not being able to hold a Bar Mitzvah for his grandchildren.

Mark began to acknowledge that anti-Semitism was deep-rooted even in the supposedly open and democratic world of sport. A dramatic decision began building up inside him. Soon after his 18th birthday, he filed a request for a visa to Israel. He would not represent the Soviet Union. He would relinquish the elite status the Soviet Union had afforded him. He would refuse an apartment, scholarship, international travel and handsome salary offered to him if he was to cancel his visa request. This was tantamount to treason.

He intended to emigrate alone, but his decision inspired the family. Grandmother Chasya, for whom he was always a son, decided the whole family would join him. They were a group of 17 people on a cold morning at Minsk's central railway station, boarding a train to Vienna.

KGB officers patrolled the station, taking note of people coming to bid the traitor farewell. Nevertheless, several of Minsk's Jewish athletes and other friends defied the danger and came. Michael Mirsky brought his champion student an oil-painting. They were to leave an entire life behind. Olga was allowed but one small rubber doll to take with her.

Mark hardly spoke through the entire journey as the train crossed Poland and Czechoslovakia en route to the West. He sat quietly next to Elik. His aunt Masha remembers him shining, as if an aura surrounded him.

Tel Aviv-Munich 1972

On his first day in Israel, Mark went to the "Hapoel Tel Aviv" Wrestling division. It was the only Israeli wrestling club he had heard of. He told the club officials he was the Junior Champion of the USSR.

Quick bouts were organized to verify his extraordinary pedigree. He hardly broke a sweat in defeating experienced wrestlers from any weight division. As a final test, an Olympic medalist from France, Daniel Robin, was flown into Israel. Mark beat him with ease.

As he boarded the plane to the Olympics, he promised Elik to bring home a medal -- to tear it away from the Soviets.

On 25th August 1972, Mark Slavin wrote a letter from Munich:

Father, Mother, Granny, Elik, Ola and my two aunts. I hope you have a happy new year and that you will all be happy and healthy.

I am writing to you from the Olympic village. It is a place of the future. I cannot stop staring at it. They tell us that in the future, in 100-150 years, they will build cities like this -- with cars only traveling underground.

We arrived safely. We had a tour of Switzerland before we arrived that was very beautiful. We were given a luxurious room. They bought us Adidas shoes and tracksuits, half price, I think I will buy for father and Elik.

Athletes from many countries are living with us. I exchanged pins with them. Only the Soviet Union hasn't arrived. When they come I will meet everyone.

In the meantime I am training once a day.

I received 300 Deutschmarks but I won't waste it on nonsense. I wrote grandpa Zalman a letter. I didn't say anything. Like a Soviet athlete writing to his grandfather.

Today we will go to the synagogue to pray. I will pray for all the Jews to get to Israel and fulfill their dream, like I did. I pray for uncles Isa and Misha to emigrate too;though I understand there is no news on their case.

Regards to all,

Mark

Goodbye, 1972

In the days leading up to competition, Mark trained with Bert Kops, a Dutch wrestler in the 90 kg division. They were also training with Petros Galaktopoulos, the eventual silver medalist in Mark's division. Kops had never heard of Mark Slavin and was surprised that the almost anonymous Israel had such a wrestler. He later learned he was a Soviet champion and now it made more sense to him. They never actually spoke as they had no common language.

He felt this was a wrestler with power and purpose from another sphere, way superior even to Galaktopoulos -- a wrestler of considerable fame. He sensed the resolve of an athlete about to do something big. He was convinced he was going to win a medal -- very possibly the gold.

On the morning of September 5, 1972, Anna and Jacob went to the bank. It was the day Mark was due to compete at the Olympics. They hardly knew a word of Hebrew, but Anna noticed a sports paper at the newsstand outside the bank.

She identified a large photo of Moshe Weinberg, the wrestling coach. It seemed odd. Why would the newspaper carry the photo of the coach and not the athlete? She knew one of the bank clerks that spoke Yiddish. She asked him why.

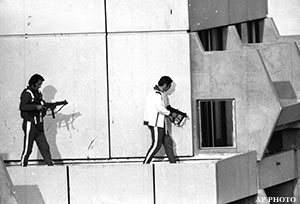

In the early hours of September 5th, 1972, a group of eight terrorists from the Palestinian "Black September" faction entered 31 Connollystrasse -- the Israeli team residence at the Olympic Village. They killed two team members, including Mark's coach, Moshe Weinberg, and took nine hostages, Mark Slavin among them.

An 18-hour standoff was followed by a failed ambush and rescue attempt by the German police at a local air base. All of the hostages died.

In years to come, the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad and the Israeli Defense Force special units hunted down and killed dozens of those involved in planning and carrying out the massacre. The operations included one mistaken assassination of a Moroccan waiter in Norway.

The Olympic Games in Munich commenced on the 6th of September following a memorial service at the Olympic Stadium. A relative of one of the victims died of a heart attack during the service.

A Family's Pain

When Mark Slavin died in Munich, the family's extraordinary strength that saw them through hardship from Stalingrad to Israel was lost as well. At his funeral, Chasya pointed at a small strip of land and asked to be buried there, beside the child she had breastfed. Within two years, she is granted her wish; she died at the age of 59.

Anna and Jacob became sick, heartbroken people for the rest of their days. They could not find the courage to send their own children on school trips. Anna would suffer anxiety attacks even to the sound of Arabic from the television. She imagined the last sounds of her son's life.

When Elik went to war in Lebanon with the IDF, he received the kerchief that had saved his grandfather in Stalingrad. He survived the war. Somehow, despite serving in a commando unit, danger was always five minutes or a few kilometers away. He often wondered if the cloth should have gone to Munich with Mark. But how were they to know?

Like his father, Elik believes Mark never kissed a girl. A few years after his death, Jacob candidly told a BBC journalist that his son died a virgin. Elik knows his brother showed interest in a girl he had met at the Wingate Sports Institute north of Tel Aviv, intending to court her after the Games.

But Olga saw a woman at the memorial services. She came year after year. Brown haired. Nice. She wants to believe this was Mark's lover, but she could never ask her parents. Never enquire. They would not talk.

In Minsk, Aunt Genia could not mourn in public. The house was still under KGB surveillance. She went visiting family friends to listen to their stories about a boy who at 18 was a hero to Minsk's Jewish Community. During one of these visits, her son David was playing with fire, got injured and hospitalized. The foreign press mistakenly reported it was a result of anti-Semitic attacks.

In Zhlobin, the Czerniak and Slavin ancestral hometown, Zalman Slavin received the letter his grandson promised to write him from Munich. The once large Jewish community had diminished to only 500 people after the Holocaust. The fact that one of the dead Olympians had ties to the town was not published, for fear of anti-Semitic attacks. The town synagogue had long been confiscated by the authorities and Zalman organized prayers at a friend's home.

Mika Slavin

Mika is the loving sister who was always condemned not to ever know her beloved brother. In 1974, Anna and Jacob found the willpower to bring another child into the world. She knows there is no alternative history where she could have known him. In a world where he does not die, she isn't born. In the world she came into, he was never there. In first grade, the teacher told the class that among them is a special girl that had a very special brother.

His existence was the old cabinet that stood by the door, storing his belongings, which she was forbidden to open. Her brother lived in the eyes of the people that looked at her. Mark Slavin had a soft, almost feminine face. The resemblance is striking.

"For years I simply thought I was him," she says. "When I played music, people would say I'm like Mark. I wanted to be myself, so I stopped. For a while I did well in sports. But again people saw Mark so I quit. I blamed myself. I thought it was all my fault, that I was the reason Mark was dead and all the family was suffering."

Even when she turned 18, memories would not loosen their grip. Uncle Isa, Jacob's oldest brother, finally emigrated. When they met at the airport, he blurted out in confusion, "Mark my child!" and ran up to hug her. He quickly recovered his thoughts and apologized.

But every few months they would open the cabinet and she would be overcome by deep feelings of sisterly love. Most of all she liked his personal things. The wallet. The spectacles. The little dolls he bought Olga in Munich. The little bottles of spirits he bought for his father that were now slowly evaporating. The prizes and medals meant less to her.

In her search for her brother, Mika reached a mysterious apartment, and a weak-boned fortune teller with a high-pitched voice. Her dwellings were strange. Some painting of great Kabbalistic rabbis hung on the pink walls.

Mika asked for Mark but the woman could not find him.

"I want my brother," Mika repeated again and again. The woman asked again for his birth date -- January 31st, 1954.

"Maybe he died of an unnatural cause," said the woman.

"Yes, Yes," Mika replied. The woman asked for his date of death. She told her: September 6th, 1972.

"I see a young handsome man. A bachelor. A wrestler," the woman suddenly said. Her voice suddenly changed.

Someone else spoke from her mouth.

"Are you with papa," she asked.

"No. I'm in a different sphere. With the soldiers that died. Papa is elsewhere."

The voice from inside the woman went on:

"They were egoistic. The Germans. They will not take responsibility. But you will win the court case. And get the money. It will be too late for Mama.

"You didn't know me. But I want you to know that the stories were true. And I'm so happy you are my sister. I'm so sorry I cannot hug you. But look after yourself. I will return. In 15 years I will return."

Mika believes he will return.

"I do," she says. "But he won't return to us. He will come back somewhere in this world."

Then she continues: "I guess you think I am crazy. But I just can't live this life without the feeling that Mark is with me."

-- Ronen Dorfan is a journalist with Israel Hayom. He can be reached at ronen@ronendorfan.com. A version of this story has appeared previously in Hebrew.