David Eckstein is up next, and he’s filled with familiar anticipation and butterflies. He’s been on-deck thousands of times as a major league ballplayer, a few steps from home plate, waiting his turn. But this is different. He’s ready to donate a kidney because that’s what people with his last name do.

He’s been preparing most of his life, and, as with an at-bat, he’s watched others experience it first. Only three months ago, David’s brother Rick, the hitting coach for the Washington Nationals, donated a kidney to their oldest brother, Ken. An entire scorecard of Ecksteins, in fact, has either needed or donated kidneys.

Everybody goes under the knife. The current Eckstein box score: Five kidney transplants with six more anticipated. Two family members and a close friend have donated kidneys.

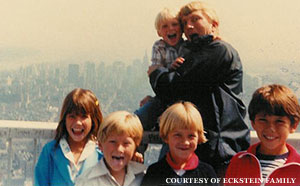

Until now, David (on the right in photo with Rick, Ken and Whitey) has been left out because of a career that has earned him nearly $20 million. Fans love him. Baseball people respect him. Numbers crunchers deride him. His family spares him.

A 10-year major league veteran and most valuable player of the 2006 World Series, David might never have made it to the big leagues without his family’s collective inability to filter toxins and waste products from their blood. One of the smallest players in baseball at 5-feet-7, 175 pounds, he is an overachiever known for a tireless work ethic and relentlessly positive attitude.

“Everything my family went through gave me a life lesson at an early age that a game is just a game, it’s not life-or-death,” he says. “But along with that, it taught me to never take a day for granted.”

Currently he’s out of work. The San Diego Padres, who he helped to within one game of the playoffs in 2010 by not making a single error at second base, declined to re-sign him. He’s had several offers, but turned them down because he felt the opportunity wasn’t right. His dad says he’s retired. Rick says he’s not. Even if he plays again, David is an Eckstein first, a ballplayer second.

“I’m looking forward to the transplant,” he says. “I consider it a privilege. I knew at some point it would be my turn.”

Transplanted kidneys usually begin to fail after 10 to 20 years, depending on the age of the donor, and that’s why Ken, whose first transplant came in 1991, needed a second one in December. A blood test established that Rick, like Ken, was O-positive, and no questions asked, Rick gave up a kidney.

Now one of their sisters and several nieces and nephews are showing signs of renal failure.

That puts David in the Eckstein on-deck circle.

Herbert “Whitey” Eckstein was 17 when he received a double dose of deflating news after taking a physical exam in 1962. First, he couldn’t accept an appointment to West Point. Second, the reason he couldn’t was that he had a kidney ailment, diagnosed because his urine was full of protein.

This was before dialysis machines were prevalent and before transplants were widely accepted. “You won’t make it past 40,” the doctor told him.

Whitey’s parents had emigrated from Germany and settled in New York City. Tough and stoic, he plowed ahead as if he’d live to be 100. He married Pat, an Italian girl from New Jersey, and they moved to Sanford, Fla., took jobs as teachers and had five children: Ken, Christine, Susan, Rick and David.

The thought never occurred that Whitey’s looming kidney problem could be passed to the kids. Not much was known about kidney disease until the 1970s. The Ecksteins had no knowledge that Whitey’s disease had a genetic component until Susan became deathly ill at age 16 in 1988.

All the children were tested and Ken and Christine as well as Susan were diagnosed with glomerulonephritis, characterized by inflammation in both kidneys. David (pictured at right with Whitey at the Baseball Hall of Fame) and Rick, in their early teens, learned they’d been spared the genetic hiccup. The other three would need transplants within a year or two.

Whitey told them do what he said, not as he did.

“I was a pouter,” he says. “You can’t get ahead pouting. I told my kids, never pout.”

The family got busy finding healthy kidneys. Pat was the first to donate, and Susan was the recipient on Nov. 29, 1988. Ken and Christine received transplants from recently deceased donors two years later. Whitey is alive because Ken’s best friend from college volunteered as a donor in 2005. Susan and Christine have six children between them, and four have been diagnosed with kidney disease.

Doctors say the sheer volume of transplants in the Eckstein family is extremely rare. Perhaps even more remarkable is the family’s upbeat approach in the face of a devastating and potentially deadly disease.

“The Ecksteins don’t see this as a hindrance or a curse, they see it as a way to bring the family together,” says Dr. Michael Angelis, Chief Surgical Director of Transplant Services at Florida Hospital in Orlando. Dr. Angelis performed the transplant surgeries for Ken in 2010 and Whitey in 2005.

Dr. Angelis says Whitey beat the odds by not needing a transplant until his late 50s. He’d been on a donor list for more than two years, waiting for a deceased donor with O-positive blood, when he lost consciousness during a phone call to David, who was boarding a plane to Detroit to play in the 2005 All-Star Game.

“I can't breathe,” Whitey said to his son before collapsing. “Here's your mother.”

By the time David reached Detroit his father had been stabilized in intensive care, but he needed a kidney, and fast. Lori Vaughan, a Tampa attorney who’d attended law school with Ken and developed a close friendship with the entire family, took a blood test and it came up O-positive. Within hours she was in surgery.

“She’s part of the family,” Rick says. “Dad is back to living a full life and Lori had everything to do with that.”

Whitey spent his career teaching and coaching golf at Seminole High School in Sanford, a town of 40,000 northeast of Orlando where he and Pat settled to raise their family. Pat was a grade-school teacher. Whitey has long been a pillar of the community, serving as a Seminole County Commissioner for two decades. The local youth baseball complex is named after him.

When Whitey and Pat want to speak to their daughter Christine, they walk across the street, where she lives with her husband and four children. When they want to see Susan, they walk around the block, where she lives with her husband and two children. The Ecksteins share kidneys, and they share a neighborhood.

During the baseball offseason, Rick lives in the original family duplex where Whitey and Pat raised the kids. David has a house in Sanford that he shares with his wife, actress Ashley Drane. Ken isn’t far away in Tampa.

Family is what matters to Whitey and Pat, and they raised their children with an urgency only a couple who believe time is short could fully appreciate. Whitey kept it to himself, but every night when he laid his head down, he heard that doctor’s words: “You won’t make it past 40.”

“Nothing was carefree, nothing was casual,” Pat says. “Everything was toe-the-line. Make every day count. He lived his whole life waiting to die.”

Rick’s admiration for the selflessness of Lori Vaughan rekindled a desire he’d felt since his siblings had transplants while he was a healthy teenager, spending his days in the Florida sun playing golf and baseball. He yearned to take part in the Eckstein rite of passage, to make his parents and siblings proud. But his career as a coach, like David’s as a player, required physical exertion, and the family asked him not to take the risk yet, that his time would come.

Ken was back on dialysis last year because his first transplanted kidney was dying, and it weighed on Rick, who was in his second year in his dream job as the hitting coach for the Washington Nationals.

“I remember waking up one morning and knowing I was going to donate to my brother,” Rick says. “I can’t explain it. I just knew.”

When he got to the ballpark that day last September, he had the Nationals’ trainer give him a blood test. His parents had been under the impression Rick was B-positive, but the test came back O-positive -- a match for Ken.

Although advances in transplant technology allow a patient to accept a kidney from a donor with a different blood type, the process is much easier if the types match, Dr. Angelis says.

Rick called Christine, who had been caring for Ken, to let her know he was O-positive. As had happened so many times with the Ecksteins, the offer to give triggered an outpouring of emotion, and Christine broke into tears. Ken needed Rick to convince him that he was aware of the risks, aware that his own career could be jeopardized should complications such as infection or blood clots arise.

“I wanted to know that what my heart was telling me was real,” Rick says. “The disease attacks both kidneys. So by me donating one kidney, it doesn’t increase my risk. If I was to come down with the disease, it would take both kidneys anyway.”

Rick reminded Ken that transplant surgery had come a long way. Their mother had a scar from her shoulder to her inner thigh after donating to Susan in 1989. Dr. Angelis said the operation on Rick would be laparoscopic, requiring only a three-inch incision through his belly button.

“I’m doing it,” he told Ken.

A day after the procedure, Rick drove himself home from the hospital. He was in the gym within five days and pitching batting practice within two weeks. During spring training this year, Rick is as active as always, carrying buckets of baseballs, working with hitters and dashing from field to field at the Nationals’ Viera, Fla., complex.

“I wouldn’t say it wasn’t a big deal, but I made it not a big deal,” he says. “I used the mind-set that I was going to be fine and go to spring training and nothing was going to stop me.”

Ken, meanwhile, is good to go for another 20 years. Two kidney transplants have given him a healthy appreciation for life. He feels like he has cosmic permission to do what he wants, rather than what others expect him to do. Sure, he’s an attorney. Yes, he has a real estate license and a master’s degree in travel and tourism.

Yet with Rick’s kidney efficiently sifting the waste from more than 100 gallons of his blood a day, Ken is doing something he’d dreamed of doing for years – he’s writing a play.

The glass-half-full, no whiners allowed philosophy that permeates the Ecksteins got its start late in 1988 when Susan began feeling sluggish and moody. She was 16 and her mother wasn’t sure if the odd behavior was hormonal, a teenage phase. Susan resisted seeing a doctor even though her weight had dropped to 70 pounds.

Pat took Susan shopping for shoes one day. The next day Susan went to her mom and said he wanted to take her up on the doctor appointment. “Last night I couldn’t breath,” she said. “I had to sleep in the recliner.”

The diagnosis was kidney failure. Susan needed dialysis immediately. “The doctor told us she was a walking dead person,” Pat says. “I was given information about her health that I didn’t comprehend. Was she going to die? I began to cry and the doctor said she wouldn’t die and to stop crying, that Susan needed our strength. I never cried again.”

Pat walked into her daughter’s room with a big smile. “Let’s get started, we’re going to learn to do our own dialysis,” she said. Susan had inherited her mother’s tenacity in as much abundance as her father’s kidney ailment, and soon she was making college plans. “This was not going to be a tragedy, it was going to be a success story,” Susan says. “Get it done and life goes on.”

Once Susan’s health stabilized, the doctor mentioned a transplant, a shocking concept to the Ecksteins. “The only time I’d heard that word was in a Frankenstein movie,” Pat says. By the end of the day, Pat was onboard. Their B-positive blood types matched, Pat passed psychological and physical exams, and a family tradition was born.

The operation, called an open nephrectomy, was major. Susan, like anyone receiving a transplant, had her immune system suppressed by drugs so that her body wouldn’t reject her mother’s kidney. From the distance of 22 years, Pat describes her experience as “being literally cut in half.”

None of which dissuaded the Ecksteins from continuing to aggressively recognize and confront the disease at every turn. And to never allow it to impede reaching their goals. Susan earned a master’s degree, worked as an academic advisor at two universities and currently is a first-grade teacher at the same Sanford school where Pat taught for decades.

“Susan is the hero of the family, the silent leader,” Pat says.

Christine and Ken, both away at college, soon began to experience symptoms. One day while riding her bicycle to class, Christine had to stop because she felt so weak and tired. Whitey and Pat insisted they stay in school. “Don’t feel sorry for yourselves,” Pat told them.

They had catheters implanted in their abdomens, so that instead of traveling to a dialysis center several times a week, they could treat themselves. Less than two years later, Christine and Ken received kidney transplants from deceased donors. A few years after that, both graduated from law school.

Winning genetic roulette didn’t exactly thrill David and Rick Eckstein. They excelled in high school sports and became baseball teammates at the University of Florida, but their siblings’ tough luck tugged at them from Sanford.

“To be able to play sports and do the things we wanted to do, it gave us a different perspective,” Rick says. “A lot of my friends were thinking about parties. I was worried about whether my brother and sisters were going to live or not.”

David went on to major league stardom. Despite his small stature, he became the starting shortstop for the Los Angeles Angels in 2001 and finished fourth in rookie of the year voting. A year later, with David batting leadoff and serving as a sparkplug on defense and in the clubhouse, the Angels won their only World Series title. He was in the World Series again four years later, this time with the St. Louis Cardinals, and when they won, he was chosen MVP. Since then, he’s played for the Toronto Blue Jays, Arizona Diamondbacks and Padres.

Fame gave David a platform to encourage people to become organ donors. He got involved with Donate Life in California and with Mid-America Transplant Services in St. Louis. Booths were set up throughout Busch Stadium so fans could sign up as organ donors. He wrote a children’s book called “Have Heart,” that not only chronicled his rise from a non-scholarship college player to a World Series hero, but also championed organ donations.

“In the few years I was there, St. Louis became one of the leading cities in the nation for newly registered donors,” David says. “It’s an ongoing campaign we are all excited about.”

Angelis, the Orlando transplant surgeon, said that about 18,000 kidney transplants were done in 2010 in the U.S. and that nearly 90,000 people are on a waiting list. The three-year graft survival rate is 92 percent for a patient receiving from a live donor and 82 percent for those who receive kidneys from a deceased donor.

“Not only are you giving somebody a better life, but donating also gives you something,” Rick says. “I just remember it was an overwhelming feeling, a very powerful feeling. I encourage people to become an organ donor. If you are not a donor while living, be a donor after you pass. Create a better life for somebody else.”

It would be understandable if the Ecksteins were reluctant to have children of the own. Whitey and Pat knew nothing of the genetic implications, but that isn’t true of their children. Still, Susan and Christine started families, and the kidney problems of four of their children are viewed as unfortunate, but nothing more. Susan’s husband, Fred, has been turned down because he had a melanoma removed, but Christine’s husband, Peter, expects to donate a kidney to one of his children.

“My wife and I have zero concerns about having kids,” David says. “God isn’t going to give us something we can’t handle. If it’s put upon me that one of my children has this disease, that’s what God wants.”

It’s likely that before he becomes a father, he’ll become a donor. Susan’s transplanted kidney is functioning at less than 30 percent efficiency. The oldest of his nieces and nephews with the disease is 13, and a transplant could be necessary soon.

David has been on-deck long enough. This is how Ecksteins connect, and he’s ready to touch ‘em all.

Yahoo! Sports major league baseball editor Steve Henson can be reached at henson@yahoo-inc.com. Follow him on Twitter at @HensonYahoo.