In the past 20 years no program in college basketball has been better, or more polarizing, than Duke’s. Mike Krzyzewski’s team was once an underdog, thrilling impartial observers by knocking off the sport’s establishment to win back-to-back NCAA Tournament titles in the early 1990s. Those years have long seemed ancient. Now, as Duke fans applaud the team’s consistent success, its detractors are just as quick to bemoan its overexposure on national television -- not to mention what they perceive to be a general air of smugness. Either way, Duke is the sport’s marquee draw.

In 2007, though, Duke lost in the first round of the NCAA tournament to Virginia Commonwealth University, and Krzyzewski convened his entire staff for a traditional end-of-season meeting. His agenda concerned not only basketball strategy -- with its youngest team in decades, Duke had dropped its last four games –- but also the universally gleeful response to Duke’s early demise. Duke’s coaches were accustomed to the team’s role as a Goliath, but they felt there was a difference between rooting against a college and spewing venom at college players. A gradual escalation of vitriol had peaked, convincing them that something, at long last, needed to change. At that conference, it was decided: Duke’s players needed to have more fun, and for their sake, other people needed to see them doing so.

For years, Duke had produced a recruiting pamphlet called Blue Planet. It was mostly informational, meant to entice prospects and inform boosters. But after 2007, it would transform into a full-color monthly magazine, complete with a hefty Web presence. The new site started in earnest, with rudimentary highlight packages, occasional blog posts and public-service announcements touting the team’s commitment to community service. Soon, the videos evolved in frequency (more) and formality (less).

Something strange happened: Blue Planet was a smash hit. The response was so overwhelmingly positive that last season, even Krzyzewski sat in front of a camera for a weekly question-and-answer session. This year, the program put out its first viral video, a compilation of increasingly preposterous trick shots by the senior Kyle Singler. It's been looped almost one million times on YouTube.

The unfettered access offered to Blue Planet was part of Duke’s larger plan to humanize its players, who, at least outwardly, appeared to enjoy basketball as much as a morning chemistry lecture. As a public-relations ploy, it was conventional. But it marked a departure for Duke. It was an acknowledgement that the school’s basketball prowess relied partly on sentiment, and if the strategy had any chance of succeeding, Duke needed the sort of player who could make it more than just an aspiration.

Cameron Indoor Stadium suddenly looked young in old age. This was October 2009, six months before Duke would reign atop the sport and almost 70 years after the first game in the quaint arena, no larger than a high school gymnasium. The seats in the upper bowl, once the color of an overcast morning, had been painted dark blue. The buttresses between sections were washed to look less like cement. It was only the year before that a video monitor replaced the scoreboard suspended over midcourt, and with all of the lights out, it gleamed in the dark. Even the sound blared unfamiliar, with the announcer Michael Buffer asking a capacity crowd if it was ready to rumble.

The occasion for the makeover was the basketball team’s first practice, another shift in strategy. While other elite teams appealed to their fans with a lavish, late-night event called Midnight Madness, Duke typically opened its season with a practice closed to the public. Finally, Duke had spurned the subdued tradition and joined the crowd with its version, Countdown to Craziness.

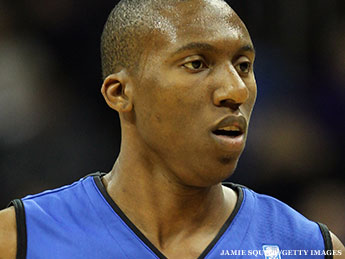

The doors to Cameron opened at 6:30 p.m., and not long afterward, Buffer called the name of a guard: “A 6-foot-2 junior from Upper Marlboro, Maryland …” Cameron filled with the tinny bass of a Jay-Z track that begins, “Allow me to reintroduce myself.”

The spotlight settled on Nolan Smith, back to the court, reveling in the attention. His eyes were covered with plastic blue shutter shades. He turned around and started to strut, shaking as he stepped. He tried, not very hard, to hide his clenched teeth with his upper lip, and the 9,314 spectators roared in equal parts delight and surprise. It had been a long time since anyone but a brash visitor had danced so proudly in this arena. No one had worn short shorts here for many years, either, yet in the slam-dunk contest later that night, Nolan slipped out of his jersey to reveal a 1980s getup underneath. After his tomahawk jam, he posed, hands on his hips, like Superman.

“It was a new beginning,” Smith said recently. “A fresh start for the program.” So much had happened since then. Duke beat North Carolina, twice, en route to the 2010 Atlantic Coast Conference crown, ACC Tournament title and, of course, the national championship. This season, as a senior, Smith is improbably Duke’s best player. He’s on track to lead the ACC in points and assists, and if he does, he would be the first ever to do so.

But all those accomplishments, like the latest basketball renaissance at Duke, depended first on a private

developmental process that took place in public. This school has churned out better scorers, better passers,

better players, better heroes and better villains, but not someone like Smith, who's injected an unexpected

and very timely charisma into Krzyzewski’s program.

It took Smith nearly two years to flash the pizzazz that earned him the nickname Showtime. He labored through a lackluster freshman season, playing just 15 minutes a game, and he almost left Duke before Krzyzewski convinced him to stay in a 30-minute phone conversation. His sophomore campaign proved more difficult. Duke climbed to No. 1 in the polls with Smith starting at point guard, but by February, the Blue Devils fizzled, and Smith found himself relegated to the bench. Three games after his demotion, he bounded into a blind screen and crashed to the floor with a concussion.

At around this time, with Nolan recovering from dizziness, headaches and a general aversion to bright lights and loud noises, Krzyzewski pulled him aside for a conversation that changed the tenor of his career. ESPN had just published a long story about his relationship with his father, Derek, who died of a heart attack in 1996, when Nolan was eight. Derek had been a fan favorite at Louisville, where he won a national title in 1980 -- he’s even credited with popularizing the high five -– and in the photos that accompany the 7,000-word piece, the physical similarities between the two are striking.

“Oh, man, this kid’s going to be an emotional wreck,” Krzyzewski recalls thinking after the story’s publication. He called Smith and asked him to come to his office to chat about it.

"No, Coach," Smith said. "I feel great about it."

"It was almost a relief that someone else could tell the story," Krzyzewski says. "He was proud of the story, and it was a burden that was lifted from him. Really, it was a huge event.”

Not long afterward, Krzyzewski sought out the sophomore with some advice. “Just be you,” he told him.

In college, Smith had tried to fit himself into the mold of a serious-seeming, pass-first point guard. But in high school, at the basketball factory Oak Hill Academy, Nolan found his niche as an aggressive, carefree combo guard, comfortable curling off a screen or isolating himself at the top of the key. That had never been his role at Duke. After his chat with Krzyzewski, he reverted back to his natural position. Jon Scheyer took over the point-guard duties and bumped him off the ball, relieving him of all its pressures. The Blue Devils won the ACC Tournament, and though they lost in the Sweet 16, when Nolan was hampered by a flu that he didn't reveal to the public, Duke had finally found a permanent fix. "That's when Coach K realized who I was going to be as a player," Nolan says. "We both realized it at the same time."

One day last week, I met Nolan for lunch at the sort of eatery germane to a college campus, where he might share an outdoor table with four people he had never met. He walked up to the restaurant wearing a long black jacket, hood down, and a fitted Washington Nationals cap, high enough on his forehead so that it didn’t obstruct his eyes.

Then it took him three minutes to make it 50 feet. Another student approached him, fumbling in his pocket and grasping for an iPhone. He held it out in front of them with his left hand, as if they were a couple in Pisa. Nolan asked to see the photo -- they squinted their eyes to approve -- and the kid took a few more chatty steps with Nolan before moseying off the other way. Wonderful! Time to eat. Nolan was interrupted again, this time by a well-wishing employee at the hot-dog cart across the way, who accompanied him to the glass door. Finally! Let's chow down. But just as we took our place in line, there was the student from the walkway, again, dressed in a white T-shirt with the words Duke Basketball emblazoned over his heart. "This looks stupid," he confessed as he handed me the phone to snap an identical photograph.

When I relayed the interaction to him, Krzyzewski acted as if he had just seen a similar encounter. "He's had more outward fun than any player we've had," he said, "and he's touched, in a very personal way, more people than anyone who's played here."

Krzyzewski was in his office, wrapping up a media blitz that might have made his mentor, Bob Knight, hurl a chair across a gym. His suite was messy with plaques, posters and trophies scattered on the floor, while a potted plant grew on his desk. In ash-gray fleece sweatpants, the coach was dressed for practice, and already he was 15 minutes behind schedule. Yet here he was, lounging in an upholstered chair, explaining why he refers to his All-American as a modern-day Pied Piper.

"He brings joy into people's lives, and that's a hell of an attribute," he said, before catching himself. He elaborated by poking fun at the description. "It's, like, 'What do you do?'" he asked, acting as his own interrogator.

Then Krzyzewski, who will soon own more wins than anyone who’s ever coached college basketball, sheepishly raised his hand, smirking like a grade-school student. “Oh,” he deadpanned. “I bring joy!”

In the summer of 2009, after the position switch but before he emerged as an All-American, Smith reserved the name @NdotSmitty on Twitter. Duke was still committed to a lighter atmosphere, and after Krzyzewski coached a collection of NBA players to the gold medal at the 2008 Olympics, the staff believed even more in this ethos. But Twitter, a medium that allows anyone to publish on a whim, tested the philosophy. Even now, some two years later, universities are banning their players from social networks. Duke never did.

Smith tweeted almost 8,500 times, and his tweets have ranged from absurd ("The wicked witch of the west still scares me!!") to honest (“This week is about Defense and Papers! Lol! Do both of these to best of my abilities and it will be a great week!”) to resilient ("Today is a new day! And guess what I'm built to win! I'm about to have a great day!"). He even proclaimed in October, on Twitter: "I'm about to change my name to Ndotsmitty that will be on the back of my jersey!! Lol that's all people call me now!"

Before long, as a junior, he was carrying a digital video recorder around campus to film his typical Saturday for Blue Planet’s website: Driving on Towerview Road to Cameron; asking Ryan Kelly to name his favorite teammate (Smith, naturally); walking through the aisle of the local Super Target to buy Scooby-Doo fruit snacks; singing in the car to "Ain't No Mountain High Enough"; challenging a student to a game of H-O-R-S-E in a municipal gym.

Few people outside the team’s tight circle had seen a Duke player act so candidly, and pretty soon, everyone else saw a transformed Smith on the court. Starting with Countdown to Craziness, the event that kicked off his junior season, he looked looser and smiled more. He was attacking the basket, warding off defenders in the half court and draining his long-range shots, all with a certain levity. He was playing like he tweeted.

He averaged 17.4 points per game and rounded out a triumvirate, with Scheyer and Singler, that was the most potent in the nation. His 3-point clip surged to 39 percent, and as adept as he was shooting, his ability to drive in the lane was even more vital. His regular season peaked when Duke's did, at home in March against North Carolina, in the most lopsided home win in the rivalry's history. He poured in 20 points, including a ferocious dunk off a hesitation dribble in the first half. In the game’s waning minutes, he lobbed an exclamatory alley-oop that all but ignited a celebratory bonfire, which he dutifully attended.

In the NCAA Tournament's Elite Eight, he posted a then-career-high 29 points to propel Duke to its first Final Four since 2004. The dagger was a three-pointer that he attempted inches away from Krzyzewski, standing on the sideline. (They slapped hands as soon as the ball swished, even as Nolan backpedaled to play defense.) More people started to follow him on Twitter, and instead of holing up in a hotel room, he tweeted more than ever. The Blue Devils then throttled West Virginia in the Final Four with basketball that was simultaneously pretty and perfect, and they beat Butler two days later in one of the sport's classic championship games.

That evening, with scraps of confetti still dotting the hardwood, Smith walked back out to the court. A national championship cap rested sideways on his head. He didn't need to search long to find what he was looking for: a logo emblemizing the 1980 Final Four in Indianapolis. This was the same city where his father, Derek, had won his NCAA title. Carrying his new trophy in one arm, Nolan crouched and pointed down, right at the '80 etched in paint. A Duke staffer snapped a photograph and, the next afternoon, uploaded it online for anyone to admire.

Nolan considered bolting early for the NBA Draft –- he was projected to be a second-round selection, at best -- but he and his co-captain, Singler, returned for their senior season to defend their title. His decision wasn’t a surprise. Even Nolan’s mother, Monica Malone, cops to enjoying college hoops more than she does the NBA, and when I joked that her opinion might change next year, she snapped back quickly: "The NBA's a job for Nolan! This is fun."

Somehow the fun has continued, even with the burden of repeating. “Nolan’s able to develop a lighter atmosphere about winning,” Krzyzewski says, “which doesn't wear a team out” He’s carried Duke so far, averaging 21 points and 5.6 assists per game as a fringe national player of the year candidate, and his charm is just as transparent as it was last March. Smith receives the most fan mail of any player -- around the holidays, he tweeted his address for people who wanted autographs -- and every so often, he rides up to the fifth floor of the basketball office to collect his haul, even though the program’s administrative assistants offer to sift through the letters for him.

The new attitude is apparent on the court, too. It was only in 2006, after all, that the team’s road losses were celebrated with court storms so raucous that Krzyzewski pulled his starters before the buzzer out of caution.

"Teams don't come at us like that," Smith says.

What about fans?

"It's a lot less hostile now. They still want to beat Duke, but it's not the same."

The head coach mostly agreed. "There are some people who perceive the program to be the best thing that's happened to this planet, and there are some who see it as the evil empire," Krzyzewski says. "But other players on other teams, they all like Nolan. He's one of the really great people people that we've had in our program, and in that way, he's touched people in a different way. Maybe those people who want to look at something negative, they can see the program in different light. And the people who do support the program, and do love it, they also can see the program in a different light."

Two days later, Smith ambled out to the court, empty and serene, at 5:55 p.m. for an 8 p.m. tip. He was the first player in Cameron, and I decided then that I would track this game simply by observing him. I couldn’t have picked a better night to do so. It was a marvelous display -- spectacular, Krzyzewski said afterward --with Smith racking up 28 points and eight assists in a performance that probably cemented him, even in January, as the ACC’s player of the year. Watching him was like seeing a game through a single lens with panoramic capabilities.

It was a fairly lopsided matchup, another meaningless rout for Duke, and the one moment that lingered with me long after Cameron cleared out had nothing to do with basketball. Right after a quick, late timeout, when Smith knew he wouldn’t be in for much longer, he was matching strides down the floor with his defensive assignment. The two guards were almost bumping into each other, they were so close, and yet they weren’t chatting, only shuffling their feet in step. The official scorer was ready to sound the horn, the referee poised to blow his whistle; in this lull lurked a strange silence. Walking the way of the four banners in the rafters, Smith glanced to his left, one last time, like an instinct. He paused. His eyes widened, ever so slightly and -- yes sir! -- there it was: The sly hint of a smile.