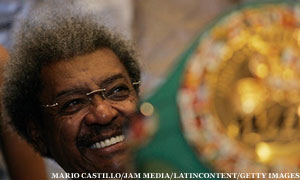

The greatest salesman in sports has teased his hair as high as its nearly 80-year-old roots will allow. He’s standing in a television green room, waving two small American flags and playfully eyeballing a woman who approached and asked how he, “Mr. King,” was doing?

“Better now that I’ve seen you,” Don King says.

She giggles. Seventy-nine years old and King is still smooth. Women are called “darling” or “beautiful” or both. On occasion, they are declared so pretty they deserve free tickets to the fights. He’s quick to offer a hug and slow to let go. No one finds him inappropriate. They find him to be exactly what Don King is supposed to be. Can I get a picture to put on Facebook, they ask. Facebook? Whatever. Of course, you beautiful darling.

Don King has killed two men, one with his bare hands. He’s served time in prison, been sued, condemned and criticized. He’s been called the epitome of an American con man. He’s also been hailed as the embodiment of the American Dream, and not just by himself. He’s promoted over 600 championship fights, made millions for many and raised countless piles of cash for charity. For all his obvious self-promotion, he’s stood tall for just causes big and small.

He’s been courted by presidents (“I delivered Ohio and Florida for George W. Bush”), named a peace ambassador to the Middle East, and continues to overcome setbacks that would crush most mortals because of a simple axiom.

A salesman is a salesman and they don’t come better than Don King, the old “numbers brother” from the east side of Cleveland, who’s been able to maintain his old cut-throat gangster instincts while selling the world on a loveable, huggable persona so harmless younger women still swoon. Whatever he’s done wrong, the public has apparently forgiven. Or forgotten.

King lives in a mansion in Florida complete with tropical temperatures and a view of the ocean. He has more money than even he can spend. His wife of 50 years, Henrietta, passed away last year and you’d think if there was ever a time to slow down and watch the waves crash along the beach, this would be it.

Instead he’s in cold, gray, suburban Detroit on Tuesday, the wet of melted snow on his shoes as he shuffles down a hallway inside the Fox 2 studios here. He’s trying to bang out a 9:20 a.m. live spot to hype Saturday’s junior welterweight “Super Fight” between unbeaten champions Devon Alexander (21-0) and Timothy Bradley (26-0).

To hardcore fans, the bout needs no extra attention; these are two of the best young fighters in the world, the next generation of superstars. To everyone else, it’s a hard sell. That’s the state of boxing and some would assign blame for that on Don King himself.

The fight will take place in the recently vacant Pontiac Silverdome, an 80,000-seat monstrosity near here that will be portioned off to 15,000 seats, a number most believe is probably three times more than needed.

The Rumble in the Jungle it isn’t.

King is undeterred. He believes he can sell this fight, because he’s always been able to sell people things. There are bootstrap tales and then there is Don King, up from poverty and through a life of crime onto the other side of untold glory and riches and indictments. He’s killed and had people attempt to kill him. He parlayed street smarts, a canny guile and a jailhouse education to dine with kings.

One of his three cell phone rings. “It’s Obama,” he deadpans before later adding with humor in his eyes. “Let me tell you this, he’s the best black president we’ve had in history. HISTORY! It’s undeniable.”

Yes, he’s frustrated that two boxers of the caliber of Alexander and Bradley aren’t getting the attention they once would have. This should be a huge fight. But that won’t stop him from trying to work up excitement one interview, one hand shake, one outrageous quote at a time.

In truth, he needs this. Not the money, everything else. Needs the work. Needs the connection. Needs the rush of the sale, the rush of the streets. He can’t stand sitting still. He can’t imagine retirement.

So he treats this humble, mid-morning local TV hit as seriously as he once did a Tonight Show appearance for a Mike Tyson pay-per-view. He’ll then jump in a car and head over to 97.1 The Ticket, the major sports station in town. Then back in the car for more media after that.

This is old-school, blue-collar, pound-the-pavement promoting. It isn’t glamorous. It is exhausting. King just keeps churning.

“I’m a promoter of the people, by the people, for the people,” King says. “This fight is a good one. I don’t have any hesitations or reservations.”

He employs the same crude marketing skills that drove his numbers operation back in the 1950s -- he makes himself impossible to ignore. And once people see him, they fly around cubicles and across restaurants. They snap their heads toward a working television and listen. He’s famous. He’s infamous. It’s all the same.

Assigned to handle the Fox 2 interview is anchor Lee Thomas, who says the key with a guy like King is letting him go on a colorful rant without letting him overtake the entire live segment. King is the master of malapropisms, butchered analogies, tangential Bible stories and other assorted comical incidents. No one can keep up. It’s part of the shtick.

“I’m here with the great Don King,” Lee Thomas says.

“I’m here with the great Lee Johnson,” King says.

“Lee Thomas, too,” Lee Thomas says with a laugh.

King doesn’t hear him; soon he’s off comparing his hair to the story of Samson and Delilah. Or something like that. Perhaps not even King knows.

He does manage to slip in a “January 29th at the Silverdome” line every third sentence or so.

Don King was going to be a lawyer, no small dream for a black kid from Cleveland’s John Adams High School in 1949. He was set to attend Kent State as one of its few African American students.

“Everybody was proud of me, you know, black boy going to college.”

To pay for it, King spent the summer working with his brother as a numbers runner. There were no state lotteries then so people would bet with local bookies. The “drawing” was determined by the last digit of the closing of three New York stock exchange charts printed in the newspaper.

“If the 'advances' is 323, the 'declines' is 230 and the 'unchanged' is 222, then the number is 302,” King said. “You couldn’t rig it.

“It was the ‘numbers game’ when black people had it,” he continued. “When white people took it over, they called it the lottery. Then they’d say they were going to use the lottery to help education. And none of that ever happened. But I learned on that, I learned you need to put the right touch on things to sell them.”

Even as an 18-year-old, would-be college student, King was a prodigious earner, talking everyone in his territory to bet more and more. He was relentless. Then one day he lost a woman’s betting slip -- it wound up stuck to the bottom of a flower pot. Her number came in. His boss said since it was King’s mistake, he was on the hook for the payout. There went the tuition. There went college. King became a full-time numbers man.

Within a year, he was in charge. He was a natural, folks flocking to him. Just like now, it’s all about connecting with people, creating the perception of entertainment, making them think he’s in on something they aren’t. When someone’s number hit, King would stuff the cash into a bag and take it to a bar where he’d pay out in front of everyone.

“Generate more excitement,” King said. “They’d all be saying, ‘He ain’t gonna pay, the son of a bitch won’t pay.’ They’d all start getting trepidation. Then I’d run into the bar and celebrate with them. Buy everyone a drink. They’re celebrating and I’m wounded. That’s my money. I’d be sweating (but) I’m paying out with a smile.”

It was a brutal racket, of course, something that suited King just fine. Standing just over 6 feet tall, King was often seen with a huge cigar in his mouth and a .38 tucked under his belt. On the street he was known as Donald “The Kid” King.

His reputation as a man not to be messed with was enhanced in 1954 when he shot and killed a guy named Hillary Brown. Since Brown, at the time, was trying to rob one of King’s gambling operations (an illegal gambling operation, but still), it was ruled “justifiable homicide.” King went free.

At its apex, King’s operation was said to be grossing $15,000 a day. That attracted the attention of, among others, a man named Alex “Shondor” Birns, a notorious local mobster whose career stretched from Prohibition to his death in 1975, when his Cadillac was bombed so violently that his body was blasted through the roof and wound up in pieces all over a church fence. Birns was 68 years old when someone needed him to be

that dead.

“Alexander Birns,” King recalled wistfully. “He couldn’t be made because he was Jewish, but he was the toughest son of a bitch I ever met.”

The mob demanded protection and insurance money, and King was willing to go along with the deal if they would offer short-term loans in case of a major loss. King said they agreed. Then when he needed a loan one day, he was refused.

“They said, ‘No, we ain’t going to loan you anything.’ I said, ‘I’ve been paying in all this time, what’s the redeeming value?’ ‘Ha, ha, ha,’ they laughed. I was willing to go along with any program but once the program was violated I said, ‘(Expletive), I ain’t paying this no more.’

“Then my house got blown up and I got shot in the head.”

King survived both the bombing and later the ambush in his driveway, although he still sports several bullet pellets in the back of his skull.

“Put your finger right there,” he said. “You feel those pellets?

“Let me tell you, you’re talking about a guy who only through divine providence is sitting here talking to you. I thought the mob would kill me. I was defiant, defiant, defiant.”

King held off the wise guys and his power grew. He was both beloved and feared. Then came 1966 when an employee, Sam Garrett, “ran off with (some) money,” according to King.

King hunted Garrett down at a local bar, dragged him outside and proceeded to engage in what police charged was a hellacious battle. Garrett wound up dead, his head smashed against the sidewalk.

“We were fighting,” King said Tuesday. “(It was) what I call the frustrations of the ghetto expressing themselves. And when you’re fighting in the ghetto, as you can see nowadays, and it was even worse then, you don’t (back down). So you go out there, you’re kicking and fighting and you have a tragic occurrence.

“His head hit the ground. Those are the things that happen.”

King wound up having his charge reduced to manslaughter (a sweetheart deal) and was shipped to the Marion Correctional Institute for just four years.

For King, it was enough. He was done with running numbers. He said he was profoundly remorseful of the death. He vowed to change. “I didn’t serve time, I made time serve me.” He hooked up with the prison priest and started reading. His first book was “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor and philosopher who believed in duty and service. It’s no light fare. King went from there.

“It was like an addiction,” he said. “I’d scan the bibliographies. I’d chase the footnotes. I’d see a book in the footnotes and then I’d go get that book.”

He got out in 1970 and opened a night club, the Corner Tavern in Cleveland. There he met Muhammad Ali, who was exiled from boxing after refusing to report to the military. The two hit it off and in 1972 King promoted an Ali exhibition fight to benefit a local black hospital. It sold out Cleveland Arena and raised an astounding $80,000.

That was his foray into boxing -- promoting The Greatest.

“I never did believe in working my way up the ladder,” he said.

Behind King’s Florida mansion sits a 12-foot tall replica of the Statue of Liberty. King had it installed because he saw it as an appropriate and beautiful tribute to the America he loves so well. His fellow Florida mansion dwellers saw it as a gaudy eyesore. Soon after it went up, they demanded he take it down, citing some kind of neighborhood ordinance.

King told them he wasn’t going to touch it, but went right back to his old gangland days and made them a sales offer they most certainly could refuse. Nothing’s changed with Don King. If it was so unpleasant, he said, they could bring their bulldozers in to knock the iconic symbol over. There was just one catch.

“I’ll get ABC, NBC, CBS in here (to film it),” King told them. “Go ahead, tear it down.”

The statue has not been torn down.

“Lady Liberty, man,” and with that, the old con man/promoter laughs again and heads

back to work.