The NFL's current labor situation must have Vince Lombardi and Tom Landry laughing upstairs.

They never really knew such weighty issues in their historic roles – not as head coaches of the Green Bay Packers and Dallas Cowboys; certainly not as New York Giants assistants under Jim Lee Howell in the mid-to-late 1950s.

Throughout Lombardi's legendary pro coaching career, from when he became Howell's offensive boss in 1954 to his death from colon cancer in 1970, just before his second year as Washington's head coach, he never encountered a work stoppage, much less the ebb and flow of personnel in the free agent era.

Landry -- the Giants defensive back who became his unit's mastermind the same year Lombardi arrived until 1959, when he left for expansionist Dallas a year after Lombardi departed for Green Bay -- endured one work stoppage in 1987. But his firing after the 1988 season, 29 years and 270 wins as the Cowboys' lone head coach, saved him from answering questions about other tangled issues like free agency and salary cap.

It was a different time back then, especially as the two honed their professional coaching styles with the Giants. Really, the only roster issues an assistant had to worry about in the '50 were injuries and retirement. Unless traded or released, players were tied to their teams forever.

There wasn't even a players association to represent them until 1956, and at that point it had little pull. The few players who joined up in the early days risked being cut. Even Hall-of-Fame quarterback Norm Van Brocklin, a big proponent of players rights back then, absented himself from the first official meeting for fear of showing up in a newspaper photo.

Owners, coaches, even assistants, dictated when, where and how a player would work in the NFL. Contract negotiations were simple. An owner like Wellington Mara put a piece of paper with a bunch of legalese and a number in front of the player, and he signed it. If he balked, there might be some yelling. There might be some threats. But there were no lawyers or agents, and the player eventually accepted that low, low figure if he at all intended on pursuing his pro career.

Sam Huff, who helped the Giants' defensive assistant revolutionize football at the new middle linebacker spot in Landry's brainchild, the 4-3 defense, remembered in his book "Tough Stuff" of one of the first "negotiations" he had with Mara. A married rookie with a child in 1956, Huff wanted an extra $500 (on a $7,000 salary) to pay off some furniture he'd just bought. Mara's quick agreement led Huff to believe he'd received a bonus.

When the linebacker found his first game check to be light by $500, he asked Mara, "Why was I shorted $500?" Mara explained the money was merely an advance on the contract. "You gotta learn, Sammy, in this business there’s a big difference between an advance and a bonus," Mara said.

As one can see, the business end back then was all one-sided toward the owners. There were only a few factors that could pull a team apart, with the only unavoidable one being severe injury. But the general comings and goings of players were left completely up to management.

If a team had good players who bought into the system, as the Giants had, they could be kept for as long as a coach and owner wanted.

That was a huge factor in Lombardi's and Landry's success under Howell (at right). Not only did "Slim Jim" hand his dual geniuses the keys to the car, he let them drive it anywhere they wanted. Aside from some mild input from above, Lombardi and Landry called the Giants' shots that won a championship in 1956 and put them in the '58 and '59 title games. They never suffered a losing season, the only team in the league to achieve that from 1954-59.

They called those shots with basically the same players. Old standbys Charlie Conerly, the quarterback who came to the Giants in 1948, Frank Gifford, who arrived from USC in '52, and left tackle Rosie Brown, the team's 27th-round draft pick in ’53, headed up Lombardi’s offense until he departed weeks after the Giants' overtime loss to the Colts in the championship contest that history knows as "The Greatest Game Ever Played." Once Landry's defense came together for good in '56 with the drafting of Huff and Jim Katcavage, the acquisitions of Andy Robustelli from the Rams and Dick Modzelewski from the Lions, and the drafting the year before of Rosie Grier, the core wore the NY on their helmets into the 1960s.

The contracts each of those luminaries would have commanded in today's open market -– whatever form that will take in a new collective bargaining agreement -– would have made it impossible for the Giants to keep those groups intact. Without those players, it is arguable that Jim Lee Howell's, and then Allie Sherman's teams would not have triggered a golden era where the Giants won a championship and made it to six title games between 1956 and '63.

Retirement was basically a player's only option. And Gifford almost took it. On the night in early '59 that Lombardi told Gifford over dinner at Al Schacht’s Steakhouse in Manhattan that he was leaving for Green Bay, Gifford had actually thought about leaving himself.

"Told me he was gonna go," Gifford said. "We were both sad. I actually didn’t think he was gonna do it. It wasn’t that big a deal with me at the time. I was thinking myself whether I should play anymore."

The 1958 championship game had left both men at a crossroads. The guilt Gifford felt over his two fumbles and missed first down that ostensibly cost his team the championship in regulation had left him thinking about retirement. Young, handsome, with dough rolling in from endorsements and movie roles, Gifford made far more money off the gridiron than on it.

He knew well that a guy didn’t have to take a physical beating on a Hollywood sound stage. He also knew that Howell was far less appreciative of his competitiveness than Lombardi or his teammates. Barely tolerant of the head coach before, he lost all respect for him in 1957 when, a season after Gifford was named MVP of the league, Howell chewed him out as “one of those Hollywood characters” when a commercial he was shooting made him late for a meeting.

Gifford would think about retiring several more times, but even a devastating concussion at the hands of Philadelphia's Chuck Bednarik in 1960 wouldn’t keep him from resuming his career.

Eventually, that Giants team did break up. Sherman traded off much of Landry's vaunted defense, with its centerpiece, Huff, shuffled off to Washington after the 1963 championship game loss to the Bears. Robustelli retired. Gifford went into broadcasting.

It would take the Giants until 1981 to reach the playoffs again, but not because of player freedom. Bad trades and bad talent caused that.

It was an era where management built or dismembered at will. One only wonders whether Lombardi and Landry could have won under today’s system –- however that's going to look once courtroom football transitions itself onto the gridiron once again.

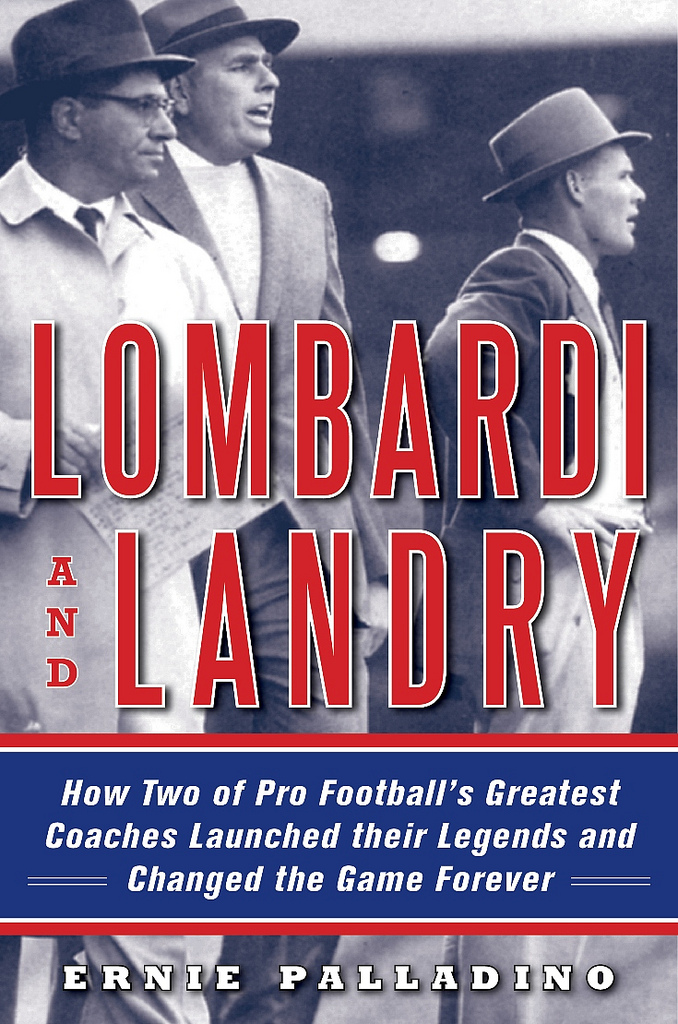

-- Ernie Palladino is the author of "Lombardi And Landry: How Two of Professional Football's Greatest Coaches Launched Their Legends and Changed the Game Forever." It will be published in September and is available for pre-order on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Palladino has covered the New York Giants for more than 20 years, first with the Journal News in Westchester, New York, and now at TheGiantsBeat.com. You can follow him on Twitter @skadoodles.