LAS VEGAS – Bill Walters smiled broadly, as he often does, and reached across the seat to hand me a large package: A bag containing $55,000.

It was a brisk late fall Sunday morning in 2006, and the professional gambler, who was profiled Sunday on "60 Minutes," was trying to prove a point. I was a sports reporter for the Las Vegas Review-Journal newspaper and had long been familiar with Walters, having covered both golf and sports betting for many years.

Many professional sports bettors had begun to call me earlier in the year complaining that the city's sports books were declining to take their bets. Several said no matter what the posted limit was on the sign hanging on the wall of the sports book, the books were refusing to take the action.

They were, the bettors moaned, more than happy to take the sucker bets, the $20, $50 and even $100 parlay cards that tourists loved to play and which overwhelmingly favored the house. But the books weren't, they said, willing to take their action.

I followed up on their tips, but most sports book directors scoffed at the notion. Given that I didn't have $11,000 laying around to go make a bet in search of a story, I didn't have anywhere else to go with it.

Until, that is, I was having lunch with Walters at one of the golf courses he owned in Las Vegas when I was working on a golf story and happened to mention the complaints the bettors were making about the books.

I knew, of course, that Walters was the most prominent sports bettor in the world, but I rarely quoted him in my betting coverage because he preferred to keep that aspect of his life private.

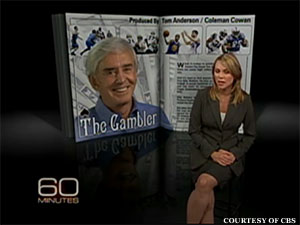

It was laughable when "60 Minutes" correspondent Lara Logan referred to Walters in her piece on Sunday as "almost elusive as Howard Hughes, avoiding publicity," given that he had just about every reporter in Las Vegas on speed dial. If you covered golf, or business, or sports betting in Las Vegas, Walters was hardly elusive.

I mentioned to Walters that many bettors were complaining that they couldn't make so-called limit bets. To my surprise, Walters said they were correct. I was skeptical, but he said he would be willing to run an experiment to prove it.

We agreed to meet in the parking garage on top of the Gold Coast on a Sunday morning. When I pulled into the garage, I saw Walters in his car, awaiting me. I walked over and he suggested I go to the Rio Suites, which was next to the Gold Coast, to try to put in five limit bets. At the time, the signs in the Rio's sports book indicated they would take a maximum bet of $11,000 on an NFL game.

Of course, they'd take more on that, depending upon the client. If it was a high-rolling Asian gambler, they'd pretty much accept as much as he'd want to bet. But if the bettor were just someone walking in off the street, the book rules indicated they'd accept a maximum of $11,000 on an individual bet.

So Walters reaches across his seat and hands me this giant block of cash: $55,000, and tells me to go make five bets at $11,000 each. To him, that's no big deal. He'll bet seven figures a day, as "60 Minutes," reported, and wagered more than $3 million on the Saints to win Super Bowl 44. To me, though, it was a fortune and I wasn't comfortable in the least.

He kept talking, but for probably the next 30 seconds, I didn't hear a word he said. My heart was racing. I was short of breath. Holding onto this amount of money was staggering and I suddenly became fearful.

All I had to do was walk down the steps of the garage, run across the street and into the door leading to the sports book at the Rio. Then, it was a short trip down the hallway to the sports book. I only then had to walk up to the window and place my bets.

I'd been around sports betting most of my life. I grew up in Pittsburgh and learned about parlay cards before I was a teenager. While I was still in college, I once lost my entire paycheck betting on Sugar Ray Leonard to defeat Roberto Duran in their first match, in 1980 in Montreal.

I'm not much of a bettor, because losing feels worse to me than winning feels good, so I had only bet a few times in my two decades living in Las Vegas.

When I did bet, you can't bet it wasn't $1,000, let alone $11,000.

All I could think of when Walters handed me the money was something going wrong: What if someone watched me take it and mugged me on the way down? What if the money dropped out from beneath my coat and I had to chase it around? What if someone in the sports book were to pick my pocket? There was a lot that could go wrong with this, I knew. I wasn't so thrilled I'd agreed to the scheme, but there was little I could do at this point.

I headed down the steps of the parking garage, encountering no one. I jogged across the street and into the Rio. I walked down the hall and entered the sports book. The scene was typical of an NFL Sunday in Las Vegas: There were lots of loud, overweight guys wearing player jerseys that were more than a little too tight, drinking and eating and comparing notes.

I made it a point to try to find the Rio's sign to confirm the limit it would take on one game. It was, as I knew it would be, $11,000.

I sat in one of the chairs and looked at the board with all of the lines. My heart was racing, and at this stage, I'm not sure why. I knew all I had to do was walk up, make the bets, get the tickets and return to Walters to say, "I told you so."

I waited a few minutes to gather my courage and then walked to the window. I told the ticket writer that I wanted to bet $11,000 on the Saints. He said, "OK," typed into his computer and waited a second.

I was expecting to hear the screech of the printer making my ticket, but nothing happened. The ticket writer was reading his screen. He frowned and asked if I were staying at the hotel. I replied that I was not. He asked if I were a member of some sort of player's club they had. I said no. He asked me to wait a moment.

He called a supervisor and they had a brief discussion. The supervisor informed me that they weren't interested in my bet. I asked him why and he just repeated they weren't interested in taking the bet. At that point, I told him I was a reporter and wanted to ask a few questions.

He referred me to the director, who wasn't there, and said he could speak no more. He walked away. (None of the books would discuss why they were declining, saying it was a private decision.)

That meant I had to leave and walk across the street again with the $55,000 on my person in order to return it. Once again, I encountered the same fears I had a few minutes earlier.

As I made it to the top of the garage, I spied Walters.

"Let me guess," he said, beaming again. "They wouldn't take it."

I explained the story to him and handed him the money back.

Never in my life was I so glad to get rid of $55,000.

And never again would I think of making a bet, limit or not.

Unlike Bill Walters, my gambling days were done.