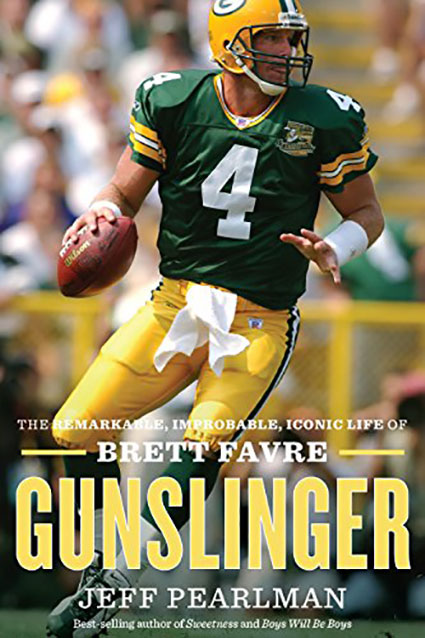

Gunslinger: The Remarkable, Improbable, Iconic Life of Brett Favre draws on more than 500 interviews, including many from the people closest to Favre. Author Jeff Pearlman charts an unparalleled journey from Favre's rough rural childhood and lackluster high school football career to landing the last scholarship at Southern Mississippi to a car accident that nearly took his life.

On the afternoon of July 14, 1990, Brett Favre, his older brother Scott and two Golden Eagle teammates, Toby Watts and Keith Loescher, met on Dauphin Island, Alabama, for a day of fishing off the Gulf of Mexico.

There was nothing particularly unique or special about the plans -- "A boat, lunch meat, beer," said Watts, a defensive end who had transferred to Southern Miss after a year at Southern Methodist. "Just a college day of it, hanging out" -- and after several hours of eating and fishing and drinking and drinking and drinking and drinking, the young men split up. Watts returned to his hotel room, and the three others made the 95-mile trek back to Kiln, where they were to have dinner with Bonita and Irv. Keith and Scott were in one car; Brett drove his white 1989 Maxima.

The straight shot along I-10 West was scenic, but hardly noteworthy. Before long, the cars were rolling through the Diamondhead resort development, a stone's throw from the Favre home. What happened next -- at approximately 7:45 p.m. on Kapalama Drive -- is somewhat confusing. In 1997, Brett told Steve Cameron, author of the book Brett Favre: Huck Finn Grows Up, that he was distracted by the high beams of an oncoming vehicle and he was not speeding. In 2007, he told Mark McHale -- his former coach and the author of 10 to 4 -- that he merely "slid off the road" (high beams never noted). In his 1997 autobiography, he also failed to mention an oncoming car, simply that he was traveling above the speed limit (about 70 mph in a 35 mph zone) and that his right front tire, "hit some loose gravel on the shoulder." Favre wrote that he straightened the wheel, but, "because I was going so fast, the car shot across the road." When asked about the accident by Russ Brown of the Louisville Courier-Journal, he said he might have been blinded by, "the setting sun." In 1991 he told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution that "they'd been repairing the road and I forgot it."

Loescher, trailing Favre by no more than 20 feet, witnessed the entire incident. "Brett was probably going 60, and he just kind of went off the edge of the road," Loescher said. "He overcorrected and his car just shot across the road and started flipping sideways and it rolled up to a stop at a telephone pole. There was actually a point when it was flipping, where if we hadn't hit the brakes we could have driven right underneath his car. It went off the side of the road and into a telephone pole and up on its side."

Loescher slammed the brakes and backed up. He sprinted toward the Nissan, glanced through a window and saw no Brett. "He was gone," Loescher said. "He wasn't anywhere in the front." Loescher shifted his view to the rear of the vehicle, and spotted his friend, crumpled behind the backseat along the shelf. Blood covered his left knee. Shards of splintered glass were everywhere. "I punched the window -- the driver's side window -- three or four times," Loescher said. "I couldn't break it. So I ran to Scott's car and opened the back." An avid golfer, Scott kept his clubs in the trunk. Loescher grabbed a 3-iron and hammered it into Brett's window, causing a slight crack in the glass before the clubhead broke off and flew through the air. "I'm standing there with the shaft of the club, and I started stabbing the window," Loescher said. "Before I got all the glass out Scott jumped into the car."

"I drug him out the back as quick as possible," Scott said, "because I had no idea whether the car would catch on fire." The two men grabbed Brett beneath his shoulders and laid him on the side of the road. They screamed his name, but he did not respond. "I thought he could have been dead," said Loescher. After a couple of seconds, Brett mumbled a handful of nonsensical words. Then -- "Scott, stay right here, don't leave me. Am I gonna be alright, Scott?"

"Hell, yeah, you're gonna be alright," his brother replied. "You'll be fine."

Scott and Keith tried to flag a bypasser down. A woman finally stopped, and immediately lectured Scott on safe driving. "She was bitching about how we ended up there," Loescher said. "We were driving too fast or too recklessly or whatever. I remember Scott started yelling back at her." Brett, still on the ground, tugged at Scott's leg. "Be nice," he said in a whisper. He then complained about severe stomach pain, so Loescher pulled his shirt off. A purplish-red steering wheel imprint was embedded into Brett's torso. At long last, the sound of sirens could be heard.

"I remember Scott screaming at me, 'Are you alright?'" Brett recalled. "I had one of those concussions where you don't know who or where you are, but I was talking."

Bonita Favre was attending a function at St. Paul Catholic Church in Pass Christian. Karen, Irvin's sister, excused herself to take a phone call. She returned moments later, face ashen. "We've gotta go!" she said. "Brett's been in a wreck not far from the house." They rushed to the scene. Lights were flashing; police officers and firemen lingered. "I saw the car," Bonita said, "and thought, 'Oh my, they're dead.'"

Bonita rushed toward Brett, who was on a stretcher. "Mama, I'm alright!" he said. "I'm alright!" He was taken to Gulfport Memorial Hospital. "I screamed with every bump we hit because it hurt so badly," he recalled. "I'd scream every time they moved me."

Shortly after he reached the emergency room, a groggy Favre was told by the attending physician that, with his injuries, football wasn't an option for the upcoming season.

"Just watch me," he replied.

The next morning, readers of the Clarion-Ledger opened up their newspapers to the frightening headline FAVRE HURT IN WRECK. Staff writer Robert Wilson, who learned of the accident two hours after it happened, filed a detailed piece, explaining that Southern Miss's star quarterback suffered a hematoma (a swelling caused by a collection of blood) on his liver. "He has a lot of soreness in his abdominal wall," Dr. Jare Barkley, the treating physician, said. "We hope his body can absorb it. He is in a lot of pain and under medication, but he is alert and in full possession of his faculties. He had a concussion briefly. He was like a prize fighter being knocked out. He doesn't remember the accident."

The article quoted multiple sources, filled in myriad gaps (he had six stitches in his left kneecap, a severely bruised left arm, a bruised vertebra and a right side that was black and blue from ribs to hip) and left Southern Miss fans to wonder whether Brett Favre would recover in time for the upcoming season. Two days later, a piece from Billy Watkins in the Clarion-Ledger added a bit more information, including that the cause of the wreck, "is under investigation."

One detail remained secret for the next two and a half decades. After the accident, Slim Smith, sports editor of the Sun Herald, called the hospital to find out whether Favre's blood alcohol content had been above the legal limit of .08 percent. Smith found a hospital employee who was willing to share the information but then, according to Smith, backed out with cold feet. It was made clear he was not allowed to speak with the press. The reason: Brett measured above the legal limit, but benefited from a system that had long protected local athletic heroes. "Brett almost certainly got preferential treatment from law enforcement," said Smith. "It's not a big surprise."

"We were all shitfaced," said Loescher, never asked about the specifics of that night until years later. "I can just hold up a little better."

Brett Favre should have been arrested on DUI charges. In a region that loved and protected its football stars, however, he never was.

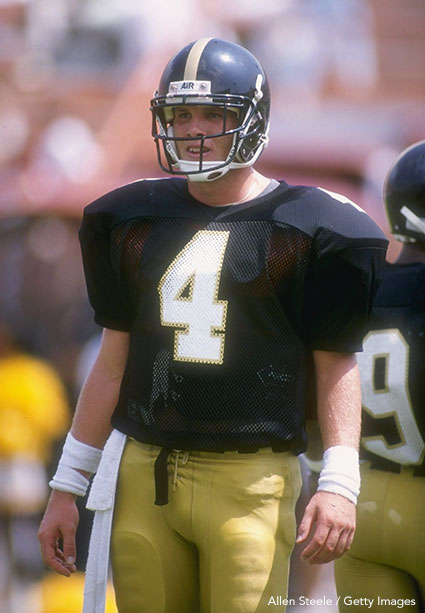

On the morning of September 8, less than two months after he nearly perished, Brett Favre and the other members of the Southern Miss football team walked out onto the Astroturf surface of Birmingham's Legion Field, knowing little about their pending fates. On the other side of the 50-yard line, the Alabama Crimson Tide players stretched, jogged, played catch. Although it was the season opener, as well as the debut of Tide head coach Gene Stallings, the team appeared calm. This wasn't a matchup against Auburn, after all, or even Florida, Georgia, or Louisiana State. It was Southern Miss, and a game they scheduled for the win.

Favre was emaciated and physically untested. He had missed his team's season opener a week earlier (an unimpressive 12-0 victory over Division II Delta State), and was still feeling the effects of the wreck, as well as an ensuing blood blockage that resulted in the extraction of 30 inches of his intestine. Now, a physical shell of his old self, how would he hold up against John Sullins and Eric Curry, two of America's elite pass rushers? Nobody was quite sure. "That was my first college game, and I was pretty terrified," said Darian Smith, a Golden Eagles offensive tackle. "You grow up watching Alabama, loving or hating Alabama. And now you're playing Alabama, at Alabama."

When the team returned to the locker room for final preparations, Curley Hallman, the Golden Eagles head coach, gathered everyone around for last thoughts. The players sat on wood stools. It was brutally hot (95 degrees), without air-conditioning or fan. "OK," Hallman said, "I want all of the offensive linemen to stand up. First team, second team, third team -- actually, all of y'all. Stand."

The 76 young men rose. Still, silence. "Boys, it's on you," Hallman said. "Brett's about 70 percent and he's going. And he better not get touched."

A pause.

"A lot of you boys are from the University of Alabama, a lot of you boys dreamed of playing for Alabama. But they didn't want you. You were too small or too slow or whatever. Well, we wanted you. We want you. Today is your chance to show them what they're missing ... to show them what kind of stupid mistake they made ..."

With that, the Southern Miss players charged out the tunnel and onto the field. Favre walked to the sideline, gripped a ball, and began to warm up. "To watch him throw -- wow," said Gary Hollingsworth, Alabama's quarterback. "When a guy throws from college hash marks to the other side of the field, and the ball never gets lower than head high off the ground ... as quarterback you sit and watch that and just go, 'Damn. I can't do that.' And he wasn't even healthy." By now, Stallings, who later described Favre as looking "like a damned scarecrow, his uniform hanging all loose around him and stuff," was fully aware of whom his team would be facing. Before kickoff, he spoke to his defensive starters. "Go hard," he said, "but don't hit Favre after he releases the ball." The words shocked Alabama's pass rushers, but not Hallman, who played under Stallings at Texas A&M and later coached with him. "Gene is a quality man," Hallman said. "He did things the right way."

Alabama received the opening kickoff, marched down the field, and easily reached the end zone on an 18-yard Derrick Lassic touchdown run with 12:07 remaining in the first quarter.

It was Southern Miss's turn. Favre took a deep breath and prepared for the most meaningful jog of his young football life. Several months earlier, before the wreck, Favre had volunteered to work at a summer high school football camp held on the Louisiana State campus in Baton Rouge. The counselors -- hired by a Golden Eagle assistant coach named Daryl Daye -- were all regional college players, including a large number of LSU standouts. Favre gravitated toward Shawn Burks, a linebacker who enjoyed a cup of coffee with the Washington Redskins. Whenever Burks completed a drill, or coached a successful play, he would scream out, "Whiskey!" Nobody knew why, but the exclamation alone -- expressed with such gusto -- reduced Favre to hysteria.

Now, as he jogged out onto the field, trailing 7–0, the pressure of a football program heaped upon his shoulder pads, Favre looked at Daye, grinned slyly, and screamed, "Whiskey!"

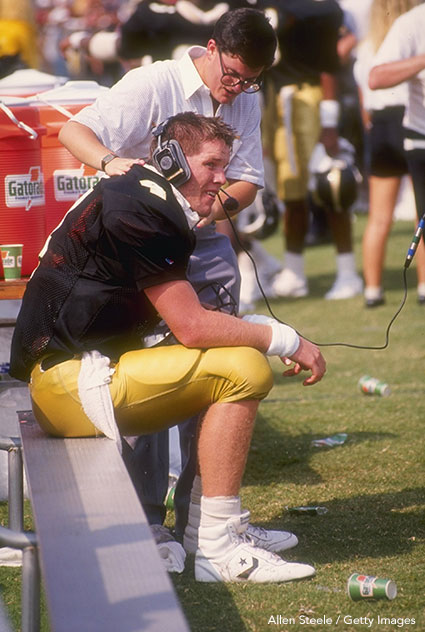

Favre entered the huddle and was choked up by the tears streaming down his teammates' cheeks. "It was a great reception," he recalled. "Right up to the snap." On the first play, Favre dropped back and was drilled into the ground. When he failed to rise, Doc Harrington, the trainer, sprinted toward his side. "Oh, God, Brett, what's wrong?" he asked.

Favre struggled for breath. "Doc," he gasped, "I got hit in the balls."

"Oh, good," Harrington said. "Stay down."

"No," he replied, "not good."

Favre played terribly throughout the first two quarters. Alabama held a 17–10 halftime lead, and outgained Southern Miss by 241 yards to 36 yards. The Southern Miss quarterback returned to the locker room exhausted and beaten up. Save for the 3 series where Whitcomb provided a breather, Favre took all the snaps. His numbers were awful, his impact immeasurable. "You could see the emotion he brought to those players," said Hollingsworth. "Shit, he'd roll out, duck, move, spin, run, drop back and throw it, and somehow the receiver would be there. That team believed in Brett, and believed they could always win as long as he was playing."

During his halftime speech, Hallman pleaded with his players to keep the score close. "If we can stay within a touchdown, we'll win this," he said. "The pressure is entirely on them. The closer we are, the more nervous they'll feel."

Thanks to a series of brilliant runs from halfback Tony Smith, Southern Miss entered the fourth quarter tied with Alabama at 24. This was supposed to be Stallings's coronation as the heir apparent to Bear Bryant. Instead, the Alabama offensive line looked inept, and its defense couldn't make big stops. Alabama had four turnovers and 54 yards in penalties. "At times," wrote Chuck Abadie in the Hattiesburg American, "[the Tide] had trouble even getting the proper 11 players on the field." With 7:23 left in the game and the score still deadlocked, Southern Miss took over at its own 20. There would be no more Whitcomb insertions, and no more questioning Favre's readiness. This was his game.

Slowly, meticulously, the Golden Eagles drove down the field behind a series of runs and short passes. Favre's moment came five plays into the series, when he danced around the pocket, avoided a charging Sullins, ducked, pumped, and threw a laser to halfback Eddie Ray Jackson over the middle for 34 yards. Shortly thereafter Jim Taylor -- "a straight-on kicker with one of those clown shoes," said Daryl Daye -- booted a career-long 52-yard field goal, and Southern Miss somehow escaped with a 27–24 victory. "This isn't supposed to be happening!" Allison screamed to McHale in the coaches' box. "This is Alabama, Hoss! Alabama!"

At midfield, Hallman and Stallings embraced. "Curley," Stallings said, "I just hope your quarterback is OK."

Hallman laughed.

"Coach," he replied, "my quarterback is fine."

-- Excerpted by permission from Gunslinger: The Remarkable, Improbable, Iconic Life of Brett Favre by Jeff Pearlman. Copyright (c) 2016. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound and iTunes. Follow Jeff Pearlman on Twitter @jeffpearlman.