This Sunday, the sounds of grunts will fill the air at the U.S. Naval Academy's MacDonough Hall in Annapolis as Army and Navy faceoff for the Commander's Cup in powerlifting. Every year for the past ten, Army has schooled Navy in the competition -- but it wasn't always that way.

Before Rick Scarpulla showed up and turned the Army team around, West Point wasn't known for churning out champion powerlifters. Scarpulla's own team demolished West Point at a meet in 2002, and one of the Army freshman approached him after the competition, hoping he could teach the cadets a few things.

"Not long after, I came home and my wife said, 'Honey, West Point called,'" Scarpulla says. "I had no idea why they'd be calling, but turns out they wanted me to be their permanent coach."

Scarpulla turned their program around, becoming not just the designer of the U.S. Military Academy's powerlifting strength program, but a true friend to many of the young cadets. Years after graduating, they'll call him every once in a while to catch up. Sometimes they are calls for support coming from Afghanistan or Iraq; other times they are calls of celebration to tell of marriages and babies (one named Richard).

Scarpulla's clients run the gamut, from world champion powerlifters to college athletes like Wichita State's Cleanthony Early, two -time NCAA-JC Basketball Player of the Year to NFL player Adam Bergen and Lonnie Matts.

But like his West Point team, the 50 year-old coach didn't always seem destined for powerlifting greatness.

He was a junior in high school in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., when a woman in a sizeable El Dorado ran a red light, T-boned Scarpulla's car and spun him across three lanes into a concrete barrier.

"My car bounced off that wall and got hit by a bus," he recalls. "I 'died' three times, my left leg was broken in nine places, my shoulder was smashed and my face was shattered."

As far as his leg, Scarpulla's choices were amputation, a long-term body cast or new surgery involving a metal plate for his hip. Remembering the discomfort and, well, the stench of having a cast on his arm for a few weeks as a kid in hot, sticky Florida, Scarpulla opted for the surgery. For two years, the former high school athlete couldn't walk. He went from his bed to a wheelchair to crutches and then a cane, hating himself as he continued to lose more and more muscle. By the time he could walk, the 6-foot Scarpulla weighed just 107 pounds.

"As soon as I could walk, I started going to the gym at quarter to 11 at night. I called it 'training in shame.' If someone came in, I would just put the weights down and pretend I was wrapping it up," he says.

One day in 1983, Scarpulla was lifting incognito and watching a group of huge guys working out in the corner.

"I'm watching these big guys, making noise and just slapping the plates onto the barbells," he remembers.

Eventually, the alpha male of the crew approached him.

"I want you to lift with us," the guy said. His name was Frank Dias.

Scarpulla was petrified. He declined, but the guy persisted, eventually offering to just lift with him.

"I still get choked up when I think about it," Scarpulla says.

Dias is now a world champion powerlifter, and one of Scarpulla's closest friends. He joined Dias' group and even competed with them, coming in at dead last in his first meet, squatting 350 and benching 250.

"I remember running off the platform to the stairwell and just exploding into tears."

Now, he squats 800.

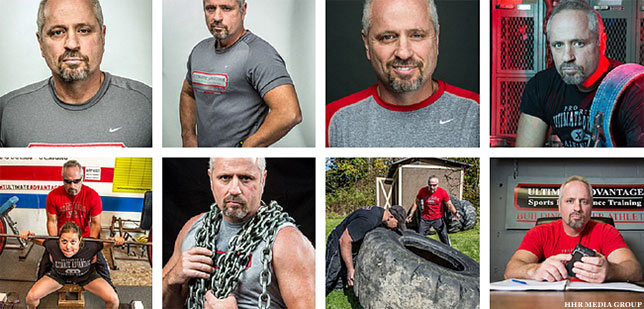

Lifting became his life's passion, and though he worked construction during the day, Scarpulla began learning from more of the best, including Bev Francis, one of first female celebrity bodybuilders. He also worked with Nike, eventually building up a long list of clients. He started his own program, the Ultimate Advantage Training Program, and a gym called the Ultimate Advantage Gym just outside New York City. Still, it's clear from the devotion of his clients that Scarpulla has never forgotten what it's like to be an underdog.

"Rick has this old-school coach mentality," says Dylan Hannah, the West Point powerlifting team captain. "If he gives you a compliment, it's like winning the Nobel Peace Prize. It's not that he looks down on us, but he wants to push you to your highest potential. "If he watches you lift and he doesn't say something, you're doing something right."

Hannah says the way Scarpulla incorporates psychology into his training is something he had never experienced as a high school athlete, and the thing that sets him apart from average trainers. If you think weightlifting is all about being a meathead, Scarpulla will make you think twice.

"It took me a while to understand how the mental aspect plays into my lifting performance, and then one day it just clicked," he says. "Rick taught me how to attack whatever you're working out in your head with the weights."

Scarpulla works with college and professional football players, tennis players, Olympic track athletes, soccer players and even swimmers. But he is just as inspired by the regular people who come to him to just get in shape. He works closely with Kevin Kroger, a 45 year-old businessman in New York who is just trying to ward-off the effects of reaching middle age.

"The first day I went there, I saw that white light people talk about," Kroger remembers. "We were doing these different cardio and bag exercises -- he was seeing where I was at. He looked at me and said, ‘I don't know if this is for you.' He knew that would piss me off. That was the motivation I needed."

Kroger says if he could have trained with Scarpulla in high school when he was playing football, he's certain he would have kept playing football in college instead of drinking and partying. He thinks Scarpulla could have helped him get to the NFL.

"My whole premise is based on being a better athlete, no matter what. I want you to be faster, stronger, and more agile with better reaction, better balance and better ocular recognition," Scarpulla says.

His wife teases him about how rich they'd be if Scarpulla charged all his clients full price for his training, but he just can't turn down anyone who wants to learn. He volunteers as a Special Olympics coach, and is beginning to teach Crossfit worldwide. On Sunday, Scarpulla plans to help Dylan Hannah bring home a fourth Army trophy for his bedroom. Beyond that?

"I just want to give my clients and athletes more than barbells and dumbbells."