From Hall of Famers to rookie busts, the Yankees are baseball's most beloved franchise. Jim Kaat, who has the unique experience of playing for the Yankees as well as calling games for them in the booth, had a prime seat to watch it all unfold. In If These Walls Could Talk: New York Yankees, Kaat and Greg Jennnings provide a closer look at the great moments and the lowlights that have made the Yankees one of baseball's keystone teams. Through the words of the players, via multiple interviews conducted with current and past Yankees, readers will meet the players, coaches, and management and share in their moments of greatness and defeat. This excerpt reveals some broadcasting exploits of the iconic Phil Rizzuto.

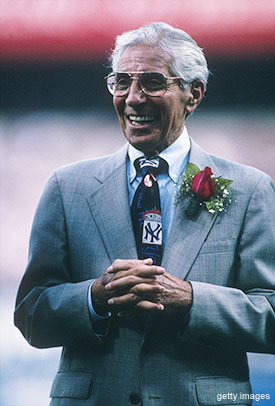

Just like the teams on the field, the production team will have its hits, runs, and errors during the course of the season. Most of the audience never even realizes that. But sometimes funny things happen that are too big to ignore. And the longer you work in the booth, the more the stories accumulate. Phil Rizzuto called Yankees games for more than 40 years, a fact that would probably elicit his famous "Holy cow." Because of his longevity, there are plenty of stories of funny things happening when "Scooter" was in the booth. Rizzuto was a heck of a ballplayer. A slick fielding shortstop and one of the all-time great bunters, he played his entire career from 1941–56 for the Yankees. And that was a good time to be a Yankee. He won seven World Series, including five straight from '49-'53. He's also another one of the Yankees from those dynasty years who earned AL MVP honors. Scooter got his in 1950. Legendary manager Casey Stengel had a chance to take Scooter after a tryout for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the '30s but didn't. After then managing him on the Yankees for years, Casey said of Rizzuto, "He is the greatest shortstop I have ever seen in my entire baseball career, and I have watched some beauties."

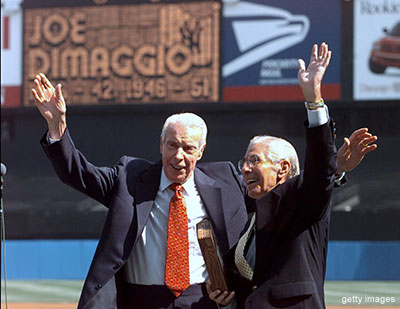

Joe DiMaggio always said, "People loved watching me play baseball. Scooter, they just loved." The year after he retired, he was calling Yankees games along with Mel Allen and Red Barber. He would call games on TV and radio all the way until 1996, two years after his induction into Cooperstown.

I got to work with Scooter and Bill White when I was hired by WPIX in 1986. The basic setup was a two-man booth; one would do play-by-play and describe the action, and the other would be the color analyst who would add insights in and around the action. And then the three of us would rotate. So if Bill and I did the first three innings, Bill and Scooter would do the next three, and Scooter and I would do the final three innings. And our rotation would change every game, but that was how we worked it.

Early that season the Yankees were playing the Indians, so we were in old Municipal Stadium in Cleveland. And the weather was bitter cold. The stadium held up to 70,000 for baseball; I think there were maybe 10,000 there. It felt empty. Scooter and I had the last three innings, and we were freezing in our booth. For me it was no big deal. This was a big job I landed, working for the Yankees, and I was still pretty excited to be there. Rizzuto had been doing this for decades at this point, so the excitement that was keeping me warm had worn off on him probably during the Nixon Administration. After the first half of the seventh inning, Scooter, who always referred to everyone by their last name, said to me, "Hey, Kaat, I’m going to the men's room. Cover for me." And off he went. Now I was a little concerned for two reasons. The first was I had never done play-by-play before. I had always done color. So I wasn't sure if I was the best guy to "cover" for Scooter. The other worry was I had heard stories of Scooter leaving games early. We were about to come back from commercial, and our producer Don Carney asked me over the headset, "Where’s Rizzuto?" I said, "He went to the bathroom." I heard Don sigh and I knew in that moment that Rizzuto wasn't in the bathroom. He had gone outside, grabbed a cab, and went back to the hotel because it was too darn cold. I ended up doing the last three innings of the game by myself.

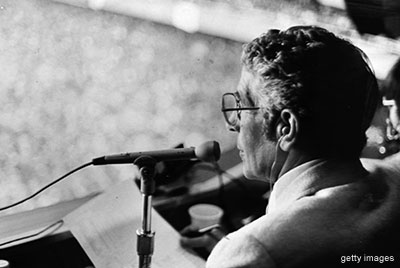

If you watch a broadcast carefully, you will notice that all announcers either have a headset on or an earpiece in their ear. This allows the director and producer and anyone else down in the TV truck to be able to talk to the announcers. Here in the U.S., sports announcers are often referred to by people in TV production as "the talent." I always thought that term was an odd choice. Yes, announcers need a certain amount of talent to do their job, but so does the director, the producer, or the stats guy or gal. They all have talent, so why aren't they called by that name? In the United Kingdom and Australia, they would call what I do being a "presenter." That seems to be a much more accurate and a less potentially offensive term, but it never caught on here. Thus, we will stick with this awkward American convention.

So the "talent" have their earpieces, which are called IFBs. It stands for "Interruptible Fold Back." One of the things you have to master if you are going to be on TV is being able to talk to the audience while someone else is talking in your ear through the IFB. I can tell you from experience, folks, it is not easy. When you hear Al Michaels, Brent Musburger, Joe Buck, or any of those big time play-by-play guys on the air, half of the time a producer is in their ear telling them what's coming up next. For any of you out there who want to be play-by-play announcers, practice talking to one buddy in front of you while another is talking to you on the phone in your ear. Master that and you are halfway home because it gets even more complicated. The producer can talk to all the talent at once or just one at a time. So even if you hear something in your ear, your partner may not.

If the talent has to talk to the producer for some reason while they are on the air, there is a "talk back" button. If you press this, it kills your individual microphone to the broadcast, but the producer can still hear you. Let's say Scooter was calling the action, and I wanted the producer to get a shot of the bullpen. While Scooter's said to you at home, "And here's the pitch ... strike one," I’m on the talk back to the producer saying, "Mariano’s warming up early -- get a shot of it." The director finds a good shot on his wall of monitors, calls out "take Camera Two," and the TD switches it as I'm saying, "Scooter, I think Joe Torre's thinking about a change because Rivera's warming up out in the bullpen." But you have to press that button, or else Ma and Pa in Poughkeepsie are going to hear what you are saying to the truck. And there are things said that you definitely don't want Ma and Pa to hear.

For as long as Rizzuto was on television, he never really mastered the IFB and the talk back. But his charming manner usually got him out of a jam. A few years after I left WPIX, Tom Seaver joined Scooter and Bill in the three-man rotation in the booth. By this point Phil would usually get the first six innings and be allowed to leave by the seventh. In fact, they would often show a shot of the traffic on the George Washington Bridge from the top of Yankee Stadium in the later innings and say, "There goes Scooter now." But one time Scooter had the last six innings. And he was just finishing up the middle innings with Seaver, and Bill White was going to join him for the last three innings.

Bill was an old pro and, unlike me back in Cleveland, he could handle doing both play-by-play and color by himself. The Yankees were down 10–1, and Scooter was not looking forward to doing those last three innings in a blowout. So before Bill went up to the booth, he told the director John Moore that he'd do the last three innings solo so Scooter could leave early. Scooter was on the air with Seaver at the moment, and Seaver was telling a story when Moore told Scooter in his IFB, "Hey Scooter, you can take off at the end of the inning."

Moore, being the good director, only said that into Rizzuto’s earpiece -- not Seaver's. Well Scooter was so excited to hear that he was going home early that he could've kissed Moore. So he does the next best thing and said, "Oh, I love you" over the air. Unfortunately, Scooter didn't hit the talk back. So for the viewer at home, they heard Seaver telling a story about the next batter, when all of sudden, Scooter blurted out, "Oh, I love you!" But Ma and Pa in Poughkeepsie weren’t the only ones who were confused. Remember, Seaver didn’t hear what John Moore said either. He had no idea why Scooter was shouting these affections on the air.

But Tom is a professional and responded, "Oh, Scooter ... I'm fond of you, too." Rizzuto tried to explain himself to Seaver by saying, "I was talking to Moore." To which Seaver replied, "I'm sure he loves you, too." Something like that has happened to every announcer who has ever stepped in the booth.

Mastering the talk back is crucial to being an on-air personality. Another use for the talk back is to correct mistakes while you are on the air. If I hear my partner give an incorrect fact on the air, I quickly hit the talk back and tell the truck, “It was Smith, not Jones,” and they immediately tell my partner in their ear to give him or her a chance to correct it. I, of course, expect the same courtesy. It is never good form to correct your partner on the air.

How many times have you heard an announcer cough or sneeze on the air? Not too often, if at all. That’s because next to the talk back button there is a "cough" button. This kills your microphone to everyone -- even the truck (they don't need to hear you sneeze either) so you can do what you have to do without blowing out anybody's ear or letting the home audience know your hay fever is coming on. The other time you use the cough button is if you get a case of the giggles. Let's face it. Sometimes something strikes you as funny, and you start laughing uncontrollably. It used to happen to me once in a while in church as a kid. Well, if it happens when you are on the air, you just hit the cough button until it passes and then get back to work.

-- Excerpted by permission from If These Walls Could Talk: New York Yankees by Jim Kaat with Greg Jennings. Copyright (c) 2015. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.