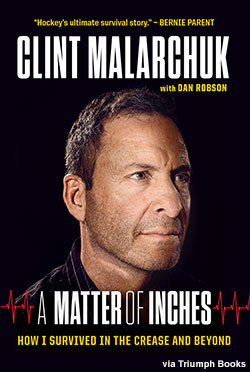

Clint Malarchuk was a goaltender for the Nordiques, Capitals and Sabres while suffering high anxiety, depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. He was also nearly killed when sliced open by a skate across his neck in the most gruesome injury hockey has ever seen. His autobiography, A Matter of Inches: How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond, takes readers deep into his troubled mind. After recovering from the near-death experience, Malarchuk battled depression and alcohol dependence, which nearly cost him his life and left a bullet in his head.

Clint Malarchuk was a goaltender for the Nordiques, Capitals and Sabres while suffering high anxiety, depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. He was also nearly killed when sliced open by a skate across his neck in the most gruesome injury hockey has ever seen. His autobiography, A Matter of Inches: How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond, takes readers deep into his troubled mind. After recovering from the near-death experience, Malarchuk battled depression and alcohol dependence, which nearly cost him his life and left a bullet in his head.

The first time I should have died was a Wednesday. March 22, 1989.

As I prepared for our game against the St. Louis Blues that night, I sat by myself in the locker room at the Memorial Auditorium, staring down at the floor, visualizing myself in net. It was a routine I did before every game. The meditation forced me to focus on one thing: the puck. It quelled the chaos and turned it into a positive obsession. I'd run through stop after stop in my mind -- a pad save, a glove save, a breakaway.

After being lost in an imaginary future, I got off the bench and went out into the hallway, beneath the seats slowly filling with fans. I turned to face a cement-block wall a few feet away, squared my shoulders and crouched. Thud. I threw a rubber ball against the wall with my right hand and caught it with my left. Thud ... thud. Then I threw it with my left and caught it with my right. Thud ... thud ... thud. Each time, the ball bounced off the wall faster than it originally hit it. I threw the ball harder and harder against the wall -- catch and throw, catch and throw.

It was a routine I had picked up from Vladislav Tretiak when I went to his camp in Montreal. It was essential to getting into the right frame of mind to play. Sometimes, I would throw two balls against the wall, tossing one and catching the other at the same time. I forced myself to learn how to do that. On off-days, I'd pick a number and I wouldn't stop the drill until I hit that number without dropping a ball.

Whenever I did these pre-game drills, people would stop to watch me, but I blocked them out of my head. I'm sure the speed was remarkable to them. But in my mind, it was just one fluid blur. Thud ... thud ... thud ... The anxiety became manageable. The repetition slowed everything down and let me focus on one simple thing.

Whenever I did these pre-game drills, people would stop to watch me, but I blocked them out of my head. I'm sure the speed was remarkable to them. But in my mind, it was just one fluid blur. Thud ... thud ... thud ... The anxiety became manageable. The repetition slowed everything down and let me focus on one simple thing.

After the drill, I was still tense, but it wasn’t debilitating. I finished getting dressed with the team and went out for warmups under the lights of the Aud. The tension stayed with me through the shooting drills, but it was all directed towards the game now. Each shot was part of a countdown. My heart pounded throughout the national anthem. My mind and body were consumed by the beat. Thud ... thud ... thud ... thud ... thud ... thud ... And then the players lined up, the puck was dropped, and it all came to a crescendo. Then silence: 20:00 ... 19:59 ... 19:58 ...

The clock crept past the five-minute mark. It was still the first period and I hadn't faced many shots yet. We were up 1–0. The puck was on the boards in the corner and I was on my post. The Blues' Steve Tuttle, a twenty-three-year-old rookie, charged to the net, looking for a pass. One of our defensemen, Uwe Krupp, was right behind him. 4:45 ... The pass came just above the crease -- a backdoor play. I slid across the net. 4:44 ... Krupp pulled Tuttle down from behind and slid into me, skates first. 4:43.

It felt like a kick to the mask. There was no pain, but I pulled my helmet off. And then I saw the blood. It spattered red in the faceoff circle. A stream gushed out with every beat of my heart. It's an artery. I grabbed my neck, trying to keep the blood in, but it rushed between my fingers. It just kept coming. I slumped forward and it glugged out like a water fountain.

Everything was a blur. I didn't see the white faces in the crowd. I didn't see fans pass out or any of the players vomiting on the ice. I didn't hear Blues forward Rick Meagher turn to the benches and scream for help. All I saw was the blood rushing into a red sea around me. I'm going to die. Terry Gregson, the referee, looked down at me. His eyes were huge. "Get a stretcher -- he's bleeding to death!"

Everything was a blur. I didn't see the white faces in the crowd. I didn't see fans pass out or any of the players vomiting on the ice. I didn't hear Blues forward Rick Meagher turn to the benches and scream for help. All I saw was the blood rushing into a red sea around me. I'm going to die. Terry Gregson, the referee, looked down at me. His eyes were huge. "Get a stretcher -- he's bleeding to death!"

Our trainer, Jim Pizzutelli, got to me first. He had gauze from the medical kit. He pushed it against my throat, holding me so tight I could barely breathe. The crease was covered in blood. I coughed out, "Jim, it's my jugular."

He was so calm. "Just do what I say."

Years earlier, Jim had been a combat engineer in the Vietnam War. His second week in, he was walking through a village when a truck collided with him and four other soldiers. The impact broke his ribs. It tossed another soldier into a gully, where he was decapitated by a sheet-metal hut. Jim was medevacked out, with the young man's body and head beside him. He studied sports medicine after the war. Now here he was, squeezing his arm around my neck.

"We're going to save you."

"Jim, I can't breathe."

He flexed his grip.

"You’re not going to breathe until we get you to a doctor."

He helped me to my skates and we made it through the doors behind my net. I was scared as hell. I had no idea how much blood I had already lost. I had seen a television show that said a severed jugular would bleed out in minutes. I'm going to die.

He helped me to my skates and we made it through the doors behind my net. I was scared as hell. I had no idea how much blood I had already lost. I had seen a television show that said a severed jugular would bleed out in minutes. I'm going to die.

My mother was at home in Calgary, watching the game on satellite. I couldn't let her see this happen -- not on the ice, not on TV, not like this. They put me on a table in the trainer’s room. Rip Simonick, our equipment manager, stood over me and held my hand. I asked him to call my mom. When I first started playing for the Sabres, I saw a chaplain hanging around the arena. I asked Rip to call for him, figuring God might be my only hope to live. But at the one game I really needed him, the chaplain wasn't there.

One of the team's doctors took a towel and pressed it down on my throat with all his weight. He'd let up so I could breathe, and the blood would spout out and he'd press back down.

I still didn’t have a sense of time. There was mass confusion. Lots of nurses and doctors came down from the stands, wanting to help.

Security had to clear everyone out. Jim started cutting off my pads and chest protector. Rip was still holding my hand as he dialed my mother's number. I didn't want to pass out. If I close my eyes, I won't wake up.

Security had to clear everyone out. Jim started cutting off my pads and chest protector. Rip was still holding my hand as he dialed my mother's number. I didn't want to pass out. If I close my eyes, I won't wake up.

The ambulance seemed to take forever, but it was probably only ten minutes. When it finally arrived, they got me on a stretcher and put an IV in my arm. I tried to make a joke: "Put in a couple stitches and let me get back out there." Blood gurgled out as I said it. No one laughed. They were white as ghosts, and I figured it was the end.

Rip said, "I talked to your mom. She says she loves you."

Our team doctor climbed into the ambulance with the paramedics and pushed down on my neck the whole ride to Buffalo General. They wheeled me through the emergency room doors. I was still wearing my hockey pants and long johns -- they cut the gear off me. They told me I was going to be okay, and I wanted to believe them. I tried to. They put a needle in my arm and I watched their frantic faces drift away.

Back at the Aud, more than fifteen thousand fans, two teams and all the viewers at home still weren’t sure if I would survive. There were reports that two fans suffered heart attacks. At the very least, everyone had witnessed a scene they would never erase from their minds.

The teams left the ice after the accident. The players were terrified. My teammate and close friend Grant Ledyard was freaking out -- he sobbed with his head in his hands in the Sabres' dressing room.

The teams left the ice after the accident. The players were terrified. My teammate and close friend Grant Ledyard was freaking out -- he sobbed with his head in his hands in the Sabres' dressing room.

No one wanted to play after that, but eventually the word came through that I'd live, so the game resumed. The players went back to the benches to finish the first period. My replacement, Jacques Cloutier, stood in the dark red crease and crouched as the puck dropped and the clock started ticking again -- 4:42 ... 4:41 ... He played in a pool of my blood and trembled through the rest of the game.

Before returning to the Sabres' bench, Jim Pizzutelli went to change out of his stained clothes. He pulled off his shoes and realized his socks were soaked with my blood. On the bench, he stared forward blankly as the periods went on and thought about how close I'd been to death. An hour after the game, he sat in the trainer’s office and locked the door. He stayed there alone and refused to talk to anyone.

I woke up famous. Not just NHL-famous, but CNN news cycle–famous. The surgery took only an hour and a half, but by the time the surgeon had woven more than three hundred stitches inside and outside the six-inch gash on the right side of my neck, it seemed like every person in North America had seen the accident.

My sister, Terry, was in the hospital room with me. She drove down from Toronto and must have left right when the collision happened, because she was there within two hours, when I woke up. As I feared, Mom had seen the collision on television, had watched me bleed out until the cameras turned away and the announcer lost his composure.

"Take the ... aww man! That is the ... oh God! Oh, please take the camera off. Don’t even bring it over there. Please. Oh my God. Please take it away. That is terrible. Oh my God, what happened?" Mom saw it all and heard it all. She flipped. My brother, Garth, was at her house when it happened. She called him into the living room. "Something's wrong. Clint's bleeding." He told her not to worry because it was probably just another broken nose. "His nose is always in the way," he said.

Reporters swarmed the hospital. They tried to sneak in, saying they were relatives. A few made it all the way to my room, but we sent the bastards away. The Sabres' physician, Dr. John Butsch, came in and I asked him what the damage was. He was reassuring. "You lost a lot of blood, but you’re out of danger. You're going to be fine." The surgeon closed the veins on the sliced side of my neck. The other side would compensate, Dr. Butsch said. They had to repair the severed tendons and muscle. The gash stopped a millimeter from my internal carotid artery. If the skate had sliced just a bit deeper, it might as well have been a guillotine.

I asked Dr. Butsch when I could get back on the ice. He said he wasn't sure because I'd lost so much blood, but it would likely take a while. Other doctors and physicians came in as well, and they told me a lot of different things. Team management shared their thoughts, too. Everyone had an opinion. Some told me to take the rest of the season off and recover through the playoffs -- "Just take it easy for a couple of months." Some said I should retire. But it didn’t really matter what they said, because I was going to play as soon as I possibly could. A lot of people thought I’d never come back. I didn't even entertain the idea.

The press kept hounding us, so the hospital asked me to do a press conference. The room was packed. My sister was still there. It was just me and her and the hospital's PR staff.

The press kept hounding us, so the hospital asked me to do a press conference. The room was packed. My sister was still there. It was just me and her and the hospital's PR staff.

"When you get knocked off the horse, you get back on," I told the reporters. "It'll be tough to play, but I’ll have to be ready ... I’ll be psyched for it ... I'm anxious to get in there. I'll be happy to play. Something like this kind of opens your eyes. You have a life to live ... I'm lucky to be here."

There was such a demand from the media that we had to do a second press conference later that afternoon. And that’s when I broke down. I don't really know what happened. I wept in front of everyone, with this big bandage on my neck. Earlier, because I was a Sabre, I'd visited with some kids in the cancer ward and posed for pictures and signed autographs. They were so happy and sweet. They were so excited to see me. But it affected me -- I'm alive and going to make it. These kids are still fighting. Some of the kids will die. How scared was I during the accident? And these kids deal with this every day? Everything flooded out at the press conference. I broke down. I didn't care about the cameras or the recorders. Maybe that's when the shock set in. I let it all out and then pulled it all back in.

I was supposed to stay at the hospital for a few days, but I couldn't get any rest. Even after the press conferences, the reporters kept coming. It was a circus, and it was too much for the hospital to handle. I couldn't stay there any longer, so they released me that night. They took me down to the basement and drove me out a secret exit.

Two days after the accident, I was back where it all started. I called Jim Pizzutelli and asked him to open up the Aud for me before everyone arrived. We walked down the hallway I'd stumbled through, dying, less than 48 hours earlier. I went onto the ice and stood in the blue crease. My blood was gone.

"Boy, we're lucky to be here," I said.

"Boy, we're lucky to be here," I said.

"Damn right," Jim said. "And we're back."

It was nice of him to do, and it helped. But that was the extent of any therapy I'd receive.

That night, the Sabres played the Vancouver Canucks. The team asked me to make an appearance for the fans. I didn't want to do it. I felt like a clown. But they pleaded -- told me the people of the city had stood behind me and were concerned. So, during a stoppage in play halfway through the second period, they opened the Zamboni doors. The arena announcer boomed, "Here he is, Clint Malarchuk!" I stepped out. I could have fainted from the standing ovation -- I was so weak. I had to leave. I was shaking. My legs felt like rubber noodles. I could feel the stitches. It was like a pinch, a sting. Both teams tapped their sticks on the ice and against the boards as I waved.

-- Excerpted by permission from A Matter of Inches: How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond by Clint Malarchuk with Dan Robson. Copyright (c) 2014. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Clint Malarchuk on Twitter @cmalarchuk. Follow Dan Robson on Twitter @RobsonDan.