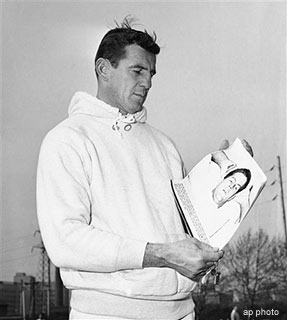

When he left the Philadelphia Daily News to try Hollywood on for size in 1986, John Schulian (b. 1945) assumed he was finished with sportswriting. But sportswriting had a funny way of sneaking back into his life even when he was churning out scripts for such memorable TV series as L.A. Law, Miami Vice, and Wiseguy. He wrote regularly for GQ and Sports Illustrated, just as he had since he came to prominence as a sports columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Daily News in the 1970s. In 1993, before he struck gold as one of the creators of Xena: Warrior Princess, SI asked if he was interested in profiling Chuck Bednarik, the NFL's last full-time two-way player and a symbol of the hearty breed that endured the Depression and World War II. Schulian didn't have to be asked twice. But his enthusiasm didn't convince Bednarik that a mere writer could find his way to his subject’s home in those pre-GPS days. Better they should meet at a large shopping center and proceed from there. The first person Schulian saw when he pulled into the parking lot was a senior citizen with a face like a clenched fist wearing a Philadelphia Eagles jersey and standing in front of a white van, arms the size of Smithfield hams folded across his chest. Bednarik, of course. And he turned out to be a writer's dream: a man without an unexpressed thought.

He went down hard, left in a heap by a crackback block as naked as it was vicious. Pro football was like that in 1960, a gang fight in shoulder pads, its violence devoid of the high-tech veneer it has today. The crackback was legal, and all the Philadelphia Eagles could do about it that Sunday in Cleveland was carry a linebacker named Bob Pellegrini off on his shield.

Buck Shaw, a gentleman coach in this ruffian's pastime, watched for as long as he could, then he started searching the Eagle sideline for someone to throw into the breach. His first choice was already banged up, and after that the standard 38-man NFL roster felt as tight as a hangman's noose. Looking back, you realize that Shaw had only one choice all along.

"Chuck," he said, "get in there."

And Charles Philip Bednarik, who already had a full-time job as Philadelphia's offensive center and a part-time job selling concrete after practice, headed onto the field without a word. Just the way his father had marched off to the open-hearth furnaces at Bethlehem Steel on so many heartless mornings. Just the way Bednarik himself had climbed behind the machine gun in a B-24 for 30 missions as a teenager fighting in World War II. It was a family tradition: Duty called, you answered.

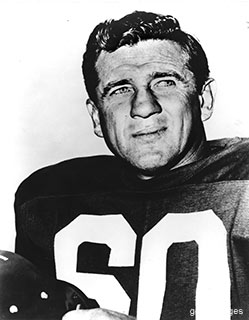

Chuck Bednarik was 35 years old, still imposing at 6'3" and 235 pounds, but also the father of one daughter too many to be what he really had in mind -- retired. Jackie's birth the previous February gave him five children, all girls, and more bills than he thought he could handle without football. So here he was in his 12th NFL season, telling himself he was taking it easy on his creaky legs by playing center after all those years as an All-Pro linebacker. The only time he intended to move back to defense was in practice, when he wanted to work up a little extra sweat.

And now, five games into the season, this: Jim Brown over there in the Cleveland huddle, waiting to trample some fresh meat, and Bednarik trying to decipher the defensive terminology the Eagles had installed in the two years since he was their middle linebacker. Chuck Weber had his old job now, and Bednarik found himself asking what the left outside linebacker was supposed to do on passing plays. "Take the second man out of the backfield," Weber said. That was as fancy as it would get. Everything else would be about putting the wood to Jim Brown.

Bednarik nodded and turned to face a destiny that went far beyond emergency duty at linebacker. He was taking his first step toward a place in NFL history as the kind of player they don't make anymore.

The kids start at about 7 a.m. and don't stop until fatigue slips them a Mickey after dark. For 20 months it has been this way, three grandchildren roaring around like gnats with turbochargers, and Bednarik feeling every one of his years. And hating the feeling. And letting the kids know about it.

Get to be 68 and you deserve to turn the volume on your life as low as you want it. That's what Bednarik thinks, not without justification. But life has been even more unfair to the kids than it has been to him. The girl is eight, the boys are six and five, and they live with Bednarik and his wife in Coopersburg, Pa., because of a marriage gone bad. The kids' mother, Donna, is there too, trying to put her life back together, flinching every time her father’s anger erupts. "I can't help it,” Bednarik says plaintively. “It's the way I am."

The explanation means nothing to the kids warily eyeing this big man with the flattened nose and the gnarled fingers and the faded tattoos on his right arm. He is one more question in a world that seemingly exists to deny them answers. Only with the passage of time will they realize they were yelled at by Concrete Charlie, the toughest Philadelphia Eagle there ever was.

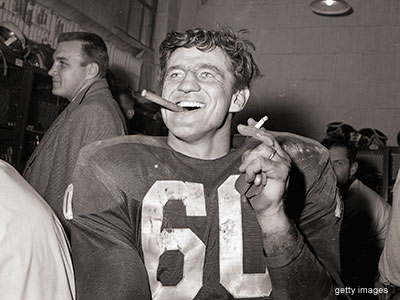

But for the moment, football makes no more sense to the kids than does anything else about their grandfather. "I'm not one of the last 60-minute players," they hear him say. "I am the last.” Then he barks at them to stop making so much noise and to clean up the mess they made in the family room, where trophies, photographs and game balls form a mosaic of the best days of his life. The kids scamper out of sight, years from comprehending the significance of what Bednarik is saying.

He really was the last of a breed. For 58 1⁄2 minutes in the NFL's 1960 championship game, he held his ground in the middle of Philly's Franklin Field, a force of nature determined to postpone the christening of the Green Bay Packers' dynasty. "I didn't run down on kickoffs, that's all," Bednarik says. The rest of that frosty December 26, on both offense and defense, he played with the passion that crested when he wrestled Packers fullback Jim Taylor to the ground one last time and held him there until the final gun punctuated the Eagles’ 17–13 victory.

Philadelphia hasn't ruled pro football since then, and pro football hasn't produced a player with the combination of talent, hunger and opportunity to duplicate what Bednarik did. It is a far different game now, of course, its complexities seeming to increase exponentially every year, but the athletes playing it are so much bigger and faster than Bednarik and his contemporaries that surely someone with the ability to go both ways must dwell among them. It is just as easy to imagine Walter Payton having shifted from running back to safety, or Lawrence Taylor moving from linebacker to tight end. But that day is long past, for the NFL of the '90s is a monument to specialization.

There are running backs who block but don’t run, others who run but only from inside the five-yard line and still others who exist for no other reason than to catch passes. Some linebackers can’t play the run, and some can't play the pass, and there are monsters on the defensive line who dream of decapitating quarterbacks but resemble the Maiden Surprised when they come face mask to face mask with a pulling guard.

“No way in hell any of them can go both ways,” Bednarik insists. "They don’t want to. They’re afraid they'll get hurt. And the money's too big, that's another thing. They'd just say, 'Forget it, I'm already making enough.'"

The sentiment is what you might expect from someone who signed with the Eagles for $10,000 when he left the University of Pennsylvania for the 1949 season and who was pulling down only 17 grand when he made sure they were champions 11 years later. Seventeen grand, and Reggie White fled Philadelphia for Green Bay over the winter for what, $4 million a year? “If he gets that much,” Bednarik says, “I should be in the same class.” But at least White has already proved that some day he will be taking his place alongside Concrete Charlie in the Hall of Fame. At least he isn't a runny-nosed quarterback like Drew Bledsoe, signing a long-term deal for $14.5 million before he has ever taken a snap for the New England Patriots. "When I read about that," Bednarik says, "I wanted to regurgitate."

He nurtures the resentment he is sure every star of his era shares, feeding it with the dollar figures he sees in the sports pages every day, priming it with the memory that his fattest contract with the Eagles paid him $25,000, in 1962, his farewell season.

“People laugh when they hear what I made,” he says. “I tell them, 'Hey, don't laugh at me. I could do everything but eat a football.'" Even when he was in his 50s, brought back by then coach Dick Vermeil to show the struggling Eagles what a champion looked like, Bednarik was something to behold. He walked into training camp, bent over the first ball he saw and whistled a strike back through his legs to a punter unused to such service from the team’s long snappers. "And you know the amazing thing?” Vermeil says. "Chuck didn't look."

He was born for the game, a physical giant among his generation's linebackers, and so versatile that he occasionally got the call to punt and kick off. “This guy was a football athlete,” says Nick Skorich, an Eagle assistant and head coach for six years. “He was a very strong blocker at center and quick as a cat off the ball.” He had to be, because week in, week out he was tangling with Sam Huff or Joe Schmidt, Bill George or Les Richter, the best middle linebackers of the day. Bednarik more than held his own against them, or so we are told, which is the problem with judging the performance of any center. Who the hell knows what's happening in that pile of humanity?

It is different with linebackers. Linebackers are out there in the open for all to see, and that was where Bednarik was always at his best. He could intercept a pass with a single meat hook and tackle with the cold-blooded efficiency of a sniper. “Dick Butkus was the one who manhandled people,” says Tom Brookshier, the loquacious former Eagle cornerback. “Chuck just snapped them down like rag dolls.”

It was a style that left Frank Gifford for dead, and New York seething, in 1960, and it made people everywhere forget that Concrete Charlie, for all his love of collisions, played the game in a way that went beyond the purely physical. "He was probably the most instinctive football player I've ever seen," says Maxie Baughan, a rookie linebacker with the Eagles in Bednarik's whole-schmear season. Bednarik could see a guard inching one foot backward in preparation for a sweep or a tight end setting up just a little farther from the tackle than normal for a pass play. Most important, he could think along with the best coaches in the business.

And the coaches didn't appreciate that, which may explain the rude goodbye that the Dallas Cowboys' Tom Landry tried to give Bednarik in ’62. First the Cowboys ran a trap, pulling a guard and running a back through the hole. "Chuck was standing right there,” Brookshier says. “Almost killed the guy.” Next the Cowboys ran a sweep behind that same pulling guard, only to have Bednarik catch the ballcarrier from behind. "Almost beheaded the guy," Brookshier says. Finally the Cowboys pulled the guard, faked the sweep and threw a screen pass. Bednarik turned it into a two-yard loss. “He had such a sense for the game,” Brookshier says. "You could do all that shifting and put all those men in motion, and Chuck still went right where the ball was."

Three decades later Bednarik is in his family room watching a tape from NFL Films that validates what all the fuss was about. The grandchildren have been shooed off to another part of the house, and he has found the strange peace that comes from seeing himself saying on the TV screen, “All you can think of is 'Kill, kill, kill.'" He laughs about what a ham he was back then, but the footage that follows his admission proves that it was no joke. Bednarik sinks deep in his easy chair. “This movie,” he says, "turns me on even now."

Suddenly the spell is broken by a chorus of voices and a stampede through the kitchen. The grandchildren again, thundering out to the backyard. "Hey, how many times I have to tell you?" Bednarik shouts. “Close the door!"

The pass was behind Gifford. It was a bad delivery under the best of circumstances, life-threatening where he was now, crossing over the middle. But Gifford was too much the pro not to reach back and grab the ball. He tucked it under his arm and turned back in the right direction, all in the same motion -- and then Bednarik hit him like a lifetime supply of bad news.

Thirty-three years later there are still people reeling from the Tackle, none of them named Gifford or Bednarik. In New York somebody always seems to be coming up to old number 16 of the Giants and telling him they were there the day he got starched in the Polo Grounds (it was Yankee Stadium). Other times they

say that everything could have been avoided if Charlie Conerly had thrown the ball where he was supposed to (George Shaw was the guilty Giant quarterback).

And then there was Howard Cosell, who sat beside Gifford on Monday Night Football for 14 years and seemed to bring up Bednarik whenever he was stuck for something to say. One week Cosell would accuse Bednarik of blindsiding Gifford, the next he would blame Bednarik for knocking Gifford out of football. Both were classic examples of telling it like it wasn't.

But it is too late to undo any of the above, for the Tackle has taken on a life of its own. So Gifford plays along by telling what sounds like an apocryphal story about one of his early dates with the woman who would become his third wife. “Kathie Lee,” he told her, “one word you're going to hear a lot of around me is Bednarik.” And Kathie Lee supposedly said, “What's that, a pasta?”

For all the laughing Gifford does when he spins that yarn, there was nothing funny about November 20, 1960, the day Bednarik handed him his lunch. The Eagles, who complemented Concrete Charlie and Hall of Fame quarterback Norm Van Brocklin with a roster full of tough, resourceful John Does, blew into New York intent on knocking the Giants on their media-fed reputation. Philadelphia was leading 17–10 with under two minutes to play, but the Giants kept slashing and pounding, smelling one of those comeback victories that were supposed to be the Eagles’ specialty. Then Gifford caught that pass. "I ran through him right up here,” Bednarik says, slapping himself on the chest hard enough to break something. "Right here." And this time he pops the passenger in his van on the chest. "It was like when you hit a home run; you say, 'Jeez, I didn't even feel it hit the bat.'"

Huff would later call it "the greatest tackle I’ve ever seen," but at the time it happened his emotion was utter despair. Gifford fell backward, the ball flew forward. When Weber pounced on it, Bednarik started dancing as if St. Vitus had taken possession of him. And as he danced, he yelled at Gifford, “This game is over!” But Gifford couldn't hear him.

"He didn't hurt me,” Gifford insists. “When he hit me, I landed on my ass and then my head snapped back. That was what put me out -- the whiplash, not Bednarik."

Whatever the cause, Gifford looked like he was past tense as he lay there motionless. A funereal silence fell over the crowd, and Bednarik rejoiced no more. He has never been given to regret, but in that moment he almost changed his ways. Maybe he actually would have repented if he had been next to the first Mrs. Gifford after her husband had been carried off on a stretcher. She was standing outside the Giants' dressing room when the team physician stuck his head out the door and said, “I’m afraid he's dead." Only after she stopped wobbling did Mrs. Gifford learn that the doctor was talking about a security guard who had suffered a heart attack during the game. Even so, Gifford didn’t get off lightly. He had a concussion that kept him out for the rest of the season and all of 1961. But in ’62 he returned as a flanker and played with honor for three more seasons. He would also have the good grace to invite Bednarik to play golf with him, and he would never, ever whine about the Tackle. “It was perfectly legal,” Gifford says. “If I'd had the chance, I would have done the same thing to Chuck."

But all that came later. In the week after the Tackle, with a Giant-Eagle rematch looming, Gifford got back at Bednarik the only way he could, by refusing to take his calls or to acknowledge the flowers and fruit he sent to the hospital. Naturally there was talk that Gifford's teammates would try to break Concrete Charlie into little pieces, especially since Conerly kept calling him a cheap-shot artist in the papers. But talk was all it turned out to be. The Eagles, on the other hand, didn't run their mouths until after they had whipped the Giants a second time. Bednarik hasn't stopped talking since then.

"This is a true story,” he says. "They're having a charity roast for Gifford in Parsippany, N. J., a couple of years ago, and I'm one of the roasters. I ask the manager of this place if he'll do me a favor. Then, when it's my turn to talk, the lights go down and it's dark for five or six seconds. Nobody knows what the hell's going on until I tell them, 'Now you know how Frank Gifford felt when I hit him.'"

He grew up poor, and poor boys fight the wars for this country. He never thought anything of it back then. All he knew was that every other guy from the south side of Bethlehem, Pa., was in a uniform, and he figured he should be in a uniform too. So he enlisted without finishing his senior year at Liberty High School. It was a special program they had; your mother picked up your diploma while you went off to kill or be killed. Bednarik didn’t take anything with him but the memories of the place he called Betlam until the speech teachers at Penn classed up his pronunciation. Betlam was where his father emigrated from Czechoslovakia and worked all those years in the steel mill without making foreman because he couldn’t read or write English. It was where his mother gave birth to him and his three brothers and two sisters, then shepherded them through the Depression with potato soup and second-hand clothes. It was where he made 90 cents a round caddying at Saucon Valley Country Club and $2 a day toiling on a farm at the foot of South Mountain, and gave every penny to his mother. It was where he fought in the streets and scaled the wall at the old Lehigh University stadium to play until the guards chased him off. “It was,” he says, “the greatest place in the world to be a kid."

The worst place was in the sky over Europe, just him and a bunch of other kids in an Army Air Corps bomber with the Nazis down below trying to incinerate them. "The antiaircraft fire would be all around us,” Bednarik says. "It was so thick you could walk on it. And you could hear it penetrating. Ping! Ping! Ping! Here you are, this wild, dumb kid, you didn't think you were afraid of anything, and now, every time you take off, you’re convinced this is it, you're gonna be ashes."

Thirty times he went through that behind his .50-caliber machine gun.

He still has the pieces of paper on which he neatly wrote each target, each date.

It started with Berlin on August 27, 1944, and ended with Zwiesel on April 20, 1945. He looks at those names now and remembers the base in England that he flew out of, the wake-ups at four o’clock in the morning, the big breakfasts he ate in case one of them turned out to be his last meal, the rain and fog that made just getting off the ground a dance with death. "We'd have to scratch missions because our planes kept banging together,” he says. “These guys were knocking each other off.”

Bednarik almost bought it himself when his plane, crippled by flak, skidded off the runway on landing and crashed. To escape he kicked out a window and jumped 20 feet to the ground. Then he did what he did after every mission, good or bad. He lit a cigarette and headed for the briefing room, where there was always a bottle on the table. “I was 18, 19 years old,” he says, “and I was drinking that damn whiskey straight.”

The passing of time does nothing to help him forget, because the war comes back to him whenever he looks at the tattoo on his right forearm. It isn't like the CPB monogram that adorns his right biceps, a souvenir from a night on some Army town. The tattoo on his forearm shows a flower blossoming to reveal the word mother. He got it in case his plane was shot down and his arm was all that remained of him to identify.

There were only two things the Eagles didn't get from Bednarik in 1960: the color TV and the $1,000 that had been their gifts to him when he said he was retiring at the end of the previous season. The Eagles didn’t ask for them back, and Bednarik didn’t offer to return them. If he ever felt sheepish about it, that ended when he started going both ways.

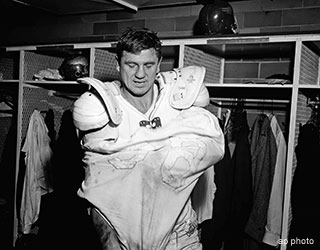

For no player could do more for his team than Bednarik did as pro football began evolving into a game of specialists. He risked old bones that could just as easily have been out of harm's way, and even though he never missed a game that season -- and only three in his entire career -- every step hurt like the dickens.

Bednarik doesn't talk about it, which is surprising because, as Dick Vermeil says, "it usually takes about 20 seconds to find out what’s on Chuck’s mind.” But this is different. This is about the code he lived by as a player, one that treated the mere thought of calling in sick as a betrayal of his manhood. "There's a difference between pain and injury,” Baughan says, “and Chuck showed everybody on our team what it was."

His brave front collapsed in front of only one person, the former Emma Margetich, who married Bednarik in 1948 and went on to reward him with five daughters. It was Emma who pulled him out of bed when he couldn’t make it on his own, who kneaded his aching muscles, who held his hand until he could settle into the hot bath she had drawn for him.

"Why are you doing this?” she kept asking. “They’re not paying you for it.” And every time, his voice little more than a whisper, he would reply, “Because we have to win.” Nobody in Philadelphia felt that need more than Bednarik did, maybe because in the increasingly distant past he had been the town's biggest winner. It started when he took his high school coach’s advice and became the least likely Ivy Leaguer that Penn has ever seen, a hard case who had every opponent he put a dent in screaming for the Quakers to live up to their nickname and de-emphasize football.

Next came the 1949 NFL champion Eagles, with halfback Steve Van Buren and end Pete Pihos lighting the way with their Hall of Fame greatness, and the rookie Bednarik ready to go elsewhere after warming the bench for all of his first two regular-season games. On the train home from a victory in Detroit, he took a deep breath and went to see the head coach, who refused to fly and had one of those names you don't find anymore, Earle (Greasy) Neale. "I told him, ‘Coach Neale, I want to be traded, I want to go somewhere I can play,’ ” Bednarik says. "And after that I started every week -- he had me flip-flopping between center and linebacker -- and I never sat down for the next 14 years."

He got a tie clasp and a $1,100 winner’s share for being part of that championship season, and then it seemed that he would never be treated so royally again. Some years before their return to glory, the Eagles were plug-ugly, others they managed to maintain their dignity, but the team's best always fell short of Bednarik's. From 1950 to ’56 and in '60 he was an All-Pro linebacker.

In the ’54 Pro Bowl he punted in place of the injured Charley Trippi and spent the rest of the game winning the MVP award by recovering three fumbles and running an interception back for a touchdown. But Bednarik did not return to the winner’s circle until Van Brocklin hit town.

As far as everybody else in the league was concerned, when the Los Angeles Rams traded the Dutchman to Philadelphia months before the opening of the '58 season, it just meant one more Eagle with a tainted reputation. Tommy McDonald was being accused of making up his pass patterns as he went along, Brookshier was deemed too slow to play cornerback, and end Pete Retzlaff bore the taint of having been cut twice by Detroit. And now they had Van Brocklin, a long-in-the-tooth quarterback with the disposition of an unfed doberman.

In Philly, however, he was able to do what he hadn't done in L.A. He won.

And winning rendered his personality deficiencies secondary. So McDonald had to take it when Van Brocklin told him that a separated shoulder wasn't reason enough to leave a game, and Brookshier, fearing he had been paralyzed after making a tackle, had to grit his teeth when the Dutchman ordered his carcass dragged off the field. "Actually Van Brocklin was a lot like me,” Bednarik says. “We both had that heavy temperament."

But once you got past Dutch's mouth, he didn't weigh much. The Eagles knew that Van Brocklin wasn't one to stand and fight, having seen him hightail it away from a postgame beef with Pellegrini in Los Angeles. Concrete Charlie, on the other hand, was as two-fisted as they came. He decked a teammate who was clowning around during calisthenics just as readily as he tried to punch the face off a Pittsburgh Steeler guard named Chuck Noll. Somehow, though, Bednarik was even tougher on himself. In '61, for example, he tore his right biceps so terribly that it wound up in a lump by his elbow. "He hardly missed a down," says Skorich, who had ascended to head coach by then, “and I know for a fact he's never let a doctor touch his arm.” That was the kind of man it took to go both ways in an era when the species was all but extinct.

The San Francisco 49ers were reluctant to ask Leo Nomellini to play offensive tackle, preferring that he pour all his energy into defense, and the Giants no longer let Gifford wear himself out at defensive back. In the early days of the American Football League the Kansas City Chiefs had linebacker E. J. Holub double-dipping at center until his ravaged knees put him on offense permanently. But none of them ever carried the load that Bednarik did. When Buck Shaw kept asking him to go both ways, there was a championship riding on it. "Give it up, old man,” Paul Brown said when Bednarik got knocked out of bounds and landed at his feet in that championship season. Bednarik responded by calling the patriarch of the Browns a 10-letter obscenity. Damned if he would give anything up.

-- Excerpted by permission from Football: Great Writing About The National Sport. Edited by John Schulian. Copyright (c) 2014 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc. Published by The Library Of America. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.