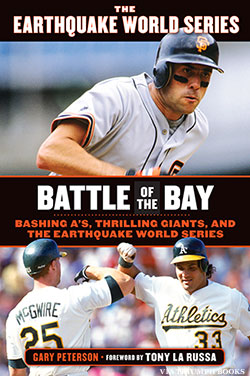

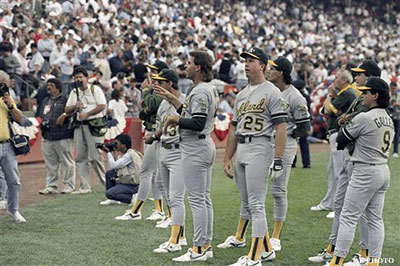

1989 was a season of both triumph and tragedy for the San Francisco Giants and Oakland Athletics, still marking baseball's only cross-Bay series. But 1989 is remembered as much for the devastating earthquake that struck moments before Game 3 of the World Series as it is for the exploits of Mark McGwire, Will Clark, and other stars. In this history, Gary Peterson combines his firsthand observations with meticulous research and new interviews with players, coaches, and broadcasters to offer a fresh perspective of that unforgettable year. Here is an excerpt from Battle of the Bay.

It began as a subtle vibration -- not unlike those caused by commercial airliners as they would pass over Candlestick Park on their ascent from nearby San Francisco International Airport. And briefly -- for less time than it takes to articulate that thought -- that's what I figured it was: an airplane. My second thought was one I'd had on many occasions over the years: This would be a really crummy time for an earthquake.

It wasn't an idle thought. My senior project for U.S. history, my final assignment as a high school student, was a term paper on earthquakes. I learned about P waves and S waves. I learned about the Richter scale, on which every point represents a magnitude order of 10. In other words a 2.0 earthquake isn't twice as powerful as a 1.0 earthquake; it's 10 times as strong. I learned that the next devastating earthquake to ravage the Bay Area was a question of when -- not if. And most frighteningly, I learned that no matter what the building code or what we had learned about engineering over the years, there was nothing man could construct that a sufficiently powerful earthquake couldn't wreck.

My fondest dream was realized when after high school and four years of college, I was hired as a sportswriter by the Valley Times of Pleasanton, California, a part of the Contra Costa Times group. Soon, much sooner than I deserved, I was given a column that gave me an entrée to the full menu of Bay Area sports -- the Giants, A's, 49ers, Raiders, Warriors, Cal, Stanford. I spent a lot of time crossing the Bay Bridge, where traffic sometimes would come to a grinding halt and I would think to myself, This would be a really crummy time for an earthquake.

The same thought occasionally crossed my mind as I sat in a sold-out stadium or traveled an elevated freeway. Now, just minutes before the scheduled start of Game 3 of the 1989 World Series between the A's and Giants, as the subtle vibration began to morph into a gentle bouncing motion, I realized my greatest fear was coming true. There was no plane passing overhead. And even if there was, it wouldn't cause the arrhythmic jostling that was beginning to pitch me back and forth, side to side. This was an earthquake, alright. I had experienced earthquakes before. But this one seemed more insistent and more intense. I was seated in the dreaded auxiliary press box, where they put overflow media at big sporting events (in this case Section 1 in the upper deck at Candlestick Park). I began to bounce up and down.

No, seriously: This would be a really crummy time for an earthquake.

The bouncing intensified. We were beginning to rock and roll. I looked at the football press box, tucked under the canopy of the upper deck on the third-base side of the stadium. I had watched dozens of 49ers games from inside those Spartan quarters. Now its plate glass windows flexed in and out, reflecting funhouse mirror images as they moved. Beginning to panic just a little, I looked out at the second deck beyond center field. We were bouncing to such an extent that it seemed inconceivable that Candlestick Park, the most maligned stadium in sports, could stand the strain. Which part of the inelegant cement bowl would fail first? The light towers swayed like tall stalks of corn. Something had to give. But what? And when? The shaking and jolting went on for what seemed like minutes. And then it stopped.

A half beat later, the crowd let loose with a hearty cheer. Candlestick Park had taken Mother Nature's kick to the gut and was still standing. But I was consumed with dread. With earthquakes you can never be sure. Was what you felt a relatively small quake that seemed bigger than it was because it was epicentered just below your feet? Or was it a powerful event that traveled miles to reach you? I wasn't sure. But I was unsettled.

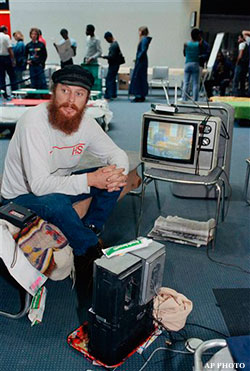

Within minutes, power was out at the stadium. I was armed with a Sony Watchman, a hand-held TV with a screen about half the size of today's smart phones. I had fresh batteries. I turned it on. It took what seemed like forever to locate a signal from one of the local TV stations. When I finally found one, the magnitude of the devastation was beyond what I had imagined. There were no cars in the water beneath the Bay Bridge as had been rumored almost instantly after the shaking stopped. But the bridge was impassable.

It would be long, slow minutes before we found out about the fires in San Francisco's Marina District and the collapse of the Cypress Structure Freeway in Oakland. But even before the official announcement, I was certain of one thing: there would be no baseball that day. It didn't take a genius to figure that out. There was no power at the stadium and a collapsed double-deck freeway just a few miles from where a World Series game was supposed to have been contested. Death. Destruction. The need for police and firefighting resources elsewhere around San Francisco. Clearly, the stadium would need to be inspected.

I began packing my briefcase.

"What are you doing?" asked a colleague.

"They aren't going to play this game," I told him. I made for the nearest ramp to the lower deck. I needed to get out of the stadium and circle around to the players' parking lot where my press credential would allow me access. I knew I would be expected to file a story -- game or no game. The line leading out of the stadium moved slowly. As we shuffled down the ramps, some opportunists were already offering to buy ticket stubs for souvenirs. Occasionally you could feel the slight jostle of another quake.

This would be a really crummy time for a serious aftershock.

I finally made my way to the players' parking lot and began conducting interviews. I'd be lying if I said my heart was in it. The sun was beginning to set. The parking lot looked like an oil painting with thousands of cars sitting motionless with their taillights glowing.

I hooked up with two other colleagues. We needed a place to write. But where? We weren't keen on reentering the stadium and climbing back up to a blacked-out Section 1. We would learn later that some out-of-town reporters wrote their stories in the parking lot by the light of a rental car's headlights -- a semicircle of scribes in a race to finish their stories before the car battery went dead.

I had a better idea. For years Major League Baseball has provided media and assorted VIPs a pregame brunch and postgame buffet at playoff games. They're nicely done. But the postgame buffets don’t account for the hour or two newspaper reporters need to finish and file their stories. This was the third consecutive year I had covered the postseason. I had become accustomed to arriving at the postgame buffet just in time to see the last food table being wheeled out of the room. I didn't even bother bringing my postgame buffet tickets to Candlestick Park for Game 3 of the World Series. I surely would never use them, and my briefcase was cluttered enough as it was.

There would be no Game 3. But the huge tent erected in the Candlestick Park parking lot to host the brunch and buffet might be open, with its generator, tables, and chairs, maybe even food and drink. I suggested to my two colleagues that we head in that direction. I was right. The tent blazed, an oasis of light. Peering inside, we saw plenty of available tables and chairs. We approached the entrance. "Can I see your tickets?” a security guard asked us. My colleagues produced theirs. I informed the guard that I didn’t have my ticket.

"Then you can't come in," he said. I was dumbfounded. "We're not here for a party," I said, not altogether pleasantly. "We're here to work."

"Sorry," he said.

At that moment, one of my colleagues recognized Connie Lurie, wife of Giants owner Bob Lurie, inside the tent. He called to her. She came over, and we explained our situation. "You let these gentlemen inside," she told the security guy. He did. Mrs. Lurie showed us to a table as if seating us at one of San Francisco's finest restaurants. She brought us something to drink. She brought us food and apologized because it was cold. "We have no way to warm it," she said. "We were planning a postgame party, but now we'll have a post-earthquake party." I knew there were horrific scenes playing out all over the Bay Area. At that moment I felt comforted by her simple act of kindness.

We wrote our stories and then had to solve another problem. The tent had no telephones. This was before air cards and wireless Internet access. The Internet itself was in its embryonic stage. We had Radio Shack TRS-80 word processors -- covered wagons compared to the powerful laptops we use today. We needed an actual phone to transmit. And we knew there was only one place to find one: inside Candlestick Park.

It was dark by then. We left the safety of the tent and walked halfway around the outside of the stadium and up an incline so treacherously steep that it was known as Heartbreak Hill in memory of the Candlestick Park patrons who had succumbed to cardiac arrest trying to climb it. Finally, we reached the same open gate I had exited a few hours earlier. There was no one to stop us, so we reluctantly crept back into the murky darkness.

The pay phone banks in that part of the lower-deck concourse -- essentially behind where home plate would be -- were inside big cutouts in the stadium's cement wall. It was pitch black inside those alcoves. This wasn't going to be easy. Here's what transmitting a story entailed: I had to dial a prefix, then the 10-digit number of the computer at our Walnut Creek office. At the tone I had to dial a 16-digit calling card number to pay for the long-distance call. When I heard the familiar squealing tone, I had to place the phone's handpieces into my word processor's acoustical couplers (they looked like rubber suction cups), making sure the earpiece went into the coupler specific to the earpiece and the mouthpiece into the coupler specific to the mouthpiece.

The TRS-80 (we called them "Trash 80s") had a row of function buttons below the display screen. I had to find and push F4, then F3. Then I had to type the name of the document I wished to transmit and hit enter. It didn't transmit at the speed of light. Not being able to see the screen, I had no idea when the transmission was complete. I gave it plenty of time just to be on the safe side. Then I had to call the office -- prefix, 10-digit number, tone, 16-digit number -- to make sure the story had arrived intact. I don't recall how many tries it took me to successfully transmit and verify. More than one would be a safe guess. I do recall that every second inside that black hole was agony.

Eventually, we all filed our stories. Then there was the small matter of how to get home. With the Bay Bridge closed, the quickest way was over the San Mateo Bridge to the south of Candlestick Park. Before reaching the bridge, we heard a radio report that it had been inspected and cleared for traffic. To get on the bridge required driving on a long flyover, a high, elevated connector. I almost couldn't bring myself to do it.

It's difficult to explain to anyone who hasn't been through an earthquake. For a time afterward, sometimes days, you simply don't trust the ground. You can't be sure if it's done shaking or if the worst is over. You just don't know. It seemed as if we were on the flyover for hours. It was a relief to get on the bridge and an even bigger relief to get to the other side. Not long after getting off the bridge, we heard a radio report that it had been closed again for further inspection. Eventually, we made it back to the office. There wasn't much visible damage in the East Bay. I found a few items toppled over at my house when I got home. That was comforting. But anxiety continued to plague me. I simply couldn't settle down. I turned on the news and watched as much of the nonstop earthquake coverage as I could stand. The images conveyed a sense of hell on Earth. It seemed as if things would never be the same again.

I tried to sleep but couldn't. I got up and turned on the TV again for as long as I could stand it. I tried to sleep, again unsuccessfully. The next day on very little sleep, I went into the office. I knew I would be expected to write a column. And I knew just what to write: "As far as I'm concerned, the World Series is over."

-- Excerpted by permission from Battle of the Bay by Gary Peterson. Copyright (c) 2014 by Gary Peterson. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow Gary Peterson on Twitter @garyscribe.