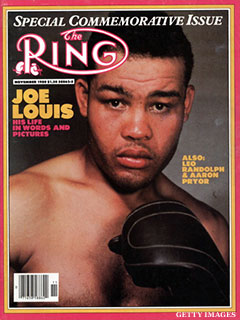

Editor's Note: Joe Louis Barrow was born on May 13, 1914, in Alabama. He moved to Detroit ten years later and began boxing. Louis became the world heavyweight champion in 1937 by defeating James J. Braddock. But it was his bout in 1938 against Germany's Max Schmeling, the only fighter who had ever beaten him, that turned Louis into a national hero. Schmeling was cast as the villain because Nazi propaganda proclaimed him to be an example of Aryan supremacy. Louis won the rematch by knocking out Schmeling in the first round. To help commemorate what would have been his 100th birthday, here is a column by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ira Berkow from his new collection, Counterpunch: Ali, Tyson, The Brown Bomber And Other Stories Of The Boxing Ring. Berkow wrote the column, titled "Louis Had Style In And Out Of The Ring: An Appreciation," in April 1981 shortly after Louis died.

On a cold night in January 1970, three men rode in a cab to Grand Central Terminal, where they would board a train for Rochester. They happened to be going to the same awards dinner. In the back seat were a baseball player and a sports reporter. In the front seat was Joe Louis, the former heavyweight champion, who stared straight ahead as the lurid city lights flashed on his broad face. He listened to the baseball player making cracks about the young cab driver, who had long hair, which was not yet the vogue among athletes.

The ballplayer said something about "hippies" and "sissies," and then about the unusual music playing on the portable radio on the front seat. Louis said nothing.

"Hey," the ballplayer finally said to the cabbie, "turn that damn hippie music off." "That's Greek music," Louis said quietly, speaking for the first time. There was a silence, except for the music. "Oh," the ballplayer said. Joe Louis made his point as deftly, simply, and thoroughly as he had when dispatching opponents in the ring.

Louis died Sunday morning, one month short of his 67th birthday. His death, like his life, moved many people. It was his style as much as his prowess that established Louis as one of the more important figures of his time. "I kept my nose clean," he once said. "And I had to be a gentleman. If I cut the fool, I'd have let my people down."

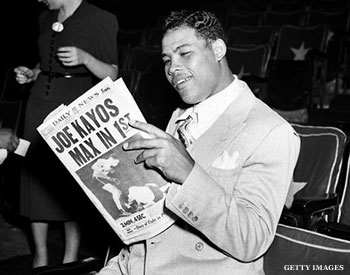

Blacks in America had few heroes to look up to in the 1930s -- in some parts of the United States, blacks still had to get off the streets when the sun went down -- and when Joe Louis won the heavyweight championship of the world by knocking out James J. Braddock June 22, 1937, there was rejoicing.

Walt Frazier, the former Knick basketball star, remembers meeting Louis for the first time. They sat at the coffee shop in Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, where Louis worked as a greeter.

"I had formed an impression of him, from all that I had heard all my life about him," said Frazier. "I was kind of nervous. But he stuck out his hand and said, 'Hiya, Clyde,' like he had known me all his life. Gave me a warm feeling."

Frazier asked him about being a black athlete in the 1930s and 1940s. Louis casually told of not being allowed in some hotels. He told, too, of being in New Orleans when he saw a car hit a black man, of how ambulances from white hospitals wouldn't pick up the man.

In time, though, Louis would be admitted to some of those hotels, and he was instrumental in breaking down other racial barriers. "It’s hard for me to relate to his experiences, because I was too young to remember," Frazier said. "But Joe was a pioneer, like Jackie Robinson. He helped the black man to be proud of himself. He was someone we always looked up to. Black athletes have it so good today. We're reaping what he paved the way for. We should have given him a percentage of our pay."

Louis retired as an undefeated champion in 1949. But in 1950 he decided to try a comeback. Ezzard Charles was the champion. "I didn’t want the fight," Charles would say later. "Joe was my boyhood idol. But my manager, Ray Arcel, said that if I wanted everyone to consider me the champ I’d have to fight Joe. I signed, but I wasn’t happy about it."

Charles dominated the fight. "About the eighth or ninth round," Charles said, "Joe began to falter. I started dreaming, ‘Could this be the great Joe Louis?’ I wanted to win, but I didn’t want to knock him out." Charles won on a 15-round decision.

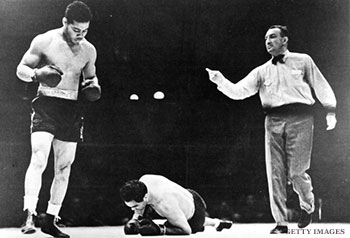

Louis could look back, though, at a remarkable career: He was knocked out by Max Schmeling -- Hitler's Aryan hope -- then came back to knock him out in the first round; he was losing to Billy Conn after 12 rounds and then knocked him out in the 13th.

Another time, he was asked his biggest thrill. "I was able to pay for my sister to go to Howard University," said Louis, who was the son of an Alabama sharecropper and had only a sixth-grade education. "My mother and me went down to Washington for the graduation. The three of us walked across the campus. That was the biggest thrill of my life."

In 1942, at a New York boxing writers dinner, former mayor James J. Walker made a presentation to Louis and, in his flamboyant, sentimental style, said, "Joe Louis, you laid a rose on Abraham Lincoln's grave."

One night in 1968 Louis was again honored by the New York reporters, for his "long and meritorious service" to boxing. He was to receive the James J. Walker Award. Now Louis rose and accepted the plaque.

"Thank you for voting me this James J. Walker Award," he said, in the hushed hall at the Waldorf Astoria. "I think it is a great thing. I remember when he said that I laid a rose on Lincoln’s grave. I didn't know what he meant then. But I knew he was trying to make me feel good. I thought about it later on, and I understood what it was about. Thank you."

-- Excerpted by permission from Counterpunch: Ali, Tyson, the Brown Bomber, and Other Stories of the Boxing Ring by Ira Berkow. Copyright (c) 2014 by Ira Berkow. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.