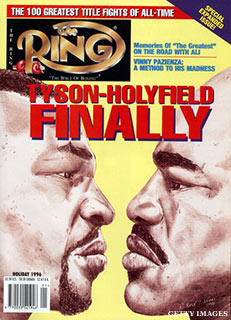

Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield fought twice as professionals, and their second bout produced one of the sport's most bizarre moments. Tyson, who had lost to Holyfield by TKO in their first fight, was disqualified for biting the champion's ear. The seeds to these victories for Holyfield might have been planted many years earlier when both fighters were amateurs trying to make the U.S. Olympic team in 1984. They had two encounters in which Holyfield showed he wasn't going to back down from Tyson, despite his intimidating reputation. This excerpt of The Bite Fight by George Willis reveals how those scenarios unfolded.

The rivalry between the country boy from Georgia and the street thief from Brownsville took root during the lead-up to the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

It was part of Cus D'Amato's master plan for Tyson to win the gold medal and stand atop a podium the way Olympic heroes Muhammad Ali, Floyd Patterson, Joe Frazier, and George Foreman had done in the past.

Olympic Gold would be as valuable as winning a world title as a professional, if not more. The status that came with winning such a prize endured a lifetime.

Sugar Ray Leonard had been the most recent example, capturing the heart of the nation while winning gold at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. He went on to become a world champion and multi-millionaire by the time the '84 Olympics arrived.

D'Amato knew winning the gold on American soil would mean instant celebrity for Tyson, creating the ideal platform from which to launch a lucrative professional career. It was the logical next step in becoming the youngest heavyweight champion in the history of boxing.

This was also the heyday of amateur boxing in the United States, when fighting against international competition and in the Olympics could take a kid like Paul Gonzales from a ghetto in East Los Angeles and allow him to meet five U.S. Presidents and ride in a ticker-tape parade up Broadway in New York City.

This was an era when amateur boxing was a staple of Saturday afternoon television viewing, with Howard Cosell broadcasting from ringside for ABC's Wide World of Sports.

The Los Angeles Games would be the first Olympics for the United States team in eight years, having boycotted the 1980 Games in Moscow. President Jimmy Carter called for the boycott in retaliation after the Soviets sent troops to Afghanistan in December 1979. Fifty-five other countries supported the boycott, denying thousands of amateur athletes their Olympic dreams over a political issue. Twenty-one years after the boycott the United States would launch its own invasion of Afghanistan.

The boycott didn't dull interest in amateur boxing in the United States. That was thanks in large part to the indelible performance of the 1976 U.S. boxing team in Montreal.

There had been singular boxing stars in the previous Olympics: Floyd Patterson winning gold in the 165-pound division in 1952 at Helsinki; Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali) capturing the 178-pound light heavyweight crown at the 1960 Games in Rome; Joe Frazier winning the heavyweight title in 1964 in Tokyo; and George Foreman waving the American flag after claiming gold in the heavyweight division at the historic 1968 Games in Mexico City.

The 1976 group was memorable because it was considered the best team from top to bottom. Howard Davis Jr.; Ray Leonard; Leo Randolph; and the Spinks brothers, Michael and Leon, won a then record five gold medals. Each of the boxers was endearing in their own way: Leonard with his boyish charm, the Spinks brothers with their rugged East St. Louis upbringing, and Davis fighting for gold one week after his 37-year-old mother died of a heart attack.

Inspired by the last words he heard from his mother: "You better bring home the gold medal," Davis won all five of his fights and was voted the Val Barker Award winner as the most outstanding boxer of the tournament.

Leonard would become an instant favorite with his flashy smile and flurry of punches. He punctuated his Olympics with a victory over Cuban knockout-artist Andres Aldama to capture gold. He initially vowed to give up boxing, only to become one of the most popular fighters ever. Each of the Spinks brothers won gold, with Leon defeating Sixto Soria of Cuba and Michael beating Rufat Riskiev of the Soviet Union in their respective finales.

The legacy of the '76 team only heightened expectations for '84. Yet, any notion of duplicating that level of excitement in Los Angeles seemed doomed early on. In retaliation for the Carter-led U.S. boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow, the Soviet Union announced on May 8, 1984, it would boycott the '84 Games. The Cubans and East Germans followed suit.

It eliminated among others, a strong Cuban boxing team that had dominated the 1983 Pan American Games in Caracas, Venezuela, capturing eight gold medals and two silvers.

The U.S. boxers were disappointed. They knew first-hand the Cubans had plenty of talent, having competed against them at the '83 Pan Am Games and various other international tournaments. Unlike the American teams that had to be rebuilt constantly as boxers turned pro, the Cubans remained in their "amateur" programs for multiple Olympics.

Aldofo Horta, the famed featherweight, won gold at the '83 Pan Am Games and also captured silver three years earlier at the '80 Olympics. Pablo Romero, another Cuban, would box on the Cuban amateur team from 1982 to 1989. Included in his record were two gold medals at the World Championships and a victory over Evander Holyfield in the finals of the light heavyweight division in the '83 Pan Am Games.

Emanuel Steward, the late famed-Kronk trainer, worked with several American amateurs in preparation for the '76 and '84 Games. He viewed the Cubans as professional fighters in a sport for amateurs. "They were seasoned guys with 230 fights," Steward said almost three decades later. "That's why I never thought much of them. I thought they were just professional fighters taking advantage of our kids."

Yet, despite the Cubans' success, the '84 U.S. boxers didn't fear them; they were looking forward to competing against them at the Olympics. "Everybody on our team had fought the Cubans and it was back and forth," said Jerry Page, who would make the '84 U.S. team as a 139-pounder. "There was never a dominant situation. With the scene and the atmosphere with the Olympics being in Los Angeles, they would have been in trouble."

Though the Cubans and Russians weren't going to the Olympics, the goals of each of the young American boxers invited to the National Training Center in Colorado Springs that summer didn't change. "We were all there to do the same thing," said Gonzales, the 106-pound light flyweight from East Los Angeles. "We were trying to make the Olympic team. We were all competitive and we were all going for the same goal."

A 17-year-old Tyson and a 21-year-old Holyfield were among those invited to train at the state-of-the-art facility in Colorado Springs. Holyfield earned his invite by capturing a silver medal at the '83 Pan Am Games, while Tyson qualified by winning the 1984 national Golden Gloves championships in St. Louis. That's where the country boy from Georgia and the city kid from Brooklyn met for the first time.

Tyson was in Missouri competing in the heavyweight division, while Holyfield was a light heavyweight. They neither became fast friends or enemies at that tournament. Yet, from the onset there was competitive chemistry between them.

Tyson won all five of his bouts, four by knockout. Holyfield knocked out all five of his opponents, gaining some measure of satisfaction, though Tyson was named "The Outstanding Boxer" of the tournament. It wouldn't be the last time Holyfield obsessed about beating Tyson.

When Holyfield and Tyson arrived at the Training Center in Colorado Springs, they were among the elite amateur boxers in the country, but not necessarily considered the elite of the elite. That level belonged to welterweight Mark Breland of Brooklyn, a five-time national Golden Gloves champion and the sport's most decorated amateur boxer. There was super heavyweight Tyrell Biggs of Philadelphia, who won gold at the 1982 World Championships; Pernell Whitaker, a 132-pounder from Norfolk, Virginia; Frank Tate, a 156-pounder from Detroit; Ricky Womack of Detroit, the favorite in Holyfield's 178-pound light heavyweight division; and the highly touted Gonzales.

The process of making the Olympic Team would be grueling. The boxers were to spend six weeks in Colorado Springs with the Olympic trials set for June 1984 in Fort Worth, Texas. Following the trials, the final roster would be determined by a box-off a few weeks later in Las Vegas. The divisions were so competitive, only Breland seemed to be a sure thing.

"Only 12 guys would make the Olympic team, but there were about 60 guys who could have made it," said Page, who entered the trials as a virtual unknown 139-pounder from Detroit. "That's how competitive the amateur boxing program was back then. There were so many guys that were capable. Guys like Mike Tyson."

Steward was in his heyday as the founder of Kronk Gym in Detroit and working with Tate, Briggs, Tillman, Womack, and Breland. He recalled Cus D'Amato wanting Tyson to compete in the super heavyweight division where his speed would overpower the heavier boxers. But D'Amato had no pull with the U.S. Olympic Committee, who preferred the more experienced Biggs, who won gold two years earlier at the World Championships in Munich and a bronze at the '83 Pan Am Games. Tyson would compete as a 201-pound heavyweight.

D'Amato, along with future co-managers Jimmy Jacobs and Bill Cayton, viewed the trials as a formality for Tyson. He was already one of the most feared amateurs in the nation. On August 12, 1983, four days before the 1983 U.S. National Championship, Tyson had destroyed his first two opponents by knockout. The first was beaten in the first round, while his next opponent was hit so hard in the second round he was unconscious for nearly 10 minutes. His opposition for the finals claimed he had an injury and didn't show up for the fight. "As he progressed, people were so intimidated by him until it was ridiculous," Breland recalled. "They were scared to death."

By the time Tyson got to Colorado Springs there was plenty of curiosity about the hard-punching knockout machine from New York who had a man's body and child-like voice. He was already different from the others because he had a professional management team in place with Jacobs and Cayton ready to take over as managers. Using what D'Amato taught him and refined by Teddy Atlas and then Kevin Rooney, Tyson already had a pro style, where punches were thrown not to score points, but do damage.

But his reputation hardly intimidated the other would-be Olympians in camp. Tyson might have come from the tough streets of Brownsville, Brooklyn, and he might have been built like a small tank, but Gonzales was a gang member in an East L.A. barrio by the age of eight; Tillman was a one-time gang member from Compton, California; Page grew up in the worst ghetto in Columbus, Ohio; and Womack was from the tough streets of Detroit.

Several of the fighters had already met Tyson, including Gonzales, who was impressed Tyson knew his boxing background. "The guy knew my story," Gonzales said. "He knew my ranking. He knew all about my boxing and what I'd done as an amateur. So I took him down the street and bought him an ice cream."

No one paid homage to Tyson. Respect had to be earned. "At that stage you hear about different guys, but because of your own mentality and your own swag, you're not really about being a fan of anybody," Page said.

Tyson kept to himself mostly, as did Holyfield, who wasn't always easy to read. Most of the fighters had come from tough urban cities, East L.A., Philadelphia, Detroit, Brooklyn, places like that. Holyfield was from the South, though no one was eager to test him because of the snarl that seemed permanently etched on his face. It was the kind of look that put others on the defensive, unsure whether Holyfield was simply in a bad mood or looking for conflict.

"He always had this look like he wanted to fight," Gonzales said. "I remember Pernell looked at him and said, ‘I don't know if I should smile at you or fight you.' He's just looking at you with his eyes and just staring right through you. You would assume that he wants to fight you. But that's just the way Holy is."

Sometimes the snarl wasn't meant to be friendly. Having that many fighters housed together for that long of a time was a recipe for some intense showdowns. Two of the most memorable involved Tyson and Holyfield.

The first occurred when Pat Nappi, the head coach of the U.S. Olympic Boxing team, wanted someone to spar with Tyson, who was brutalizing his other sparring partners. Though competing in a lower weight class, Holyfield volunteered.

According to onlookers, their battle was so ferocious Nappi had to stop the sparring after the first round. Twelve years later, as Holyfield prepared to face Tyson for the first time as a pro, he would refer back to that sparring session, telling a confidant: "I whooped his ass. He ain't ever forgot that and I ain't ever forgot that."

Tyson doesn't recall much from the sparring session, only that "I think he hurt his arm. He wasn't feeling well."

Their second showdown wasn't physical, but just as intense. It happened over a pool table. Tyson had control of the table until he scratched while trying to make the eight ball. He wasn't happy, believing that he hadn't really lost the match. Tyson was reluctant to yield to the next player: Holyfield.

Holding a cue stick, Tyson dug out the cue ball and stood as if he wasn't going anywhere. That prompted Holyfield to grab his own cue stick and stare at Tyson with the Holyfield snarl.

The stand-off may have lasted five seconds, but it seemed like five minutes of not knowing whether the two chiseled athletes were going to brawl right then and there. "F--- it," Tyson said, throwing his cue stick and the cue ball on the table before heading back to his room.

To this day, Tyson says he has no recollection of their showdown over a pool table. "I don't know nothing about that," he said. But Holyfield felt he'd scored a huge psychological victory. "I'm not scared of him and he knows I'm not scared of him," Holyfield said to himself. Even then, Holyfield was confident he could take Tyson in the ring.

-- Excerpted by permission from The Bite Fight by George Willis. Copyright (c) 2013 by George Willis. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes. Follow George Willis on Twitter @NYPost_Willis.